The Celluloid Musashi Part I:

His Childhood, & Early Film Adaptations

In 1584 a child was born in the Yoshino ward of Miyamoto village in Mimasaka province. He was named Bennosuke, though he would also be known as Shinmen Takezo. It would be a long time yet before he was known as Musashi Miyamoto, wildman, master swordsman, artist, author, & Zen buddhist. In 1584 a child was born in the Yoshino ward of Miyamoto village in Mimasaka province. He was named Bennosuke, though he would also be known as Shinmen Takezo. It would be a long time yet before he was known as Musashi Miyamoto, wildman, master swordsman, artist, author, & Zen buddhist.

The infant's father immediately divorced the mother, for she had birthed a less than perfect son. Scar tissue marred the infant's pate. This deformity has been conjectured to be due to congenital syphylis, although the infant was healthy & sassy. The mother died & the father was close to insane.

That father, Shinmen Munisai, ran a dojo (martial arts training hall). He saw his son periodically, teaching him swordsmanship until the boy was seven. One day his father, believing he saw something inimical in the lad's appearance & wild manner, & not wishing to leave vile prodigy, drew his shortsword & threw it across the dojo, intending to kill the boy.

Alert & quick, the youngster fled to his guardian uncle, a priest. He never saw his father again, who shortly after died insane.

Although his great-grandfather Hirada Shokan had been a retainer of some importance to the Harima clan in Kyushu, by the generation of the child in question, the family's glory days were over. As an orphan, Takezo could expect very little out of life.

He became an extremely unruly youngster who nobody believed would amount to a thing. He went about with a wooden stick as though it were a sword. When he was not leading some pack of boys on a rampage, he was off by himself practicing swordsmanship with his stick.

The year before the assassination of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a man named Arima Kibei came to Miyamoto village. He had become famous for his Shinto-ryu sword style, was expert in yari-jutsu or spear-art, & had never lost a duel. The year before the assassination of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a man named Arima Kibei came to Miyamoto village. He had become famous for his Shinto-ryu sword style, was expert in yari-jutsu or spear-art, & had never lost a duel.

He set up camp & had an aide place a placard in a conspicuous place along the road. It read: "Arima Kibei will accept the challenge of any brave man."

Today such actions seem motivated by nothing more than childish boastfulness. In its historical context, Arima's behavior was not only acceptable, but expected.

After centuries of civil war, Hideyoshi had succeeded in unifying Japan. Though war was not yet a thing of the past, it was at least no longer endemic. Lords did not require thousands of retainers. The samurai class was increasingly underemployed.

A lowly farmer might be better off than a samurai. Thus the samurai sought to convey their social status through methods other than material prosperity.

Part of their method was to relish their poverty, to consider austerity a strengthening lifestyle, one which kept them ever ready for the nation's return to arms. Another method of proving their status, readiness, & strength was to enter life-risking contests with other swordsmen.

These duels were called taryu-jiai. They were usually but by no means always fought with wood swords or bokken. Witnesses would be present at the dojo or open field. These were not necessarily duels to the death, but they must at least provide a decisive winner, & if one or the other were in fact killed, nothing could be more decisive.

In peacetime, taryu jiai was the samurai's only sanctionable method of proving warrior excellence. Within the samurai's peer group, these duels were of inestimable social importance. The outcome could be victory with attendant glory all out of proportion to the measurable value of the encounter. Defeat would be attended by inordinant disgrace.

In theory samurai eschewed wealth. But fame they did not eschew in the least; it was fervantly sought. Taryu-jidai was their chance to gain recognition among fellow samurai &, with luck, to be noticed by some lord, thereby offered a station (together with the creature comforts theoretically eschewed).

To be in the service of a lord was a samurai's ultimate goal, for to be a samurai meant "to serve," & a samurai gained much of his self-identity through a master. The word ronin originally meant "displaced person" & could be applied to a farmer who left his farm as well as a samurai who lacked a master. It came to be applied to unemployed samurai exclusively, carrying derogative connotations from its earlier usage.

Once the goal of becoming a retainer is achieved, a swordsman would no longer be permitted to participate in taryu-jiai or any other activity not intended exclusively for the glory of one's lord.

