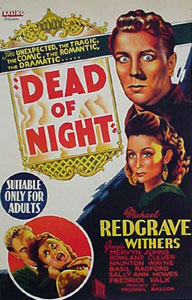

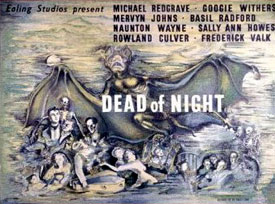

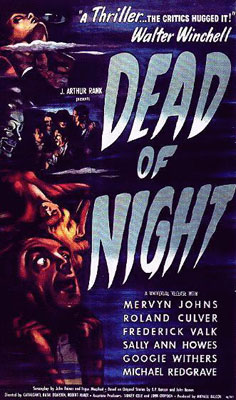

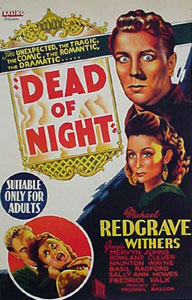

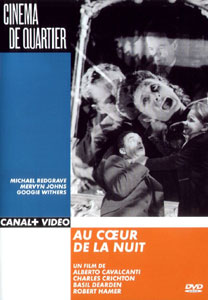

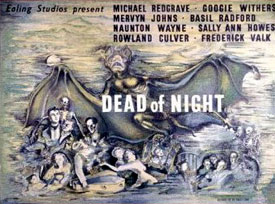

Dead of Night (1945) is one of the earliest horror-omnibus or anthology films. It tells five short tales with four different directors, expertly & smoothly knitted together by a sixth tale, the wraparound narrative. Such films are sometimes called "portmanteaus" after a travel-trunk holding odds & ends.

Dead of Night (1945) is one of the earliest horror-omnibus or anthology films. It tells five short tales with four different directors, expertly & smoothly knitted together by a sixth tale, the wraparound narrative. Such films are sometimes called "portmanteaus" after a travel-trunk holding odds & ends.

Earlier examples of the horror portmanteau begin with the German Expressionist silent film Waxworks (1924), followed in time by such excellent examples as Tales of Manhattan (1942) which is a set of short films about people whose lives are impacted by a cursed tuxedo, Flesh & Fantasy (1943) with three tales built around ironies that amount to the supernatural.

Arguably even Disney's Fantasia (1940) qualifies, as it is fantasy rather than horror, but for one episode of horror, "Night on Bald Mountain."

Even though not "first," Dead of Night would be the most important in establishing a veritable sub-genre of supernatural portmanteaus. Even though not "first," Dead of Night would be the most important in establishing a veritable sub-genre of supernatural portmanteaus.

The idea of the group of people meeting at a single location & telling each other stories was already long a commonplace of literature, with Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (late 1300s) the hands-down classic of the form, & the first important supernatural example being Jan Potocki's of interlinking tales in, The Manuscript Found at Sargasso (1805).

Chaucerian examples were updated as a recurring method of connecting Victorian supernatural fiction, as in Jerome K. Jerome's Told After Supper (1891), or Robert Louis Stevenson's New Arabian Nights (1882).

The British portmanteaus it inspired especially in the '60s & '70s tended to be great fun but rather down-market from Amicus & Hammer, films like Twice Told Tales (1963), Dr. Terror's House of Horror (1964), From Beyond the Grave (1973), The Monster Club (1980), Tales from the Crypt (1972), Vault of Horror (1973), Tales that Witness Madness (1973), & a great many suchlike, not to mention non-supernatural portmanteaus such as O. Henry's Full House (1952).

Portmanteau horror sets continue to be filmed & are especially common from Japan. The J-horror examples tend again to be down-market in nature, Dark Tales of Japan (2004) just one example. But Masaki Kobayashi's Kwaidan (1964) is as arty-wonderful as arty gets. Portmanteau horror sets continue to be filmed & are especially common from Japan. The J-horror examples tend again to be down-market in nature, Dark Tales of Japan (2004) just one example. But Masaki Kobayashi's Kwaidan (1964) is as arty-wonderful as arty gets.

Dead of Night itself is rather a classy work. It boasts Georges Auric's dramatic score performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, lovely b/w cinematography, & several splendid character-actor performances.

