Medieval Yakuza Part II:

Chuji of Kunisada,

Not to Mention Yojimbo

Commoners did not have family or clan names & Chuji Kunisada should be understood to mean Chuji of Kunisada, a village in what is today Gumma Prefecture. Chuji was a wandering gambling boss or late medieval yakuza oyabun who wandered the highways of the Kanto region doing good deeds, assisting fellow commoners when tyranny of government or gangsters less noble than Chuji caused grief.

Commoners did not have family or clan names & Chuji Kunisada should be understood to mean Chuji of Kunisada, a village in what is today Gumma Prefecture. Chuji was a wandering gambling boss or late medieval yakuza oyabun who wandered the highways of the Kanto region doing good deeds, assisting fellow commoners when tyranny of government or gangsters less noble than Chuji caused grief.

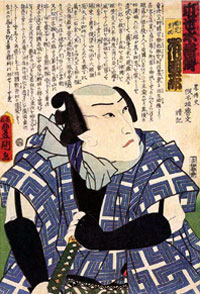

He is celebrated in a Tokugawa period short stories & plays about ototodate chivalrous commoners, & outlaws regarded as "heroes of the water margins" borrowing themes from a "Japanized" version of a Chinese classic that celebrated outlaws. He became the subject inevitably of ukiyo block prints, an example by Utagawa Toyokuni III reproduced here, an actor-portrait entitled "Ichikawa Danjuro as Kumisada Juji," from the early 1860s.

Although a legendary figure, a romantically inclined historians have made the attempt to prove Chuji was a real person or at least grew out of an historical character type. It is always taken for granted in folksongs, plays, books, & movies that Chuji existed & was a chivalrous fellow devoted to a gambler's code called kikotsu which did not permit the harrassment of honest people.

In Chuji's world view, it was one thing to set up illegal gambling dens wherein gamers had a very small chance of winning even if the games were honest, vs shaking down decent citizens who never set foot in a gambling den. So whether it was yakuza within his own world, or corrupt government officials, Chuji had no qualms standing up against them.

In popular tales Chuji has as much likelihood of being an immoral man as does his British equivalent of Robin Hood. He may be a criminal, but he's a hero to the people. And yet unexpectedly, Chuji is the third bad gangster boss hunted down by Jokichi of Mikogami in the Trail of Blood trilogy. Jokichi has every justification to disbelieve Chuji is the archetypal "good" yakuza eager to help commoners. It's one of the very few such cinematic epics to malign Chuji's character.

A more typical Chuji drama would be Gambler Tales of Hasshu: A Man's Pledge (Hasshu yukyoden: Otoko no sakazuki, Toei, 1963) written by Kinga Naoi & directed by Masahiro Makino. The trailer advertising this film is a winner in itself, boasting "new faces at Toei," none other than Shinichi "Sonny" Chiba & Junko Fuji! A more typical Chuji drama would be Gambler Tales of Hasshu: A Man's Pledge (Hasshu yukyoden: Otoko no sakazuki, Toei, 1963) written by Kinga Naoi & directed by Masahiro Makino. The trailer advertising this film is a winner in itself, boasting "new faces at Toei," none other than Shinichi "Sonny" Chiba & Junko Fuji!

Chiba's role was sappy & weak. He played the young son of an aging magistrate & was completely helpless against cruel yakuza. His one virtue in the film was his strong taiko or festival drum performance. The powerful guys he became known for were not yet recognized as his true forte.

Nor was Fuji Junko quite the powerful character she would be within a few short years. Yet even at this early date, she was given lines like, "If I were a man, I'd knock them down!" foreshadowing her eventual status as the "queen of yakuza" in films like the Hibotan bakuto Red Peony Gambler series.

The extraordinary character actor Takashi Shimura (the leader in Seven Samurai) is convincing, dignified, & sorrowful as the aging magistrate pressured by evil gamblers. But the inescapable star of the show is Cheizo Kataoka as the wandering gamblers' boss Chuji Kunisada.