Very occasionally a ronin would achieve such a level of self-pride that vassalage was unthinkable, & to some degree Musashi Miyamoto would become that sort of independent swordsman. Of course, Musashi would have disciples among great lords, so he was not torn by the discouraging sense of failure that haunted so many ronin that suicide was often considered a reasonable option to continued life without a master.

On that day when Arima Kibei had his sign put up, a boy of thirteen years happened to heading home from parochial school (terakoya). He stopped & read the sign.

On that day when Arima Kibei had his sign put up, a boy of thirteen years happened to heading home from parochial school (terakoya). He stopped & read the sign.

He was big for his age, & in need of a bath. Unlike many boys, no part of his head was shaven & he did not have a topknot. His hair wasn't even combed. His kimono was not tied up properly & thus dragged on the dusty road. He was the town bully, not much liked by anybody.

The boy took ink & paper from among his school supplies, wetted the brush with his tongue, & wrote a response to attach to the public signboard: "Shinmen Takezo will fight Arima Kibei tomorrow."

Arima Kibei was bound by his cultural ethos to accept any challenge. Takezo's guardian, the priest, had to get the boy out of it somehow. He went with Takezo to the dueling field the next day, planning to apologize for the childish mischief.

Arima had advance notice of the priest's intended intervention, & was prepared to accept the apology, there being no glory in beating up a kid who didn't even own a sword.

No one had asked for Takezo's opinion. He remained silent until they reached the dueling field. Then he pulled up a post of some six shaku length, roughly twice the size of an ordinary sword. He swung it ferociously. Before the priest could say a word in Takezo's behalf, the boy shouted crazily, "Don't sit there like a lump! Come fight me & die!"

Arima was surprised by such ferocity. Though the challenger was a child, he was of good height, obviously strong, & not to be brushed aside or ignored. Taken off guard, Arima could only draw his steel bade to deflect Takezo's rapid onslaught. Takezo attacked a second time, before Arima could recover.

The long wooden post struck Arima & knocked him flat. The vicious lad proceeded to beat the downed man mercilessly, breaking a number of bones, including those of the skull. Needless to say, Arima did not survive the day.

Word of the duel spread like wildfire. A kid with a board defeated the best known swordsman of the region! Young Takezo, later Musashi Miyamoto, acted indifferent to public acclaim. He wanted only to pursue swordsmanship & prepare for further taryu-jiai encounters in the years to follow.

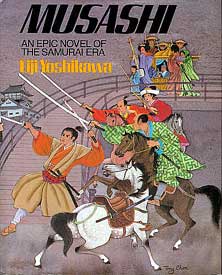

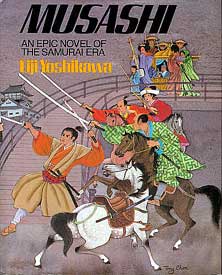

The famous novel by Eiji Yoshikawa (1892-1962) about Musashi's life begins much later than these events of his childhood. Yoshikawa's novel is the basis of the most popular sentimental understandings of who Musashi was as a man. The novel romanticizes & alters his nature, inventing a more appealing character, a priest having supposedly tamed the slovenly half-feral boy.

The famous novel by Eiji Yoshikawa (1892-1962) about Musashi's life begins much later than these events of his childhood. Yoshikawa's novel is the basis of the most popular sentimental understandings of who Musashi was as a man. The novel romanticizes & alters his nature, inventing a more appealing character, a priest having supposedly tamed the slovenly half-feral boy.

The real Musashi did have noble qualities. He became a gifted artist, author, & swordsman. But he also retained his tendancy toward slovenliness throughout life. Though he had important friends & devoted students, none of them could induce Musashi to bathe or comb his hair.

By the Japanese standard of cleanliness, Musashi was unmitigated grossness. But men of talent & charismatic personality are often forgiven the kind of eccentricities which would make ordinary men outcasts.

This slovenly Musashi is not the man Eiji Yoshikawa popularized, though other books would delight in being more truthful, ammending the white-washed portrait.

Serialized in the prestigious, widely circulated newspaper Asahi Shimbun from 1935 to 1939, Yoshikawa's lengthy novel Musashi Miyamoto has forever after remained in print, in various editions, & sold millions of copies.

In 1981 Kodansha published an English language edition, but Musashi was already well-known to English-speaking audiences because of the Oscar winning film by Hiroshi Inagaki, based on Yoshikawa's novel, & in which international superstar Toshiro Mifune stars in this version as best known in the west as Samurai Trilogy (Miyamoto Musashi, 1954-55).

