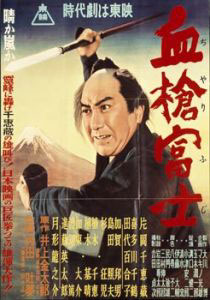

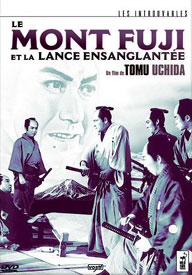

A thorough-going classic of the golden age of the samurai film, Tomu Uchida's A Bloody Spear on Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji, 1955) has beautiful black & white cinematography & a naturalness of acting that pulls you right into the lives of characters.

A thorough-going classic of the golden age of the samurai film, Tomu Uchida's A Bloody Spear on Mount Fuji (Chiyari Fuji, 1955) has beautiful black & white cinematography & a naturalness of acting that pulls you right into the lives of characters.

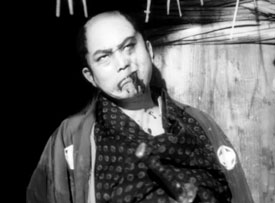

Chiezo Kataoka had been a major light of Japan's silent & early sound cinema, specializing in period films of heroic swordsmen, whether samurai or wandering peasants. He was particularly good at the latter & may have been Japan's first superstar to represent such strong peasant figures rather than the usual bushi class warrior.

But with the arrival of MacArthur's Occupation, period films were banned for having promoted martial spirit. That was pretty much it for Chiezo's career until MacArthur left. As soon as his foot was off the neck of the studios, there was rebirth of samurai drama, but it did not purely glamorize martial spirit. It was the birth of "cruel jidai geki" in which good men suffer or die, and even triumphs are bitter.

Enter Tomu Uchida, a great director critical of how the Japanese government & military had behaved during the Manchurian & Pacific wars. Enter Tomu Uchida, a great director critical of how the Japanese government & military had behaved during the Manchurian & Pacific wars.

Assisting him was, among others, Daisuke Ito, who had written or directed Chiezo's best roles before the war, and had always been a left-tending storyteller who commonly saw pity & injustice in the ways of the samurai.

During the war, directors risked being sent to the war front to die if they displeased the military, & both Uchida & Ito had lost close friends, increasing their antiwar sentiments.

Which is not to say Chiyari Fuji is at all didactic. It has a powerful nostalgia for samurai days, but acknowledges the tragedy of warrior-ruled society. It has national pride all through it, but not of the type that lauds crazed thoughtless patriotism.

Chiezo was getting a mite long in the tooth to play the hero type, but in fact the character of Gonpachi is against type. Chiezo was perfectly cast as a rather commonplace senior vassal whose job is hardly more than that of spear-carrier, nothing great, but he takes pride in it.

Constructed as a "road movie," in Chiyari Fuji Chiezo Kataoka plays his spear-carrier as a good-natured vassal of a minor rural lord, Kojuro (Eijiro Kataoka).

Constructed as a "road movie," in Chiyari Fuji Chiezo Kataoka plays his spear-carrier as a good-natured vassal of a minor rural lord, Kojuro (Eijiro Kataoka).

Having injured his foot along the road, the spearman is intent on his simple duty, limping along holding the spear upright in a ceremonial fashion. He is deeply moved when his master gives him a salve & permits him to rest on the roadside.

While dressing his foot, Gonpachi meets, gruffly & unwillingly, an intrusive, wandering little orphan named Jiro, who soon wins him over. He even lets the boy carry the spear. The relationship with Jiro provides one tiny plot-thread in the elaborately woven story, lasting to the very end, & provides at the center point of the film what amounts to a fart joke, probably to stand forever as the best fart joke ever in a samurai film.

Many great characters populate the tale, including among others a wandering shamisen player with a little daughter (a charmer played by Chiezo's daughter Chie Ueki); & the boy who admires the spearman (who is Chiezo's son Motoharu Ueki).

Others are the nervous traveller Tozaburo (Ryunosuke Tsukigata) whose nerves are due to transporting money; Otane (Yuriko Tashiro), the girl sold into servitude by her weepy father, Yomusaku; the young Lord Kojuro Sakawa who seriously shouldn't drink; & the lord's retainers Genta (Daisuke Kato) & Gonpachi, the latter our hero.

Tales of these sundry figures sweetly intersect, with many subtlties of character & event, all the while conveying a world of tremendous appeal. Tales of these sundry figures sweetly intersect, with many subtlties of character & event, all the while conveying a world of tremendous appeal.

It's a window into ordinary rather than exceptional warrior class behavior in a time of peace, A Bloody Spear on Mount Fuji will not turn grim until the climax, focusing in the meantime on a blend of humor & drama.

Genta & Gonpachi are the only attendants with their lord, on their way to Edo where their master is to meet with his mother. She has instructed the two vassals not to allow her son to drink along the way. He's a good man but becomes very different when drunk.

Among the sundry events on this journey, there's a tattooed thief, Rukuemon, by luck captured by the Gonpachi. Some self-important official magistrates are supposed to provide a reward for the capture of Rukuemon, which young Lord Sakawa plans to turn it over to some needy commoners for whom he feels compassion. But the "reward" turns out to be a pompous, officious letter of thanks, with the cash reward evidently kept by these haughty samurai officials.

This is the event that inspires Sakawa to begin drinking. And though Genta & Gonpachi have been charged with preventing it, the reality is a servant cannot order his master about.

