On a forested back road, three young men are pursued by the titular Black Cadillac. This purports to be a thriller but every minute of it is just so obvious. It tries to pump up its merits by pretending it is a true story that happened in 1983, but it's more like a self-agrandizing shaggy dog story drunks tell each other. On a forested back road, three young men are pursued by the titular Black Cadillac. This purports to be a thriller but every minute of it is just so obvious. It tries to pump up its merits by pretending it is a true story that happened in 1983, but it's more like a self-agrandizing shaggy dog story drunks tell each other.

There is no plot to speak of. We don't get to find out until the end why the boys are being pursued, but it's no surprise, it's simply a matter of the villain's jealous rage, big wup.

Because as "mystery" or "suspense" it has none, it was marketed as a horror film promising only a big black menacing 1957 Fleetwood Caddy.

The advertising leads one to expect Christine (1983) or The Car (1977) but it's more like having a film about hillbilly psychopaths with such small personalities that what they're driving counts for more than their characterizations. Neither the car nor who's driving it have any mystery or complexity.

Randy Quaid as the cop is pretty good at being ambiguous, but as his character progresses he becomes less rather than more interesting. The three young men are cyphers -- nerd, jock, & rebel -- & only Josh Hammond as the scar-faced C.J. brings any life to his cypher, in part by imitating a young Jack Nicholson. Randy Quaid as the cop is pretty good at being ambiguous, but as his character progresses he becomes less rather than more interesting. The three young men are cyphers -- nerd, jock, & rebel -- & only Josh Hammond as the scar-faced C.J. brings any life to his cypher, in part by imitating a young Jack Nicholson.

Shane Johnson plays Scott, the jock with a secret that's totally transparent so it's stupid to not reveal it until the end (what the hell, I'll reveal it now -- he scarred C.J. when they were in junior highschool). He's not a bad actor, but the role is written very badly & he's not genius enough to sell such weak stuff.

Jason Dohring is Scott's envious nurdy brother who grew up in the shadow of his successful jock bro'. It's another one-note character well enough played but not well enough written. He keeps asking C.J. how he really got scarred, as C.J. only tells Tall Tales about how it happened.

In one of the script's many lapses in continuity & internal logic, we learn that Scott's family, which would include Robbie, always believed C.J. got hurt in a bicycle accident. There's no reason Robbie wouldn't remember the catastrophic day that Scott's best friend was rushed to the hospital, yet it's all news to him when revealed at the end. It's almost like Robbie was made Scott's brother as an afterthought, & the character still had most of the early-draft assumptions that he hadn't known Scott his whole life.

The ending requires a cliff to suddenly appear. When the boys' Saab finally dies on the lake ice & they run off into the woods hoping to save C.J., there is no cliff, hill, or mountain climbing sequence. But at the last possible minute the black Caddy drives off a cliff & plunges through the lake ice far, far below. It was just the final insult to injury in what was over all a stupid script stupidly filmed & acted with moderate competence but barely worthwhile.

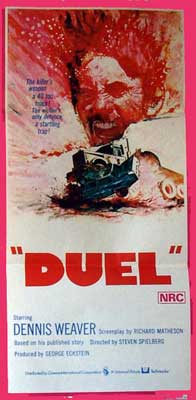

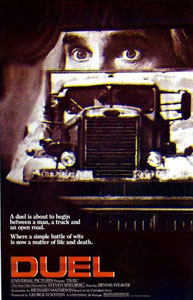

Pretty much the same story was done vastly better as a made-for-tv film in 1971. Duel was intended as a major-film release to star Gregory Peck, but when Peck turned it down, it was produced as a telefilm with Steven Spielberg directing early in his career. Pretty much the same story was done vastly better as a made-for-tv film in 1971. Duel was intended as a major-film release to star Gregory Peck, but when Peck turned it down, it was produced as a telefilm with Steven Spielberg directing early in his career.

Spielberg, a film school dropout, had very little experience & none of the power he would later possess to make & choose his own projects, but he unofficially read the script, fell in love with it, & began begging for the assignment.

Based on a short story by Richard Matheson that originally appeared in Playboy, & adapted by Matheson himself, it just started out with a marvelous script.

Many believe it's the film that sparked the early '70s craze for horror-tinged thrillers, including Spielberg's Jaws (1975), as well as a whole spate of telefilm grotesques.

