One of the most significant films in the history of horror fiction, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Kabinett des Doktor Caligari, 1920) is essential to the understanding of German Expressionist cinema at its extreme edge.

One of the most significant films in the history of horror fiction, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Kabinett des Doktor Caligari, 1920) is essential to the understanding of German Expressionist cinema at its extreme edge.

This film had a profound influence on Hollywood cinema at least to the end of the film noir era. The influence has never entirely faded, right down to the present hour.

Had this not been genuine visual art, it would still have been influential as horror per se, for its story has been retold both artfully & artlessly time & again.

Hardly a year passes that another horror film doesn't appear regarding a madhouse wherein the inmates & caretakers are either swapped around or indestinguishable.

A sinister travelling carnival features a monteback, Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss).His primary program is the presentation of Cesare the Somnambulist (Conrad Veidt) who has slept within the miraculous cabinet for twenty-five years. In his perpetual half-sleep, he can be answer questions of the future.

A series of murders occurs when the carnival arrives, a mystery which Frances (Friedrich Feher) sets out to solve.

In his somnambulant state Cesare can be motivated like a puppet to obey the whims of Dr. Caligari (causing the character to be regarded by some horror fans as cinema's first zombie). In his somnambulant state Cesare can be motivated like a puppet to obey the whims of Dr. Caligari (causing the character to be regarded by some horror fans as cinema's first zombie).

Dr. Caligari turns out to be head of a mental institution. His medical specialty is somnabulance.

A sleepwalker-killer had been reported centuries earlier in Northern Italy, a case that obsessed Caligari.

The asylum's resident catatonic provided him with the opportunity to duplicate that infamous case, & going on the road as a carnival act permitted him to experiment with Cesare in locations that might not track back to his studies.

That the entire tale might be only a madman's dream adds another level of oddity to this classic.

But the main claim to deeper significance are the amazing angular & trapazoidal sets that shift one's sense of reality & make scene upon scene a window into a shadowy other-realm of psychotic silent nightmare.

The remake of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (2005) is a computer-altered version of the original. It scans all the original sets into an animation program, erases the original extraordinary actors, & replaces them with modern modiocre actors.

The remake of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (2005) is a computer-altered version of the original. It scans all the original sets into an animation program, erases the original extraordinary actors, & replaces them with modern modiocre actors.

Because the new actors worked against a green-screen & never interacted with actual sets, they never really seem to be on the sets.

It's to the original film what a Mona Lisa bath towel is to Leonardo da Vinci's painting. It's what a pair of magic x-ray glasses made of cardboard would be to a rainbow spanning the Orinoco Valley.

The deep mood achieved through the original's lack of spoken word is reduced to absurdist jibbering dialogue. Cesaer (Doug Jones) seems to be Edward Scissorhands in an amateur jazz dance number performed by square dancers, or a Sprockets skit in an old episide of Saturday Night Live.

The "computer graphics are cool" factor supplants the art factor of the original. The best bits in this tinkered-version are stolen thus least original, while the original moments are abjectly foolish.

Amazing costumes of the original are refashioned for new characters as crummy & flimsy. Stilted acting of characters floating in front of backgrounds is reminscent of back-projection FX of the 1960s or '70s cheapest sci-fi films, the sort of thing which would have a castaway running-in-place pretending to be chased by a rubber dinosaur.

The people who put this film together doubtless believe they did so with deep affection for the original, but what they really loved was grinding it up in a glorious beloved computer. This film amounts to assholes sneaking into an art exhibit with laundry markers in order to draw mustaches on masterpieces.

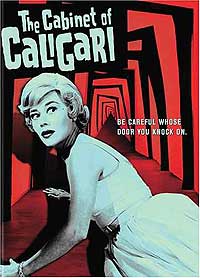

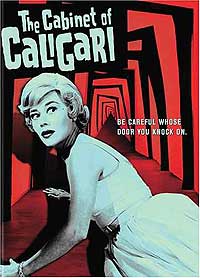

Her car breaking down sends a young woman, Jane (Glynis Johns), on a long walk down an empty highway, the jaunty beatnickish soundtrack slowly turning sinister for The Cabinet of Caligari (1962).

Her car breaking down sends a young woman, Jane (Glynis Johns), on a long walk down an empty highway, the jaunty beatnickish soundtrack slowly turning sinister for The Cabinet of Caligari (1962).

The first house she encouters is a rather bizarre mansion in a stagy Gothic Kitsch Deco style surrounded by large gardens & high security fences.

Caligari (never explicitely called a doctor but seemingly a psychiatrist even so) & a woman named Christine (Constance Ford) greet Jane & exchange sinister glances while offering to help. Christine goes off with an as-yet off-stage character to get Jane's car & tow it to the mansion promising to fix it, while Caligari & Jane get comfy in a sitting room.