It will be forever remembered for its unforgettable finale tale of The Ventriloquist Dummy starring Michael Redgrave, which far exceeds the other segments in sheer creepitude. But the whole film is grand, based on short stories, which I'll assess in detail.

As the wrap-around story for Dead of Night begins, Walter Craig (Mervyn Johns), an architect, arrives at a country house, where he's to stay the weekend. He's greeted at the gate by his host Mr Eliot Foley (Roland Carver), a potential client.

As the wrap-around story for Dead of Night begins, Walter Craig (Mervyn Johns), an architect, arrives at a country house, where he's to stay the weekend. He's greeted at the gate by his host Mr Eliot Foley (Roland Carver), a potential client.

He's soon introduced to his host's mother Lila Foley (Mary Merrall) the lady of the house who in turn introduces him to an array of guests who preceded him in arrival: Mrs. Joan Cortland (Googie Withers), psychiatrist Dr. Van Straaten (Frederick Valk), race car driver Mr. Hugh Granger (Anthony Baird), & teenager Sally O'Hara (Sally Ann Howes).

No one seems to notice Mr. Craig's in a bewildered state, looking about with eerie recognition of a residence he has to his knowledge never entered before.

"It isn't a dream this time," he observes. "I must be going out of my mind." He explains the group that he's dreamt about all of them time & time again, always right here in this room.

There's a sixth member of the group, however, who as he recalls arrives late. No one recognizes her by this discription of her as "a penniless brunette." There's a sixth member of the group, however, who as he recalls arrives late. No one recognizes her by this discription of her as "a penniless brunette."

Mr. Grainger is intrigued by the notion of knowing the future, & begins to tell a tale of a day he nearly died in a race track collision. As we go into the episode The Hearse Driver based on the short story "The Bus Conductor" (Pall Mall Magazine, December 1906) by famed ghost story writer E. F. Benson.

Virtually all reference works insist E. F. Benson also wrote the original short story upon which the wraparound story was based, but no such story has ever been named. I suspect it is original to the film, probably the combined effort of Angus MacPhail, John V. Baines & T. E. B. Clark, custom fit to make the five short stories seem of a single cloth.

In The Hearse Driver, Grainger awakens in the hospital, having been in a delirium for six days since the accident. In The Hearse Driver, Grainger awakens in the hospital, having been in a delirium for six days since the accident.

He has been in the care of Dr. Albury (Robert Wyndham) & nurse Joyce (Judy Kelly). He recovers over the next few days, during which time he falls in love with the nurse.

Sitting up in bed reading, he sees it's a quarter past four when he hears an odd sound outside in the driveway. He looks down from the window & sees an old-fashioned horse-drawn hearse. The driver (Miles Malleson) gazes up at him & says, "Just room for one inside sir!" When Grainger turns around it's only a little before ten at night.

Eventually he is fully recovered & leaves the care of his nurse & doctor. At exactly 4:15, when a doubledecker bus pulls up to a curb, & the conductor within says, "Just room for one inside, sir," Grainger, recognizes the man as the driver of the death-coach in his dream. He refuses to get on, & thus is his life saved.

The gathering at the country home discusses Grainger's story & its likelihood, the psychiatrist as yet a doubter, the others inclined to believe in such premonitions as more than coincidence.

The gathering at the country home discusses Grainger's story & its likelihood, the psychiatrist as yet a doubter, the others inclined to believe in such premonitions as more than coincidence.

About then the sixth member of the gathering arrives. She's Hugh Grainger's wife & former nurse Joyce, who asks her husband for money for the cabby's fare as she spent her last penny at the train station, which would make her "the penniless brunette."

The psychiatrist begins to suspect an elaborate practical joke at his expense, as he won't believe in the supernatural. Mr. Craig, however, insists that something horrible is pending. Sally then stands from her seat to say she once had such an experience, & so begins the tale of The Christmas Party.

This episode is always asserted to have been based on a story by Angus McPhail, though I've never been able to locate such a story. It may well be McPhail's original screenplay, or based on a story he never published. It may also just be misattributed, as the two stories ascribed to screenwriter John Baines were actually by E. F. Benson (The Haunted Mirror) & Gerald Kersh (The Ventriloquist's Dummy), while the wraparound story is attributed, wrongly I'm convinced, to Benson.

