Yakuza-eiga or Japanese gangster films had their heyday from approximately 1964-1974, but were popular in different forms at various times in the history of Japanese cinema. During the Occupation, when samurai films were repressed by MacArthur, the public's thirst for violence was quenched by post-feudal settings of gang warfare, of which Kon Ichikawa's Sanshiro of Ginza (Ginza Sanshiro, Shin Toho, 1950) is the culminating example. The hero is a physician versed in judo techniques which come in handy to do battle against evil gangsters. But many of the earlier gangster films, patterned somewhat on the Hollywood types, had more to do with gunplay than martial arts.

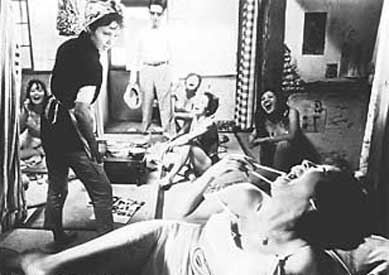

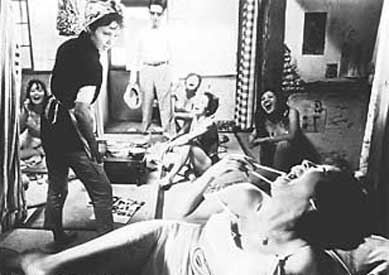

When MacArthur left & period films returned with a passion, gangster films continued to flourish on a less intense level during the following decade, especially at Toei which made wide-screen black & white yakuza-eiga all through the 1950s. But the genre did not immediately hit upon the sort of yakuza-eiga which ends in exhausting, bloody swordplay. In 1961, guns were still more common than swords, as in Shohei Imamura's Pigs & Battleships aka The Flesh is Hot (Buta to Gonkan, Nikkatsu; the still at the right is from this film), ending with a bizarre shoot-out & murderous pig stampede. When MacArthur left & period films returned with a passion, gangster films continued to flourish on a less intense level during the following decade, especially at Toei which made wide-screen black & white yakuza-eiga all through the 1950s. But the genre did not immediately hit upon the sort of yakuza-eiga which ends in exhausting, bloody swordplay. In 1961, guns were still more common than swords, as in Shohei Imamura's Pigs & Battleships aka The Flesh is Hot (Buta to Gonkan, Nikkatsu; the still at the right is from this film), ending with a bizarre shoot-out & murderous pig stampede.

Pigs more resembles & unusually harsh & ugly version of film noirs than it does what would become classical yakuza-eiga. Chases through spookily lit alleys in contrast to the gaudily lit neon jungle of the city, nihilistic anti-heros or no heros at all, set in a lawless world of violence, pornography, prostitution, black markets, & all-round criminality & greed, with moments of decency & the possibility of love squashed by the chaotic post-war environment of every dog (or pig) for himself. The film is either too early, or Imamura too serious & dark a satirist, to romanticize the dark underworld of criminals as occurs in classic yakuza-eiga wherein at least one chivalrous gambler retains feudalistic ideals. Imamura's window into the gangster world is almost too real & too painful, though not without a certain grimy beauty void of romanticism.

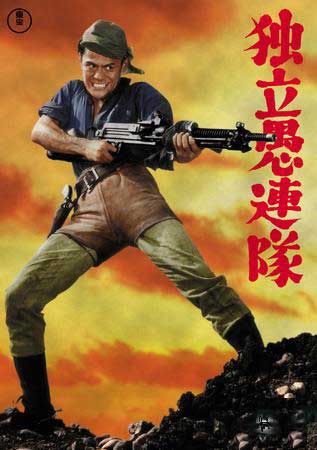

Wartime gangsters were the focus of such films as Kihachi Okamoto's two-part epic Free-Agent Hoodlums aka Desparate Outpost (Dokuritsu Gurentai, Toho, 1959); & Westward Desparado (Dokuritsu Gurentai Nishi-e, Toho, 1960.) The illustration at the top of the page advertises the first part of this double film.

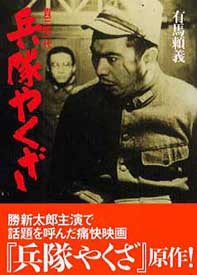

The wartime gangster might be a mercenary hero whose previous experience as a streetfighter makes him an exceptional if unmanageable soldier, as in Dokuritsu Gurentai, or he might be a misfit clever enough to escape the military system & serve himself. In Yasuzo Masamura's Hoodlum Soldier aka Yakuza Hoodlum (Heitai Yakuza, Daiei, 1965; illustration for this film is here at the left) the hero, Kisaburo, is played by Shintaro Katsu of Zatoichi fame. He deserts the army & gets away with it. The wartime gangster might be a mercenary hero whose previous experience as a streetfighter makes him an exceptional if unmanageable soldier, as in Dokuritsu Gurentai, or he might be a misfit clever enough to escape the military system & serve himself. In Yasuzo Masamura's Hoodlum Soldier aka Yakuza Hoodlum (Heitai Yakuza, Daiei, 1965; illustration for this film is here at the left) the hero, Kisaburo, is played by Shintaro Katsu of Zatoichi fame. He deserts the army & gets away with it.

Tokuzo Tanaka directed six Heitai Yakuza sequels between 1966 & 1968. Kazuo Mori directed one in 1966, & Yasuzo Masamura returned to the series in 1972 for a final episode (the only one in color).

In episode after episode they adventure around China perpetuating scams while evading army service. The series just about sweeps clear across the period when yakuza-eiga dominated in the cinemas. Most of these episodes amount to wartime buddy-flicks about the Gangster & the Pacifist (Takahiro Tamura) & did not really coopt the standard yakuza-eiga attitudes that arose in the 1960s. The classic type yakuza-eiga ends in spectacular swordplay for a chivalrous cause, in an ironic way upholding feudal/samurai ideals. The Heitai Yakuza shows charming, witty characters in active revolt against the last military vestages of feudalism in Japan.