The year is 1850. As the story begins, we are led to believe Chuji was executed a year earlier & there is no longer any hero who can help the peasants. The worst sorts of yakuza have taken over the town, demanding fees in order for an important festival to operate unmolested.

A fellow named Genji wanders into town & people slowly begin to suspect him of being Boss Chuji or Boss Jirocho or some other chivalrous commoner. Genji insists he's not any of the great bosses they suspect, & there are witnesses to Chuji's execution besides. In many Chuji films he takes on just such alternate personalities, & Chiezo Kataoka is particularly good at shifting from persona to persona & presenting a dynamic Chuji.

As the name Genji has been associated with gentlemanly behavior since A Tale of Genji was written in the Heian Period, this particular Genji allows the evil boss to have his way for as long as possible. Eventually things go too far when the kindly old magistrate is murdered. Genji then reveals he is indeed Chuji Kunisada, & shows his stuff in a climactic one-against-all battle.

Although terribly familiar, the story is handled with finesse, which can be said of just about any film starring Chiezo Kataoka, a classically trained actor with a brilliant sense of how to express himself through film. Toei in the post-Occupation era revived his career which had fallen moribund while McArthur was in Japan with a ban on jidaigeki or swordfight films keeping many former matinee idols unemployed.

Chiezo was doubtless glad to be back in the chips, but just as importantly, Toei Studios provided him a good deal of respect in providing him with well-plotted, well-edited films often enough with striking photography as in A Man's Pledge filmed in striking black & white, with top supporting actors.

Certain elements of this film may be contrived, such as when the aging magistrate finds out Chuji is coincidentally his long-lost son, abandoned as an infant forty years before. But Kataoka & Shimura are such fine actors, & play it so sincerely, the viewer is willing to suspend any tendency to disbelieve the premise.

One great line of dialogue captures the essence of the Chuji character. The man executed in Chuji's place is quoted as having said, "A hundred Chujis will be born, for as long as people are oppressed." At the bottom of the Chuji legend is not so much hero-worship as a belief in the potential for nobility from the common masses.

Before reviewing another Chuji film I want to meander onto a major aside about Akira Kurosawa's great classic film Yojimbo (1961). Before reviewing another Chuji film I want to meander onto a major aside about Akira Kurosawa's great classic film Yojimbo (1961).

It is interesting to contrast Yojimbo with any number of films about Chuji Kunisada, because Kurosawa rebelled against this whole idea of chivalrous yakuza when directing his outstanding but politically right-leaning action-comedy.

Chuji appealed to directors of Keiko-eiga or left-leaning-films, willing to believe in commoners as kokaku town knights or or otokodate daring fellows of heroic demeanor. Kurosawa liked personally to be addressed as Taisho or Emperor, & he had great disdain for anyone he perceived as beneath himself, he being descended through the samurai class.

Kurosawa has his two yakuza gangs & their merchant cohorts completely ruining a town, saved by the strong will of a masterless samurai who manipulates the gangs into destroying themselves while competing for the samurai as their bodyguard. In an interview with Joan Mellen, Kurosawa said he made Yojimbo specifically because, "I was fed up with the world of the yakuza." By contrast he was never alarmed by the romanticization of the buke class or its birthright in killing peasants for any reason or no reason or only to test a sword.

Yojimbo predates the rise of ninkyo eiga chivalrous gangster films set in the Meiji & Showa eras (filmed mainly from about 1963 to about 1972) & which indeed went overboard making gangsters seem like the last bastion of heroic nobility. Yojimbo predates the rise of ninkyo eiga chivalrous gangster films set in the Meiji & Showa eras (filmed mainly from about 1963 to about 1972) & which indeed went overboard making gangsters seem like the last bastion of heroic nobility.

Kurosawa just couldn't imagine it; he had primarily a reactionary response to those tales & films in which commoners living under feudalism are abused by authority, meaning the buke or military class or samurai, until some town knight or chivalrous commoner among the yakuza stands up to the bloody awful corrupt samurai.

Kurosawa's world view evades the fact that samurai, just like yakuza, were a burden to peasants, as he set out to redress the mythology very one-sidedly.