Whatever the case, McPhail & Baines were primary authors of the overall screenplay. Whatever the case, McPhail & Baines were primary authors of the overall screenplay.

McPhail is is best remembered as a Hitchcock screenwriter, & said to have been the original of Hitchock's "MacGuffin," the extra character of a tale of murder & suspense, who misdirects audience interpretation of clues. McPhail & John Baines co-wrote the screenplay for all the stories.

There's a gathering of fellow teenagers at a holiday party when the youths decide to play hide & seek in the mansion. Sally runs upstairs & hides behind the curtain of a narrow loft.

In this variant of the game, only one person hides, & each person who finds the hiding place hides in the same place until "we're packed in like sardines," the game ending when only one person is still searching.

A young man, Jimmy (Michael Allan), finds Sally in a nook behind a curtain. As they hide together, he tells her the house being haunted. "Everyone says so." But he doesn't reveal the specifics. Together they sneak out from behind the curtain because, says Jimmy, "I know a much better place," & into the cluttered attic they go.

In the attic, Sally finds a narrow servants corridor, & the young man does not see to where she disappeared. The corridor gains her access to a room below in which she hears weeping.

She finds a little boy, who feels better now that he has company, & introduces himself as Francis Kent, half-brother of Constance "who's all grown up now." Sally pities the lad, tucks him into bed, sings him a lullaby. "I wish you were my sister," says he. She finds a little boy, who feels better now that he has company, & introduces himself as Francis Kent, half-brother of Constance "who's all grown up now." Sally pities the lad, tucks him into bed, sings him a lullaby. "I wish you were my sister," says he.

Meanwhile the other teenagers have searched everywhere except the playroom, which the nanny keeps locked. Finally she returns to their accumulative relief, telling where she had been.

Only then is the story of the ghost in the locked room is soon revealed by Jimmy who had warned her the house was haunted. Francis was long ago murdered by his half-sister, as many Brits would've known at once since the murder by Constance Kent of her baby brother in 1860 was a well-known crime of popular imagination.

The case had also been an inspiration for portions of Wilkie Collins' classic The Moonstone (1868) & Charles Dickens The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), & many other novels & tales since, most recently Kate Summerscale's The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher (2008).

This episode was dropped from the initial American release of Dead of Night, as was The Golfing Story which is the fourth tale of the intact film.

Again the psychiatrist tries to explain away the ghost encountered by Sally. He insists Mr. Craig tell them more of his dream, in advance of it happening.

Again the psychiatrist tries to explain away the ghost encountered by Sally. He insists Mr. Craig tell them more of his dream, in advance of it happening.

Craig says that it's always hard to remember a dream, but he recalls hitting Sally rather savagely, & has already forwarned that Dr. Van Straaten will later break his glasses.

Joan Cortland believes in occult happenings, & wants to test the doctor's capacity for rationalizing things. She tells the story of something inexplicable that happened to her, & so begins the second-best story of the set, "The Haunted Mirror," which has long been misattributed as based on an orginal story by John Baines. It's really based on E. F. Benson's tale "The Chippendale Mirror" (Pearson's Magazine, May 1915).

When Joan & Peter Cortland (Ralph Michael) were still engaged, she bought him a gift, an antique mirror. Peter very soon begins to see in the mirror reflections of a completely different room, out of another era.

Joan thought Peter's preoccupation & nervousness was due to preparations for their marriage, but he finally he reveals to her that the mirror has been disturbing him a great deal.

He tries never to look in it at all, & yet it has a mesmeric power over him, as though the mirror were trying to draw him into that other room, or that his actual room is the imaginary one. But "if I cross the dividing line, something awful will happen," for something horrible awaits in that other room.

She wants to get rid of the mirror then, but he says, "The problem isn't with the mirror. It's in my mind," & he worries for his sanity, & thinks they should postpone the wedding. "Supposing I am going mad. Wouldn't be much for for you would it?" She wants to get rid of the mirror then, but he says, "The problem isn't with the mirror. It's in my mind," & he worries for his sanity, & thinks they should postpone the wedding. "Supposing I am going mad. Wouldn't be much for for you would it?"

