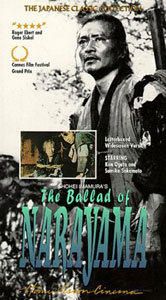

Shohei Imamura's Ballad of Narayama (Narayama bushiko, 1984) is an adaptation of a short story by Shichiro Fukazawa, the story based on a folk legend. This film deservedly won the Cannes Film Festival Golden Palm.

Shohei Imamura's Ballad of Narayama (Narayama bushiko, 1984) is an adaptation of a short story by Shichiro Fukazawa, the story based on a folk legend. This film deservedly won the Cannes Film Festival Golden Palm.

One of the first images we have is of a newborn infant abandoned & dead in a muddy field. There is annoyance among villagers at the intrusion of so small a corpse, but no one feels the need to find out who killed her child.

Infanticide is normal for these people, & the only thing untoward is that the remains were left in a neighbor's field.

The story regards the last days of the aging Orin (Sumiko Sakamoto) who despite her good health & strong teeth tells her son (Ken Ogata) she has now reached that age when it is time to be taken to the throwing-old-people-away place atop Mount Nara, to be discarded before she becomes a burden on her family.

This may or may not actually have been just such a tradition at some point in ancient Japan -- more likely not -- but in a culture that hugely values filiel piety it is certainly a powerful idea that aging parents could be discarded in a chilly mountain location to die of exposure. This may or may not actually have been just such a tradition at some point in ancient Japan -- more likely not -- but in a culture that hugely values filiel piety it is certainly a powerful idea that aging parents could be discarded in a chilly mountain location to die of exposure.

It is perhaps even sometimes a fantasy of guilty pleasure of escaping one's lifelong obligations toward aging parents & grandparents.

Set in a timeless rural region untouched by the swift modernization of the Meiji Era, life is harsh particularly in winter, & village traditions are equally harsh in response.

In Shoei Imamura's view of primitivism & being close to nature, nature is equated with filth. Thus all the villagers seriously need their clothes repaired, & they need baths.

To scrape by, people must be harsh to their very cores. An entire family is buried alive when Amaya (Akio Yokoyama) & his daughter Matsu-yan (Junko Takada) are caught stealing limited resources. Just as brutally in the village's tradition, the elderly are thought undeserving of a portion of rare winter provisions.

In a world where many would die but for the sacrifice of a few, such callousnous is just about credible, though the relentless dirtiness I found harder to believe. In a world where many would die but for the sacrifice of a few, such callousnous is just about credible, though the relentless dirtiness I found harder to believe.

Here is a people for whom suicide, self-sacrifice, murder & capital punishment are blended into indistinguishable acts taken as moral & proper even though unfortunate.

Their human world is as sensual & as violently grotesque as the animal world, where there is no actual cruelty but only a natural balance of mating & birthing, slaying or dying.

Small, often grotesque occurrences decorate the deliberately paced epic-length film. The abject beauty of the village & the forest is contrasted to such strange human behavior as having sex with a dog. Small, often grotesque occurrences decorate the deliberately paced epic-length film. The abject beauty of the village & the forest is contrasted to such strange human behavior as having sex with a dog.

Tatsuhei loves his mother to distraction & is horrified by the decision she has made. He makes every possible excuse not to discard her, explaining her value to him & pointing out how healthy she is. Orin to convince him she is not all that healthy attempts to bash her own teeth out with a rock.

Other story points weave in & out of the narrative involving other villagers. The most amusing & oddly sweet story involves Risuke (Tonpei Hidari), a yalko or younger brother such is not permitted to marry, inherit, or, apparently, bathe. He is for all practical purposes a slave, & famous for his bad odor. Unless the dog counts, he's still a virgin because of his stench.

Oei (Mitsuko Baisho, best known as Tora-san's sister in the long-running Tora-san film series) is supposed to spend one night with each yalko to atone for a crime in her household.

She has slept with each one except Risuke, & refuses to do so because of his odor. Out of pity for his younger brother, Tatsuhei tries to convince his wife (Aki Takejo) to sleep with Risuke one time only, but she too refuses due to the stink.

At last Orin intercedes & convinces a friend her own age, Okane (Nijiko Kyokawa), to sleep with Risuke, as Okane has no sense of smell. At last Orin intercedes & convinces a friend her own age, Okane (Nijiko Kyokawa), to sleep with Risuke, as Okane has no sense of smell.

Okane has long been widowed, but figures her old vagina probably works okay. Thus at last young Risuke learns what it is like to have sex with a woman, & he & old Okane fall fast in love.

Eventually Tatsuhei in obedience to his mother straps a rustic firewood-cradle to his back & Orin sits in it so that her son can carry her to the discarding place of Mount Nara. As her last act for the family, she takes her son's strapping wife Tamayan (Aki Takejo) into the higher forest to teach her some long held secrets of survival, such as a point in a stream where fish always lurk.