Just about the first gangster films to focus on martial arts & swordplay in lieu of the gun involved the concept of the "gangster priest." The pre-eminant yakuza priest film was The Blind Monk Swordsman (Akubozu Kyokaku-den, Toei, 1962), set in the Meiji era, a period of westernization.

This film has as its chief antagonist a man called Death (Chiyonosuke Azuma), dressed in western garb, carrying his sword in a British walking cane. He's nearly as heroic as the blind monk, Tessen, but Tessen's also symbolic of the demise of Japan's traditional ways & feudalism. Though Death symbolizes the new ways & Tessen the old, neither is actually a bad man, much as in Wakayama's Karate Killer Priest series, his nemesis the blind bullwhip priest is not actually evil. We discover in flashbacks that the semi-heroic Death lost his beloved & became a bitter man, his motivations are no more or less grim than Tessen's.

Such yakuza priest films were among the first to sentimentalize the loss of feudalism & to do away with gunplay in favor of swordfights. Wandering priests were living anachronisms in modernizing Japan, carrying illegal swords in pilgrim's staffs & expert in kempo temple boxing.

In the wake of Blind Monk Swordsman more & more gangster films, whether set in the 1920s, during the war, or after the war, built on the idea that the samurai-like feudal pecking order within the yakuza world was nostalgic & wonderful, & even the horror & death criminality added up to was akin to the old samurai willingness to die for a lord. This nostalgic romanticization was deeply needed after the War, when the Emperor was no longer God & the philosophical underpinning of Japanese society had eroded.

But during the 1970s this romanticization began to wear thin, when the "documentary style" yakuza films arose, lacking the chivalrous central protagonist & being more about mayhem for the sake of mayhem. For a typical "documentary style" series, see the overview of Kinji Fukasaku's five-film Yakuza Papers.

Shintaro Katsu & Tomisaburo Wakayama each had their own yakuza priest series, Wakayama's series overlapping with films about a blind priest who fought with bullwhip played by Bunta Sugawara. Bunta's blind priest is to Wakayama's Karate Priest what Death is to the monk Tessen, not the true villain of the piece, but a frightening equal, a worthy opponent.

But Jushiro Konoe's blind monk Tessen was among the earliest & best of this type. Konoe began his film career in the silent era & reached a peak of his popularity in the 1930s, but was still a popular actor near the end of his life in a long-running television series called Samurai Vagabond until diabetes forced his retirement. He has never been well known in the west, not even by die-hard samurai film buffs, though he deserves more recognition. The best chance to see him presently is as a samurai in Zatoichi Challenged (Zatoichi chikemuri kaido, 1967), playing an heroic rather than vile opponent of blind Zatoichi.

Confronted by a number of yakuza flunkies who say to the blind priest, "We're here to revenge our boss!" Tessen wisecracks, "Want to die like him?" And they do. In another humorous scene, he defeats everyone in a martial arts tournament in order to win a small cash prize, ridiculing each opponent by explaining beforehand why each will lose. "If you breathe heavy like that, you can't win." "You are not calm enough. How can you expect to defeat me?"

Angering the discredited school, Tessen is chased through the film by irked samurai (on the cusp of losing their privilege to carry swords at all) as well as yakuza. All the while he himself seeks the yakuza underling Ando, who had blinded him seven years before.

Like Shintaro Katsu in the Zatoichi films, Konoe had superb comic timing but was still easily taken seriously as a deadly swordsmaster. Excellent pacing for fight after well-staged fight, wisecracking as he kills: "Now it's dark. I can't lose!" Also like Zatoichi, Tessen can become totally grotesque in the needed moment, as when he gruffly warns Ando, "I have come for you from Hell!" just before blinding Ando who then begs for mercy. Tessen tells him, "You will feel the pain of darkness" & begins his monk's chanting, & Ando draws his sword.

Supporting cast in the film includes Haruo Tanaka, Shinobu Chibara, Masao Mishima, Kenjiro Uemura, Kusuo Abe & the actress Kikuko Hojo in a double role. A 35 mm subtitled print exists, but has not been shown for years. It is high time this film was ferretted out of its vaults in Japan & re-subtitled for a sharp fine DVD pressing, as it is influential not only for the yakuza priest films that followed, but for the entire yakuza genre which ceased to be so much about gunplay after the initial success of the unjustfly forgotten The Blind Monk Swordsman.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

When MacArthur left & period films returned with a passion, gangster films continued to flourish on a less intense level during the following decade, especially at Toei which made wide-screen black & white yakuza-eiga all through the 1950s. But the genre did not immediately hit upon the sort of yakuza-eiga which ends in exhausting, bloody swordplay. In 1961, guns were still more common than swords, as in Shohei Imamura's Pigs & Battleships aka The Flesh is Hot (Buta to Gonkan, Nikkatsu; the still at the right is from this film), ending with a bizarre shoot-out & murderous pig stampede.

When MacArthur left & period films returned with a passion, gangster films continued to flourish on a less intense level during the following decade, especially at Toei which made wide-screen black & white yakuza-eiga all through the 1950s. But the genre did not immediately hit upon the sort of yakuza-eiga which ends in exhausting, bloody swordplay. In 1961, guns were still more common than swords, as in Shohei Imamura's Pigs & Battleships aka The Flesh is Hot (Buta to Gonkan, Nikkatsu; the still at the right is from this film), ending with a bizarre shoot-out & murderous pig stampede.