But Joan won't hear of it & they soon marry & move into a house of their own. She wanted to get rid of the mirror, but he insisted they keep it in their new home. One week she leaves to visit her mother, & Peter's alone for the first time in weeks with the mirror, wlhich again begins to exert its influence over him.

Mrs Courtney meanwhile visits the antique dealer Mr. Rutherford (Esme Percy) where she obtained the mirror. His store has many of the objects from the room Peter had described. Rutherford explains that he obtained the entire content of a room that had remained locked since 1837, after the death of a morose madman who strangled his wife then cut his own throat before that mirror.

She returns at once from her trip to her mother's, to find her husband's personality changed. He's become insanely jealous, convinced his wife had actually gone away to be with a lover. He tries to kill her & she is able to save them both only by breaking the mirror.

"You poor darling," says Mrs. Grainger. The psychiatrist offers a medical explanation as improbable as the haunting itself. Mr. Craig meanwhile decides he wants to leave at once, as his dream was a warning to himself over something horrible waiting for him amidst this gathering.

"You poor darling," says Mrs. Grainger. The psychiatrist offers a medical explanation as improbable as the haunting itself. Mr. Craig meanwhile decides he wants to leave at once, as his dream was a warning to himself over something horrible waiting for him amidst this gathering.

The psychiatrist insists he stay, to overcome his obsession, or he will live forever a prisoner to delusion. But before he can get out, his friend Mr. Foley tells of the fate of a couple friends of his at his golfing club.

This is The Golfer's Story, about two friends divided by the arrival of a woman they both love. It is by far the weakest of the tales, & was deleted from the American release.

And yet it is most like the comedies that Ealing Studios would become most famed for, & for which the studio remains best remembered. Indeed the director of this episode Charles Crichton, also helmed the Ealing classic The Lavender Hill Mob (1951).

The Golfer's Story is based rather too losely on "The Story of the Inexperienced Ghost" (Strand Magazine, March 1902) by H. G. Wells.

They rivals decide to play a round of golf for Mary (Peggy Bryan), the loser to withdraw his attentions forever. Larry (Naunton Wayne) suspects George ( Basil Radford) cheated on a certain hole & is reluctant to concede defeat. Nevertheless, he turns about & walks into a lake until the water is above his head, & drowns himself.

Mary & Geroge have soon engaged. "With Mary in the bag," George thought it time to turn his mind to more serious things, meaning golf, which he had neglected ever since "the Potter tragedy" when Larry Potter strode calmly into the lake. Mary & Geroge have soon engaged. "With Mary in the bag," George thought it time to turn his mind to more serious things, meaning golf, which he had neglected ever since "the Potter tragedy" when Larry Potter strode calmly into the lake.

It is then that Eliot Foley joined George for a round, & became witness to the inexplicable.

At the lake George hears a voice: "Hello George old man. Still cheating?" The vengeful spirit completely ruins his game, in what amounts to a comedy haunting, interferring with George's swing & ball. At one point a golf ball circles the players' heads & returns to where George first hit it.

Later in the clubhouse, the ghost of his dead chum joins him at the bar, causing the bartender (Peter Jones) to think George is talking to himself. Larry promises to haunt him for life, unless he gives up Mary. He says he's willing to do that, but when he's told he must also give up golf, he won't do it.

He lied about giving up Mary in any case. The story continues in the comedic manner with Larry's spirit always nearby, making it impossible for George to consumate the marriage night.

Larry has grown rather ashamed of himself actually, but he's really forgotten how to dematerialize. A most unbelievable twist ending occurs. And it's clearly truly only a duffer's tall tale, a joke, which Eliot Foley told only because didn't want to be left out of the story-ring.

The fifth & final tale is by far the best, the reason Dead of Night is so lastingly remembered, even though there are a few critics across the decades who've argued that the tale of the haunted mirror is more powerful.

The fifth & final tale is by far the best, the reason Dead of Night is so lastingly remembered, even though there are a few critics across the decades who've argued that the tale of the haunted mirror is more powerful.

The Ventriloquist Dummy was loosely based on Gerald Kersh's equally horrifying tale "The Extraordinarily Horrible Dummy," though almsot invariably credited to screenwriter John Baines who only adapted the tale. The tale is in Kersh's collection The Horrible Dummy & Other Stories (Heinemann, 1944) but was earlier published with "Extraordinarily" in its title in the anthology Penguin Parade 6 (Penguin, 1939). A recognized classic, it can be found in numerous anthologies.