The film trilogy, like the novel, never comes to grips with the historical Musashi, preferring to make his wilder aspects a passing phase of youth. From naive, crazy, animalistic behavior, he progresses toward an increasingly wholesome figure, until finally he has become so sensitive that he regrets the death of his greatest opponent, Kojiro, a lovely fiction but not history.

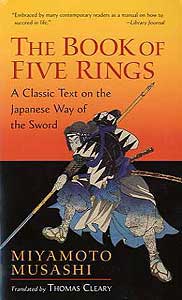

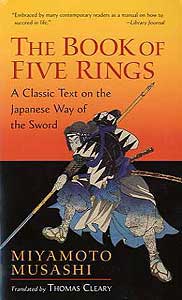

As evidenced by Musashi's own words in The Book of Five Rings, every victory was considered in retrospect for what was accomplished tactically. His last days were spent recording his philosophy of opportunistic tactics with no hint of regret where snuffed lives were concerned.

It's no wonder this book was to become a cult classic for cold-blooded Wallstreet business men in America, or that it inspires cutthroat policies in Japan's highly successful international business relationships.

Edwin O. Reischeur, Harvard professor & historian, called Yoshikawa's novel the Gone with the Wind of Japanese literature & cinema, meaning it's historicity is practically zilch, but in terms of lasting mass appeal, it's got it in spades.

Edwin O. Reischeur, Harvard professor & historian, called Yoshikawa's novel the Gone with the Wind of Japanese literature & cinema, meaning it's historicity is practically zilch, but in terms of lasting mass appeal, it's got it in spades.

Stylistically Rafael Sabatini's work would be closer to the kind of books Yoshikawa pumped out one after another. Scaramouch & Musashi Miyamoto are the same kind of romantic swashbucklers, taking the same licenses with history.

Yet while Sabatini has fallen from mass popularity, Yoshikawa's work, particularly his vision of Musashi, has become part of the Japanese subconscious self-identity. No matter how westernized Japan becomes, Yoshikawa's Musashi cannot be set aside.

Like Sabatini's epics, Yoshikawa provided prime material for classic adventure cinema. Kenji Mizoguchi's New Tales of the Taira (Shin Heike monogatari, Daiei, 1954) was not based on the eleventh century poem, but on Yoshikawa's romantic retelling. The two-part film Shinran (1960) starring Kinnosuke Nakamaura as the Buddhist monk was likewise adapted from a Yoshikawa pulp novel.

His Musashi novel formed the basis of many films beginning with a black & white trilogy starring Chiezo Kataoka, released in 1940, directed by Hiroshi Inagaki who would later remake the saga in color starring Toshiro Mifune. Tomu Uchida would direct a six-film screen adaptation which is really the best version though not half as well known in the west. The same novel inspired a television series that ran in 1984-85 starring Koji Yakusho, then a mini-series that aired in 2003 starring Shinosuke Ichikawa.

Only a little of this popularity predates Yoshikawa's novel. Musashi was known among art historians & collectors. He had a tiny but devoted cult following among martial artists due to his works Thirty-five Articles of Swordsmanship & The Book of Five Rings (actually five small books titled Earth, Water, Fire, Wind & Void). And he'd been a rowdy figure of the kabuki theater which lent cinema so many of its standard characters.

Until Yoshikawa's book popularized Musashi more favorably, he was not in general thought of in the highest regard, do to the fact of his "tactics" which many considered mainly dirty tricks & not very honorable. The kabuki stage traditionally favored Sasaki Kojiro, Musashi's chief rival, a classic "folk hero" of the type described in Ivan Morris's The Nobility of Failure (1975).

The plays portray Kojiro as a beautiful well-groomed young man of twenty-five or so, though in fact he would have been much older if he existed at all. His nemesis, Musashi, was portrayed on the stage as scruffy, middle-aged, though in reality he may well have been the younger man. The middle-aged Musashi of kabuki uses all manner of deceptive tricks to win, closer to his historical character than Yoshikawa's novel, though Yoshikawa preserved the character of Sasaki Kojiro pretty much unchanged from the traditional portraits..

Gan-ryu (the name of a sword school presumedly founded by Kojiro, & a name often applied to him as an individual) became the name of the island where Kojiro died; it had previous been called Funajima. A memorial erected on that island does not commemorate the fateful duel per se, nor Musashi who was victor. It is in commemoration of the brave man who died at the hand of a trickster of dubious character.