The original cut seen on television was 74 minutes. It was released theatrically in Europe, with new scenes hastily shot by Spielgberg -- school bus sequence, railroad track sequence, telephone booth scene-of-destruction -- to bring it to 90 minutes. A bit of cussing was looped in as well.

Dennis Weaver plays to perfection a milquetoast businessman crossing the lonesome desert when a psychotic truck driver begins to play a terrifying game of cat & mouse between automobile & 40 ton truck (a 1955 Peterbilt). The driver is never seen.

The film is a riot of tiny errors like the multiple times we see into Weaver's rear view mirror & catch glimpses of the film crew. But even with no budget to reshoot the mistakes & a truckload of continuity gaffs which make Duel in part a "find the booboo" puzzle, this film even so just never stops being edgy & creepy. The film is a riot of tiny errors like the multiple times we see into Weaver's rear view mirror & catch glimpses of the film crew. But even with no budget to reshoot the mistakes & a truckload of continuity gaffs which make Duel in part a "find the booboo" puzzle, this film even so just never stops being edgy & creepy.

The anonymity of the driver is one of the reasons this film works. The "why" of it is not half so interesting as the fact that there is no reason.

It is an irresolvable mystery, like death itself, that makes Duel, Christine & The Car effectively horrific. If it had been all the machinations of a jealous husband as in Black Cadillac, it would have no power at all.

In the short story, terrorized David Mann finally just gives up, his car is dead, he sits in it watching the truck barrelling down on him, & only by great good fortune does the truck inexplicably wobble & fall over a cliff. Matheson rethought the ending in the meantime & has Weaver an active participant in his own salvation.

Though Duel has a deceptive simplicity & economy, if it were really as simple as being one long car chase, it could not possibly have evaded tedium. It certainly helps that Spielberg came up with some suprising camera work that kept it from looking too much like a cheap telefilm, but in the main it never loses intensity because it is infused with a genuine mysteriousness.

On the surface it is a literal story of a truck driver gone insane. On another level it is symbolic of Mann's smallness in a terrifying world, & defeating the bohemoth truck could well be a changing point in Mann's downtrodden life; in this context even the hero's name "Mann" is symbolic. On the surface it is a literal story of a truck driver gone insane. On another level it is symbolic of Mann's smallness in a terrifying world, & defeating the bohemoth truck could well be a changing point in Mann's downtrodden life; in this context even the hero's name "Mann" is symbolic.

On yet another level, there may not really be any truck. In the scene with the bus driver on the same road, the bus driver states that he never saw any truck, so Mann doubts his own sanity. In the original short story Mann is more completely the only person who has any experience with it, & in the end it more or less just vanishes of its own accord while Mann waits passively for annihilation.

In the film, though, evidence is definitely in favor of the truck existing, but that edge of impossibility is there. There are just so many layers to Matheson's story that were by no means lost in the film adaptation.

I've forever since gotten the creeps on cross-country drives whenever a big truck appears in my rear view mirror. Once in the pitch dark driving through the midwest, my girlfriend & I experienced an actual psycho truck driver who dealt with the boredom of his job in a novel manner: He drove up as close behind our little green Volkswagon as he could get & then suddenly turned on about fifty blinding floodlights. I drove on the curb to let him pass, & as he roared off into the night, he turned on another fifty floodlights mounted on the back of his truck specifically to blind drivers behind him.

So what Matheson imagined is a real type of truck driver, & in fact his inspiration was a similar experience he'd had very similar to mine. Duel's closeness to the truth is another of the reasons it's so damned creepy: long distance truck drivers are bug-ass. So what Matheson imagined is a real type of truck driver, & in fact his inspiration was a similar experience he'd had very similar to mine. Duel's closeness to the truth is another of the reasons it's so damned creepy: long distance truck drivers are bug-ass.

It's also a fact that Spielberg has never made a better film. Bigger films sure, glossier films, vastly more commercial films & FX-driven films, but never a better film.

Japanese director Takeshi Miike claims he made so many of his films rapidly because he was aware that no director remained great after his thirties, & he wanted to finish as much as he could before he reached his forties & his artistic ability evaporated.

I always thought Miike was nuts to believe that, & wonder if he still believes it now that he's over forty. But for Spielberg, despite massive commercial success, he never came closer to achieving a moment of art than when directing Duel in his mid-twenties, so maybe Miike is onto something.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|