Kersh was perhaps never credited because Ealing Studios did not actually purchase the rights & hoped to slip it in unnoticed by the copyright owner, given the many changes of plot points & character names.

Kersh was not a steady man & may have been impossible to track down, or it may even have been known he'd been, if only temporarily, an army deserter & as the war was still on when this film was being written, he may have been intentionally slighted.

The lacking credit, however, is a terrible injustice. Kersh is otherwise well remembered as a great writer especially of macabre tales, but Dead of Night would have been one ofd the biggest feathers in his cap if only he'd been acknowledged.

"There was one occasion in my professional career that made me wonder" the psychiatrist admits, & there's an added irony that he of all people would be the one to give witness to the horrifying tale of The Ventriloquist Dummy. "There was one occasion in my professional career that made me wonder" the psychiatrist admits, & there's an added irony that he of all people would be the one to give witness to the horrifying tale of The Ventriloquist Dummy.

It regarded the case of the ventriloquist Maxwell Frere (Michael Redrave in a tremendous, nervous performance), imprisoned on charges of attempted murder. Dr. Van Straaten was brought in to assess Frere's mind, discovering him indeed unstable.

In a flashback within the flashback, we see Maxwell & Hugo's comedy act in dinner club. Hugo is the dummy, & they're pretty pretty darned entertaining, as Hugo seems always to be the one in charge of the act.

At one point of the act seems to have gotten out of Maxwell's control entirely, when Hugo refuses to sing on cue. The dummy only wants to talk to talk to a certain audience member, Sylverster Kee (Hartley Power), an American ventriloquist who dropped into the club.

Hugo persists in his assertion he'd rather work with Kee, being about done with the old hack Maxwell. The more uncomfortable Max seems to be, the funnier the audience finds it, though it's beginning to look like an authentic battle of wills right in front of the audience.

When they leave the stage, the club band plays the tropical jazz number "The Hullalooba" with Sylvester's friend & the niteclub's owner, Beaula, as singer. The song was written by Anna Marly & the band is the Frank Weir Sextet. When they leave the stage, the club band plays the tropical jazz number "The Hullalooba" with Sylvester's friend & the niteclub's owner, Beaula, as singer. The song was written by Anna Marly & the band is the Frank Weir Sextet.

Weir was a well-known British saxophonist & swing-band leader throughout the 1940s & '50s.

Playing Beaula is American singer Elisabeth Welch who, like many African Americans, went to Europe where racism also existed but wasn't quite so dead-set on keeping entertainers from getting good work. She starred opposite Paul Robeson in British-produced Song of Freedom (1936) & Big Fella (1937)

Sylvester Kee heads back stage & ends up in a business discussion with Hugo, startled that Max seems to be throwing his voice from a completely different room. Sylvester thinks he's just going along with a joke, but Max is becoming increasingly paranoid that Hugo will leave him.

He angrily kicks Sylvester out of the dressing room, by which time it's fairly obvious Max isn't dealing from a full deck. "Take me with you! Maxwell let go of me!" Sylverster flees, convinced Maxwell is a complete nutter.

As played, there appears to be a very good chance but that Hugo moves, speaks, even bites of his own will, though there's even less question that Max is losing his mind, so certainly could be persecuting himself through his ventriloquist skills. As played, there appears to be a very good chance but that Hugo moves, speaks, even bites of his own will, though there's even less question that Max is losing his mind, so certainly could be persecuting himself through his ventriloquist skills.

Hugo is only barely deniable as a demonic presence of some sort, but either way, he's menacing & creepy, while poor Max is helpless.

Over time, Hugo becomes more & more impossible to restrain. Yet Max can't bare to be without him, even when not on stage.

Even on a drunken binge, he keeps Hugo with him. Hugo incredibly enough remains sober as alcoholic Max descends into a barely comprehending state. And so Hugo easily gets Max in trouble, casting insults around the coctail lounge, Max all but catatonic.

When Hugo goes missing, Max tracks down Sylvester Kee who had nothing to do with it. And yet Hugo was indeed secreted away in Kee's room, & Max draws a gun & shoots his feared rival point blank.