Carrying one's elderly parent on one's back symbolizes before the Mountain God the hardships of mountain life, & Orin is to be an offering to the Nara divinity.

Along the way Orin appreciates the beauty around her. Another son with an aged mother is encountered along the same path, with the mother screaming & begging not to be discarded & her son eager to be rid of her. Along the way Orin appreciates the beauty around her. Another son with an aged mother is encountered along the same path, with the mother screaming & begging not to be discarded & her son eager to be rid of her.

But for Orin it is an event with eerie dignity, & she faces the end of life without trepidation, believing deeply in her village's traditions & in the good that will result for her family.

She is left alone in a mountain clearing of corpses & bones, sitting peacefully as a bodhisattva, awaiting a death that is apt to take quite some while, while new snowfall begins to fall upon her.

There is poetry & strangeness to Ballad of Narayama that places it far outside the bounds of modern morality, but which provides much to think about from the perspective of our own cultural assumptions of life & death, right & wrong.

The same tale had earlier been adapted to the screen by Keisuke Kinoshita. This earlier Ballad of Narayama (Narayama bushiko, 1958) is gorgeously filmed in heightened color realer than real. The same tale had earlier been adapted to the screen by Keisuke Kinoshita. This earlier Ballad of Narayama (Narayama bushiko, 1958) is gorgeously filmed in heightened color realer than real.

Kinoshita chose to give the presentation a fabular kabukiesque artificiality with shamisen accompaniment (composed by Matsunosuke Nozawa).

It received Kinema Jumpo Awards for best film, best directors, & best actress. The story has much less reality than in Imamura's widescreen version & of course lacks the erotic component of the later film.

But it's easily the equal of the remake, with a unique enough aesthetic that the two versions could be watched back-to-back with very different impacts on the senses & emotions, very distinct works of art.

The setting is timeless, a traditional village perhaps fifty years ago, a hundred years ago, a thousand years ago. The setting is timeless, a traditional village perhaps fifty years ago, a hundred years ago, a thousand years ago.

Kinuyo Tanaka as elderly Orin & Teiji Takahashi as her griefstricken son who must assist the "throwing away old people" ritual, give a heightened beauty to their circumstance.

This film has been celebrated as an intellectual investigation of "cultural relativism," but for me, it is simply a gorgeously ghastly folk tale.

It's clear that she is not a burden on the family, as she has skills these mountain people benefit by, so tradition is more in play than is any troubling necessity. It's clear that she is not a burden on the family, as she has skills these mountain people benefit by, so tradition is more in play than is any troubling necessity.

Kinoshita's theatric distancing & unreality of the material, together with a higher degree of Romanticism, helps underscore the allegorical significance of Orin's "choice" of death, a choice none of us ultimately can refuse to select.

Ironically, by presenting the tale with less realism, Orin's experience becomes universal rather than culturally specific or exotic. The result is if possible even more lyrical than Imamura's film, in a completely different tempo.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

This may or may not actually have been just such a tradition at some point in ancient Japan -- more likely not -- but in a culture that hugely values filiel piety it is certainly a powerful idea that aging parents could be discarded in a chilly mountain location to die of exposure.

This may or may not actually have been just such a tradition at some point in ancient Japan -- more likely not -- but in a culture that hugely values filiel piety it is certainly a powerful idea that aging parents could be discarded in a chilly mountain location to die of exposure. In a world where many would die but for the sacrifice of a few, such callousnous is just about credible, though the relentless dirtiness I found harder to believe.

In a world where many would die but for the sacrifice of a few, such callousnous is just about credible, though the relentless dirtiness I found harder to believe. Small, often grotesque occurrences decorate the deliberately paced epic-length film. The abject beauty of the village & the forest is contrasted to such strange human behavior as having sex with a dog.

Small, often grotesque occurrences decorate the deliberately paced epic-length film. The abject beauty of the village & the forest is contrasted to such strange human behavior as having sex with a dog. At last Orin intercedes & convinces a friend her own age, Okane (Nijiko Kyokawa), to sleep with Risuke, as Okane has no sense of smell.

At last Orin intercedes & convinces a friend her own age, Okane (Nijiko Kyokawa), to sleep with Risuke, as Okane has no sense of smell. Along the way Orin appreciates the beauty around her. Another son with an aged mother is encountered along the same path, with the mother screaming & begging not to be discarded & her son eager to be rid of her.

Along the way Orin appreciates the beauty around her. Another son with an aged mother is encountered along the same path, with the mother screaming & begging not to be discarded & her son eager to be rid of her.

The setting is timeless, a traditional village perhaps fifty years ago, a hundred years ago, a thousand years ago.

The setting is timeless, a traditional village perhaps fifty years ago, a hundred years ago, a thousand years ago. It's clear that she is not a burden on the family, as she has skills these mountain people benefit by, so tradition is more in play than is any troubling necessity.

It's clear that she is not a burden on the family, as she has skills these mountain people benefit by, so tradition is more in play than is any troubling necessity.