Tozaburo arrives to redeem his daughter Oshina after five years of laboring in a mine, with the one intent of saving her. Tozaburo arrives to redeem his daughter Oshina after five years of laboring in a mine, with the one intent of saving her.

But he's told she died two years before, & he is broken by grief. A similar fate is awaiting Otane, & the grieving father of Oshina decides to liberate another man's daughter since it's too late to save his own.

By stages it begins to look like all things will end as well as can be expected. The primary cast is happy thanks to the inate goodness of people. The music swells with the joyfulness of life.

There has been a lot of human comedy along the road, in addition to drama & tragedy. The lighthearted spirit of events makes for a harsh, hard contrast to the eventual climax yet to come.

[SPOILER ALERT!] The young lord while himself drinking is insulted by obnoxious drunken samurai. [SPOILER ALERT!] The young lord while himself drinking is insulted by obnoxious drunken samurai.

The weaker of his two servants, Genta, is killed though unarmed, & Gonpachi is not present to even attempt to stop the tragedy. Sakawa puts up a good fight against the thuggish group of samurai, the same men as put on a big show of "rewarding" thief-catchers with a worthless letter of praise.

Sakawa is suprisingly strong in the battle, but one against several means he's taken down. When lancer Gonpachi arrives, his horror is palpable, his welling anger entirely comprehensible.

He's not a great spearman at all, but is so maniacal in his rage, he becomes a whirling terror, avenging his master with grotesque awkward vigour.

It will be a bitter victory, with his master & Genta just as dead. And the subtext is complex, in that Gonpachi represents faithfulness to the feudal system in avenging his lord, & criticism of the system in punishing samurai evil-doers. [END SPOILER ALERT]

Tomu Uchida was undeniably one of the great Japanese directors. Though his films have remained relatively little-known in the west -- compared to those of Ozu, Kurosawa, or Mizoguchi -- he's nevertheless cited time & again by specialists in Japanese cinema as one of the masters. And A Bloody Spear on Mount Fuji is frequently tagged as among the best of the best.

It marked a post-war "come back" for both Tomu Uchida as director, & for the film's star Chiezo Kataoka. Chiezo been one of the biggest chambara star in the silent film era & in war-time samurai films intended to impress upon modern Japanese the importance of the samurai spirit. It marked a post-war "come back" for both Tomu Uchida as director, & for the film's star Chiezo Kataoka. Chiezo been one of the biggest chambara star in the silent film era & in war-time samurai films intended to impress upon modern Japanese the importance of the samurai spirit.

But during the Occupation, such films were outlawed, & Chiezo's career went on hold. This break in his presence in new films could well have marked the end of his career, for he was getting up there in years & no longer a matinee idol.

MacArthur's suppression of samurai movies was obviously due to his belief that such films could only embolden the Japanese spirit with warlike propensity. But in fact, when the Occupation ended, jidai-geki was reborn with a vengeance. And very frequently that revenge was against the military establishment itself, tales of the cruelties of feudalism being not all that subtle a criticism of leaders who had more recently brought a nation to the brink of destruction.

After Chiezo's performance in Chiyari Fuji, he was recognized as a top character actor both for support roles, & in many starring vehicles of his own. Through the 1960s he experienced a continuous last hurrah, appearing opposite all the leading young stars at Toei Studios, plus having his own "samurai detective" films.

There'd be only a few serious art films to come, none quite the equal of A Bloody Spear on Mount Fuji, though Killing in Yoshiwara (Yoto monogatari: Hana no Yoshiwara hyaku-nin giri, 1960) would come awfully close, being another artful success for Tomu Uchida as well as for Chiezo. There'd be only a few serious art films to come, none quite the equal of A Bloody Spear on Mount Fuji, though Killing in Yoshiwara (Yoto monogatari: Hana no Yoshiwara hyaku-nin giri, 1960) would come awfully close, being another artful success for Tomu Uchida as well as for Chiezo.

Chiyari Fuji is a fascinating film in that it both romanticizes the Edo period, & undermines the romance of the samurai.

Lord Sakawa's sentimentality toward his vassals conveys his own desire that men be treated as equals despite a rigid class system, that a man's worth was in his character rather than his birth. It's an attitude that places him at odds with his own class, & is a contributing factor in his downfall.

Uchida had in fact been a confirmed Nationalist before & during the war. He had spent the war years in Manchuria by his own choice.

But he saw friends in the film industry sent to the warfront to die, as punishment for not producing films that served the military establishment sufficiently. But he saw friends in the film industry sent to the warfront to die, as punishment for not producing films that served the military establishment sufficiently.

Even before he saw Japan's dreams of conquest utterly defeated, Tomu had become ambivalent about militarism, adoring the romance of the samurai but liking less & less the realities surrounding him.

He began to feel "almost" susceptible to another romantic delusion, Maoism. That is not to say Tomu Uchida embraced Maoism; far from it. Exposure to it made him increasingly sympathetic with the common man, but beyond that, rather than being persuaded by Mao's philosophy, Tomu perceived the manner by which small mistakes of reasoning inevitably build upon one another until major catastrophes are the outcome. And this will be true whether the seed of error begins with idealized communism, or with the neo-feudalism of modern Japan's militarist aspirations.

The human condition, Tomu perceived, was one of contradiction, & Chiyari Fuji more than any other of his films expresses the central contradiction in terms of samurai ethos as enobling on the one hand & horrifying on the other, a system under which decency & compassion will not find reward.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|