Now imprisoned for attempted murder, Dr. Van Straaten has Hugo brought to Maxwell for the final interview, believing as he does that Max will never tell the truth, may not even know the truth, unless he speaks it through Hugo. Now imprisoned for attempted murder, Dr. Van Straaten has Hugo brought to Maxwell for the final interview, believing as he does that Max will never tell the truth, may not even know the truth, unless he speaks it through Hugo.

Hugo brags to Max that Sylvester is recovering & he'll soon be needing a new partner. "They'll put you in the madhouse. But not little Hugo. I'll team up with Sylvester. Maybe we'll come & see you."

This is a deeply disturbing tale. The final scene of "murdering" Hugo is one of the craziest things ever filmed, & as if that weren't climax enough, it is followed by an absolutely shocking afterward defining Maxwell's extraordinary madness in the most chilling terms.

One might suppose that after the gutwrenching conclusion to The Ventriloquist Dummy the wraparound story would just make some droll observation & credits would role.

One might suppose that after the gutwrenching conclusion to The Ventriloquist Dummy the wraparound story would just make some droll observation & credits would role.

And yet the tale of Walter Craig's recurring nightmare turns out to be more than an excuse to string together diverse tales.

It concludes as a tremendous piece of horror patterned on German Expressionist cinema. The use of shadow is advanced film noir atmospherics; the pacing is ferocious in rapidity; with angles & architecture that take some cues from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

When the primary stories are told, with Walter Craig's prophetic mutterings about his recurring dream indeed coming true, he stammers with increasing craziness, lamenting: "If only I had left here when I wanted to!" He perpetrates an act of murder, then flees into a surrealist environment.

The bizarre summation brings all the disparate story-parts together in an experimental conclusion conveying unutterable madness, the highlight of which is the return of Hugo as a fully ambulatory creature (otherwise unknown dwarf actor John McGuire plays Hugo at this point).

At the height of surreal menace, Craig is awakened by his wife (Renee Gadd), having been in the thros of a nightmare. The pace "calms" into a finale worthy of Rod Serling as Craig takes a phone call from one Eliot Foley, who invites him to stay a weekend at Pilgrim's Farm to assess planned renovations. "I wonder why that sounds so familiar?" he asks himself, having forgotten his dream.

Continue to the next ventriloquist dummy:

Magic (1978)

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

Dead of Night (1945) is one of the earliest horror-omnibus or anthology films. It tells five short tales with four different directors, expertly & smoothly knitted together by a sixth tale, the wraparound narrative. Such films are sometimes called "portmanteaus" after a travel-trunk holding odds & ends.

Dead of Night (1945) is one of the earliest horror-omnibus or anthology films. It tells five short tales with four different directors, expertly & smoothly knitted together by a sixth tale, the wraparound narrative. Such films are sometimes called "portmanteaus" after a travel-trunk holding odds & ends. Even though not "first," Dead of Night would be the most important in establishing a veritable sub-genre of supernatural portmanteaus.

Even though not "first," Dead of Night would be the most important in establishing a veritable sub-genre of supernatural portmanteaus. Portmanteau horror sets continue to be filmed & are especially common from Japan. The J-horror examples tend again to be down-market in nature,

Portmanteau horror sets continue to be filmed & are especially common from Japan. The J-horror examples tend again to be down-market in nature,

There's a sixth member of the group, however, who as he recalls arrives late. No one recognizes her by this discription of her as "a penniless brunette."

There's a sixth member of the group, however, who as he recalls arrives late. No one recognizes her by this discription of her as "a penniless brunette." In The Hearse Driver, Grainger awakens in the hospital, having been in a delirium for six days since the accident.

In The Hearse Driver, Grainger awakens in the hospital, having been in a delirium for six days since the accident. The gathering at the country home discusses Grainger's story & its likelihood, the psychiatrist as yet a doubter, the others inclined to believe in such premonitions as more than coincidence.

The gathering at the country home discusses Grainger's story & its likelihood, the psychiatrist as yet a doubter, the others inclined to believe in such premonitions as more than coincidence. Whatever the case, McPhail & Baines were primary authors of the overall screenplay.