Sanjuro Kawabatake, the heroic ronin played by Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo, is no more or less likely a hero than Chuji Kunisada. Kurosawa's dislike of medieval yakuza archetypes is in many ways justifiable; but his reactionary portrait is a return to the status quo that assumes samurai are the superior humans, & that is equally a lie.

It would almost seem to be sour grapes of someone who is himself descended of the samurai class, wearying of films showing commoners like Chuji capable of cutting down Sanjuros three at a stroke.

The samurai were always a minority in Japan, though a ruling minority. While some have called them "the flowers of Japan," others have called the samurai the millstone at the neck of the peasants. Modern Japanese might well feel spiritually oppressed by the romance of the samurai, their own ancesters having been farmers or merchants or craftspersons & actually useful for something.

That feeling of oppression might seem especially annoying when the romance of the samurai has to be done, as in Yojimbo, at the expense of the dignity of commoners, who range from abuse victims to psychopaths (Tatsuya Nakadai) & narry a hero among them.

Yojimbo attempts to deny the fact that ronin were capable of great cruelty the same as yakuza. But worse, a ronin even in his poverty still had the the legal right to kill anyone & everyone beneath his station, as the Yojimbo kills all these. The yakuza on the other hand had no legal right to kill people, & got away with it only by paying off corrupt officials of the samurai class.

I like to believe that among a tremendous number of ronin, heroes of the kind represented in Yojimbo occasionally arose. But that is not a possibility that needed to be underscored by the assertion that among a tremendous number of yakuza commoners, there could never have been a Chuji Kunisada.

The feudal yakuza came from every class strata. Chobei of Banzui was a townsman (chonin) with a ronin father. Jirocho of Shimizu was of the merchant class (akindo). Another historical otokodate leader named Shimmon Tatsugoro was originally a farmer (heimin) who achieved the rank of hatamoto for services to the shogunate, effectively changing his class position. The fictional wanderer of the Trail of Blood series was of the artisan class (shokunin). The feudal yakuza came from every class strata. Chobei of Banzui was a townsman (chonin) with a ronin father. Jirocho of Shimizu was of the merchant class (akindo). Another historical otokodate leader named Shimmon Tatsugoro was originally a farmer (heimin) who achieved the rank of hatamoto for services to the shogunate, effectively changing his class position. The fictional wanderer of the Trail of Blood series was of the artisan class (shokunin).

Many authors have wanted to note that early yakuza included many descendants of the buke military class both among their ranks & leadership, but it would be an injustice to commoners to credit ex-samurai with medieval wanderers' & gamblers' grass-roots organizing.

Gang bosses hired ronin to be military instructors to their henchmen & heirs, or hired them as bodyguards as in Yojimbo. Some fallen samurai married into gangster families, adding military blood to yakuza family trees. But for the main, yakuza, for better or worse, is something that arose from the common masses.

Senkichi Taniguchi's Chuji the Gambler (Kunisada Chuji, Toho, 1960) has long been America's most accessible film about Chuji. Senkichi Taniguchi's Chuji the Gambler (Kunisada Chuji, Toho, 1960) has long been America's most accessible film about Chuji.

Also distributed under the misnomered title The Gambling Samurai though Chuji is a one-sword yakuza not a two-sword samurai. The title has been corrected on a more recent DVD release.

The film has long had distribution in the West because it starred Japan's first international superstar, Toshiro Mifune. He plays Chuji of Kunisada without his usual wit & wordplay. Even Chuji's famous speech addressed to his sword is reduced to two quick sentences so that Mifune may restrict his performance to the physical & not risk too much with dialogue, such as is much less his forte. In consequence he is not the most effective Chuji because Chuji ideally is the strong mouthy type, not the strong silent type.

On the other hand, a hoary tale is taken more seriously than usual & the violence & gloom of the tale is surprisingly intense for a family film. The author of the screenplay was Kaneto Shindo, himself a left-leaning director ideal for writing about this traditional rebel. Shindo's most famous film is the anti-samurai horror film Onibaba (1964). By alarming contrast, Senkichi Taniguchi who directed this Chuji feature is best known in the west for a seedy spy film which Woody Allen "re-sounded" as What's Up, Tiger Lily? (1966).