Nonsensical dialogue like that from a dada play makes no earthly sense. The dramatic & surprisingly good score by Gerald Fried (who scored Roots in 1977 but generally just wrote incidental music for sundry television series) is used to pinpoint moments in the dialogue that are supposed to be suspenseful or important in some manner.

Without the score, the conversations would be even more idiotic. Everything spoken means little or nothing & in no way resembles how anyone would converse, though some bits do play off psychiatric jargon.

The script is by horror writer Robert Bloch. Though it's shockingly bad, Bloch was in his day noted for sadistic humor & his worst stories are hard to make much sense of unless you just go along with the jokiness. The script is by horror writer Robert Bloch. Though it's shockingly bad, Bloch was in his day noted for sadistic humor & his worst stories are hard to make much sense of unless you just go along with the jokiness.

The sharp b/w widescreen cinematography (by John L. Russell, who not coincidentally was behind the camera for Hitchock's & Bloch's Psycho) & the doomful musical score make The Cabinet of Caligari look & sound like a substantial movie, as does Glynis Johns, a pretty decent actor to turn up in such a film.

Yet nothing of the story or dialogue makes a lick of sense. The nonsensicality of the dialogue is intentionally surreal, but difficult to distinguish from ineptitude.

Discovering she's a prisoner, & the next day learning there are great many other captive residents who seem much happier than herself to be trapped, Jane begins to suspect a conspiracy. At one point, however, she witnesses the beating death of an elderly resident (delightful character actress Estelle Winwood).

For a while thereafter, the "explanation" for all the nonsensicality becomes, "You're sadists!" which magical word Robert Bloch was known to use as a key terror-word even in some of his novels & tales, mainly the stupid ones.

Jane makes one friend among the residents whom she trusts, Paul, who looks exactly like Caligari but without Freud's beard, as both characters are played by Dan O'Herlihly. The story meanders around the house & through the garden with many moods for Jane from terror, paranoia, anger, erotic acting out, with silly moments of being watched in her bathtub, almost accidentally killing someone, & trying to seduce Caligari.

It is a challenge to any puzzle-loving brain to try to make sense of these varied moments that skip from one disconnected event to the next.

[SPOILER ALERT] There is at long, long last a "revelation" as to what it all means, a kind of universal explanation that could've been pinned to the end of any number of random events: Jane's crazy.

In fact she's in the nuthouse & there is indeed a conspiracy, one of driving her sane. In fact she's in the nuthouse & there is indeed a conspiracy, one of driving her sane.

The attempt works & finally she realizes she's not a young woman kidnapped by insane tormentors, but a middle-aged or older woman constantly hallucinating the world around her in order to escape of the "real" horror of not being a young sexpot.

Paul & Caligari were imaginary people & a completely different person is her actual psychiatrist (Richard Davalos).

This outcome of the story is itself as random & foolish as anything else that has happened, so I half expected one more twist establishing she's still nuts & hallucinating that she's better. But in fact she really is better & she gets to leave the asylum. On her way out she sees that the woman whose death she witnessed is perfectly all right, apart from being a resident nut not yet cured. [END SPOILER ALERT]

The William Castle-esque promotion of this film in 1962 was that the final thirteen minutes were so shocking that even the unshockable would be shocked, & doors would be locked so no one would be permitted to leave the theater during those thirteen minutes.

It's actually a very dull thirteen minutes of talkiness at least six minutes longer than it needed to be, which is why I kept waiting for the final twist that never came.

It isn't often one encounters a film this foolish that has a surface gloss of competence. It must've seemed much better in the '60s seen by stoned hippies going, "Far out, man," at every ridiculous turn of dialogue.

But the idiocy of the thing most certainly was intentional & the film does exactly what was planned. So I'm sure there will be people other than the director & author who think it was a great success of outrageousness & nonconformist storytelling hipsterism.

Although sometimes listed as a "remake" of the silent classic, it has absolutely nothing to do with the great silent film whose title is misappropriated. There's a dream sequence of expressionist doorways alluding to the original, but nothing else. Not even a cabinet, unless the revolving door to Caligari's private office was supposed to symbolize a cabinet.

Continue to the next madhouse:

Session 9 (1991)

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

In his somnambulant state Cesare can be motivated like a puppet to obey the whims of Dr. Caligari (causing the character to be regarded by some horror fans as cinema's first zombie).

In his somnambulant state Cesare can be motivated like a puppet to obey the whims of Dr. Caligari (causing the character to be regarded by some horror fans as cinema's first zombie).

The script is by horror writer Robert Bloch. Though it's shockingly bad, Bloch was in his day noted for sadistic humor & his worst stories are hard to make much sense of unless you just go along with the jokiness.

The script is by horror writer Robert Bloch. Though it's shockingly bad, Bloch was in his day noted for sadistic humor & his worst stories are hard to make much sense of unless you just go along with the jokiness. In fact she's in the nuthouse & there is indeed a conspiracy, one of driving her sane.

In fact she's in the nuthouse & there is indeed a conspiracy, one of driving her sane.