Musashi was also never held up as the ideal swordsman by the kodan or heroic storytellers, due to his vicious streak & his bad grooming & manners. He was admitted to have been a Zen questor with deep thoughts, but his flaws were greater than his good points. Therefore it took a work of elaborate fiction to make Miyamoto Musashi truly a heroic type; & a large body of cinematic representation in the wake of that novel's success hugely revamped his image.

The earliest silent films, from the 'teens or even earlier, contained little in the way of plot & characterization. Filmmakers all too often had to be vague about what they portrayed, so as not to interfer with a benshi's stories. A benshi was a narrator at the movie houses & he was commonly regarded the actual star of the place, the actors on the screen being exceedingly popular but nevertheless secondary.

The earliest silent films, from the 'teens or even earlier, contained little in the way of plot & characterization. Filmmakers all too often had to be vague about what they portrayed, so as not to interfer with a benshi's stories. A benshi was a narrator at the movie houses & he was commonly regarded the actual star of the place, the actors on the screen being exceedingly popular but nevertheless secondary.

Mushashi was not an important screen figure before Yoshikawa's novel began serialization, so not a big figure in the benshi repertoir, thus not common in silent cinema. But he was not absent either, as Musashi did have his historical place & had been portrayed on the kabuki stage.

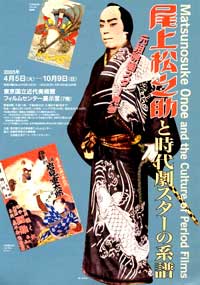

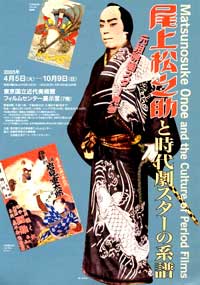

The first actor to play him repeatedly was Matsunosuke Onoe, earliest in Miyamoto Mushashi (Nikkatsu Tokyo, 1914) directed by Shozo Makino who discovered him in 1909 as an itinerant kabuki player. He played Musashi as late as in Mushashi Miyamoto: His Duel with Bokuden Tsukuhara, (Miyamoto Musashi tai Tsukahara Bokuden, Nikkatsu Kyoto, 1924), with Bokuden played by Sennosuke Nakamura. There were a couple of others in between.

Alas, not even fragments survive of Onoe's characterizations of Musashi, so only the broadest assessment can be hazarded, based on what little of his work does survive. The director of the 1924 version, Yaroku Kobayashi, was still making films by earlier, primitive techniques, offering the viewer no more than a tableau which a benshi would describe in detail, not from any script but form his own established repertoir.

Matsunosuke Onoe was enormously popular in more than a thousand quickly made silent movies. Yet he shared his director's lack of comprehension of the changes inevitable in the movie industry, which benshi quite naturally resisted. Since benshi frequently owned the cinema houses or had enormous reputations among the public, it was difficult for producers, directors, or actors to advance their art.

Onoe wasn't one to buck the system & brought no iota of character to distinguish one of his roles from the next. His fellow silent film idol, Chiezo Kataoka, was much more interested in pushing back at the influence of the benshi & making films that stood on their own, but not so Onoe. And he would die in 1926 of a heart ailment, before seeing anyone portray Musashi well. Onoe wasn't one to buck the system & brought no iota of character to distinguish one of his roles from the next. His fellow silent film idol, Chiezo Kataoka, was much more interested in pushing back at the influence of the benshi & making films that stood on their own, but not so Onoe. And he would die in 1926 of a heart ailment, before seeing anyone portray Musashi well.

After the appearance of the novel, numerous studios rushed versions to the screen. Eisuke Takizawa lavishly directed Miyamoto Musashi: The Earth Scroll (Mushashi Miyamoto: Chi no Maki, 1937) for the star's own company, Arashi Kanjuro Productions (just for confusion sake, the same year Chiezo Kataoka starred a version with the same title).

Arashi Kanjuro was known lovingly to his fans as "Arakan" & he'd been a major film idol beginning in the silent era when he went by Arashi Chozaburo.