Whatever the case, McPhail & Baines were primary authors of the overall screenplay. She finds a little boy, who feels better now that he has company, & introduces himself as Francis Kent, half-brother of Constance "who's all grown up now." Sally pities the lad, tucks him into bed, sings him a lullaby. "I wish you were my sister," says he.

She finds a little boy, who feels better now that he has company, & introduces himself as Francis Kent, half-brother of Constance "who's all grown up now." Sally pities the lad, tucks him into bed, sings him a lullaby. "I wish you were my sister," says he. Again the psychiatrist tries to explain away the ghost encountered by Sally. He insists Mr. Craig tell them more of his dream, in advance of it happening.

Again the psychiatrist tries to explain away the ghost encountered by Sally. He insists Mr. Craig tell them more of his dream, in advance of it happening. She wants to get rid of the mirror then, but he says, "The problem isn't with the mirror. It's in my mind," & he worries for his sanity, & thinks they should postpone the wedding. "Supposing I am going mad. Wouldn't be much for for you would it?"

She wants to get rid of the mirror then, but he says, "The problem isn't with the mirror. It's in my mind," & he worries for his sanity, & thinks they should postpone the wedding. "Supposing I am going mad. Wouldn't be much for for you would it?" "You poor darling," says Mrs. Grainger. The psychiatrist offers a medical explanation as improbable as the haunting itself. Mr. Craig meanwhile decides he wants to leave at once, as his dream was a warning to himself over something horrible waiting for him amidst this gathering.

"You poor darling," says Mrs. Grainger. The psychiatrist offers a medical explanation as improbable as the haunting itself. Mr. Craig meanwhile decides he wants to leave at once, as his dream was a warning to himself over something horrible waiting for him amidst this gathering. Mary & Geroge have soon engaged. "With Mary in the bag," George thought it time to turn his mind to more serious things, meaning golf, which he had neglected ever since "the Potter tragedy" when Larry Potter strode calmly into the lake.

Mary & Geroge have soon engaged. "With Mary in the bag," George thought it time to turn his mind to more serious things, meaning golf, which he had neglected ever since "the Potter tragedy" when Larry Potter strode calmly into the lake. The fifth & final tale is by far the best, the reason Dead of Night is so lastingly remembered, even though there are a few critics across the decades who've argued that the tale of the haunted mirror is more powerful.

The fifth & final tale is by far the best, the reason Dead of Night is so lastingly remembered, even though there are a few critics across the decades who've argued that the tale of the haunted mirror is more powerful. "There was one occasion in my professional career that made me wonder" the psychiatrist admits, & there's an added irony that he of all people would be the one to give witness to the horrifying tale of The Ventriloquist Dummy.

"There was one occasion in my professional career that made me wonder" the psychiatrist admits, & there's an added irony that he of all people would be the one to give witness to the horrifying tale of The Ventriloquist Dummy. When they leave the stage, the club band plays the tropical jazz number "The Hullalooba" with Sylvester's friend & the niteclub's owner, Beaula, as singer. The song was written by Anna Marly & the band is the Frank Weir Sextet.

When they leave the stage, the club band plays the tropical jazz number "The Hullalooba" with Sylvester's friend & the niteclub's owner, Beaula, as singer. The song was written by Anna Marly & the band is the Frank Weir Sextet. As played, there appears to be a very good chance but that Hugo moves, speaks, even bites of his own will, though there's even less question that Max is losing his mind, so certainly could be persecuting himself through his ventriloquist skills.

As played, there appears to be a very good chance but that Hugo moves, speaks, even bites of his own will, though there's even less question that Max is losing his mind, so certainly could be persecuting himself through his ventriloquist skills. Now imprisoned for attempted murder, Dr. Van Straaten has Hugo brought to Maxwell for the final interview, believing as he does that Max will never tell the truth, may not even know the truth, unless he speaks it through Hugo.

Now imprisoned for attempted murder, Dr. Van Straaten has Hugo brought to Maxwell for the final interview, believing as he does that Max will never tell the truth, may not even know the truth, unless he speaks it through Hugo. One might suppose that after the gutwrenching conclusion to The Ventriloquist Dummy the wraparound story would just make some droll observation & credits would role.

One might suppose that after the gutwrenching conclusion to The Ventriloquist Dummy the wraparound story would just make some droll observation & credits would role.