Chuji returns to the village of Kunisada after a period of exile only to discover that his mother has died of grief after his sister Kiku (Kumi Mizuno) was raped & driven insane by the magistrate Jubei (Susumu Fujita). The heiman or farmers are starving due to paying taxes (in rice) during a year of poor crops, having nothing remaining for their own families. Basically the village of Kunisada has gone to hell in a handbasket.

Chuji abusively chastises the man who was supposed to have been his sister's betrothed. Chuji abusively chastises the man who was supposed to have been his sister's betrothed.

That fellow becomes so guilt-ridden that he makes a suicidal raid against the magistrate's residence getting himself mortally wounded without getting anywhere near evil Jubei.

Then Chuji's sister stabs herself & falls dead on her betrothed's corpse. Chuji & his immediate lieutenants make a revenge raid on the magistrate's house & do manage to rip open the rice storage house but the magistrate escapes with only a wound.

Branded as a rebel against the government, Chuji hides out on Mount Akagi. The magistrate peevishly persecutes all gamblers, driving many into Chuji's mountain forests.

Through all, Chuji remains gruff & unhappy. When he learns that an elderly farmer (Masao Oda) has been arrested for sneaking food up to the mountain hide-out, Chuji comes down alone from his retreat for a one-against-all battle in the village streets, learning his elderly friend had been beaten but then released.

Another old friend, Kansuke (Eijiro Tono), although a magistrate, is a decent fellow who secretly supports Chuji though he must put on a good show of intending to arrest him, while actually giving him a chance to escape. Another old friend, Kansuke (Eijiro Tono), although a magistrate, is a decent fellow who secretly supports Chuji though he must put on a good show of intending to arrest him, while actually giving him a chance to escape.

Back on Mount Akagi, Chuji gruffly dismisses Asataro from his service, though Asa has always been one of his two or three absolutely most faithful men. Chuji fails to explain that his motivation is to have Asataro return to his uncle, the good magistrate, to become a family man instead of a gangster. But another of Chuji's men, Gentetsu (Yu Fujiki), witnesses Kansuke's attempted "arrest" of Chuji, & tells the young man that Chuji no longer wants him around because his uncle tried to make the arrest.

This leads to what is likely the most unjust & horrible event of the entire Chuji legend, when Asataro attacks his own beloved uncle to avenge Chuji. As the man is dying, he tells his nephew he had actually assisted Chuji, but if Chuji thought the arrest attempt was sincere, then "Take my head to him" so that Asa might be reinstated in the gang. Asa returns to Mount Akagi, bringing his uncle's head & his six year old orphaned nephew (Kankuro Nakamura).

Chuji is horrified & the famous head-viewing scene is done with tears all round. Chuji disbands his woodland outlaws sending them to the four directions of the compass, straps the young boy to his back, & descends with just his three most faithful lieutenants to face the evil magistrate.

Leaving little Kantaro temporarily with Chuji's girlfriend Toku (Michiyo Aratama), & assisted by Asataro, Gensuke, & Enzo (Daisuke Kato, who was Shichiroji in Seven Samurai), they battle their way through magistrate Jubei's men. The final one-on-one duel with Jubei's spear vs Chuji's sword is excellently staged, & after a protracted fight, vengeance is achieved for Chuji's sister & her fiance.

Finally strapping the boy to his back once again, Chuji takes off on the open road, intent on raising Kansuke's son as his own.

The film's color scope cinematography is pleasant & occasionally artistic, but the film is in the main very commercial in look & intent. It assumes familiarity with the Chuji legend & does not always explain itself for the average western viewer, but it's a simple enough tale to be largely accessible. It has to be approached not as a serious period film but as a cornier sort of rapidly paced family film, enjoyable as such.

Because Mifune's performance redacts Chuji's character, he is not as much fun in the role as are Chiezo Kataoka or Ryutaro Otomo, but he's fun to watch perform even so.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|