In 1937 he was still fairly youthful in his appearance & played a rather pretty Musashi. His co-stars included Shosaku Sugiyama as his beautiful opponent Kojiro & in the female lead, Mineko Mori as Akemi & Shizuko Mori as Otsu. In 1937 he was still fairly youthful in his appearance & played a rather pretty Musashi. His co-stars included Shosaku Sugiyama as his beautiful opponent Kojiro & in the female lead, Mineko Mori as Akemi & Shizuko Mori as Otsu.

In the three-character portrait are shown left to right Shosaku Sugiyama, Mineko Mori, & Areshi Kanjuro in a scene from the film.

The stills reproduced here are sufficiently beautiful that we may lament that only a fragment is available on the video Arashi Kanjuro Kessakushi (Arashi Kanjuro's Greatest Roles, 1983).

He began his career in 1927 at Makino Films & soon excelled at swordplay films. He founded his own company very soon after. He pretty much established the screen personas of Kurama Tengu (1928, & sequels), the hooded foe of the shogunate attempting to re-establish the Emperor as true sovereign.

He simultaneously starred in the Detective Umon series & played him from 1929 to 1955, defining the role to Ryutaro Otomo. He simultaneously starred in the Detective Umon series & played him from 1929 to 1955, defining the role to Ryutaro Otomo.

He continued his career into the 1970s, playing character roles in his old age, & appearing in numerous chivalrous-style gangster films or yakuza-eiga of the 1960s.

Arakan's Musashi film was soon followed up by The Wind Scroll (Miyamoto Musashi: Fu no Maki, Toho Studio, 1938) starring Yataro Kurokawa as a rougher Musashi, this latter film directed by Seiichi Ishihashi. Hiroshi Makimoto wrote the script. Mitsuko Takao played his girlfriend Otsu, & Shonosuke Sawamura was Kojiro.

The "Earth Scroll" & "Wind Scroll" titles referred to segments of Musashi's Book of Five Rings, even though the films were hurried to the screen because of the overwhelming popularity of Yoshikawa's serial, on which they were loosely based.

Some of the Musashi films which were inspired by Yoshikawa's work, including these from 1937 & 1938, reached the public before the serial was even completed, as also happened with Yoshikawa's later serial, Shin Heike Monogataro.

Additional films inspired by early chapters of the still-in-progress serialized novel included Ryuzo Otomo's Musashi Miyamoto (Miyamoto Musashi, Daito, 1936) starring Michitaro Mizushima as Musashi; remade by the same director at the same studio in 1938 but with Sozaburo Matsuyama as Musashi; & Kazuo Mori's Musashi Miyamoto (Miyamoto Musashi, Shinko, 1938) with Hideo Otani as Musashi.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

The year before the assassination of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a man named Arima Kibei came to Miyamoto village. He had become famous for his Shinto-ryu sword style, was expert in yari-jutsu or spear-art, & had never lost a duel.

The year before the assassination of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a man named Arima Kibei came to Miyamoto village. He had become famous for his Shinto-ryu sword style, was expert in yari-jutsu or spear-art, & had never lost a duel.

Onoe wasn't one to buck the system & brought no iota of character to distinguish one of his roles from the next. His fellow silent film idol, Chiezo Kataoka, was much more interested in pushing back at the influence of the benshi & making films that stood on their own, but not so Onoe. And he would die in 1926 of a heart ailment, before seeing anyone portray Musashi well.

Onoe wasn't one to buck the system & brought no iota of character to distinguish one of his roles from the next. His fellow silent film idol, Chiezo Kataoka, was much more interested in pushing back at the influence of the benshi & making films that stood on their own, but not so Onoe. And he would die in 1926 of a heart ailment, before seeing anyone portray Musashi well. In 1937 he was still fairly youthful in his appearance & played a rather pretty Musashi. His co-stars included Shosaku Sugiyama as his beautiful opponent Kojiro & in the female lead, Mineko Mori as Akemi & Shizuko Mori as Otsu.

In 1937 he was still fairly youthful in his appearance & played a rather pretty Musashi. His co-stars included Shosaku Sugiyama as his beautiful opponent Kojiro & in the female lead, Mineko Mori as Akemi & Shizuko Mori as Otsu. He simultaneously starred in the Detective Umon series & played him from 1929 to 1955, defining the role to Ryutaro Otomo.

He simultaneously starred in the Detective Umon series & played him from 1929 to 1955, defining the role to Ryutaro Otomo.