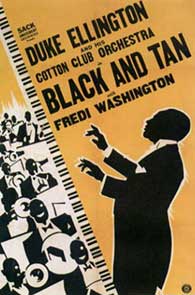

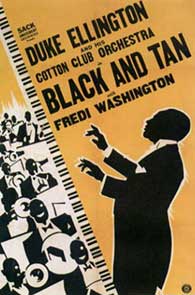

From Duke Ellington's Cotton Club days, the early sound film Black & Tan (1929) was a first-rate way to show off sound film technology as being so consequential it could bring performances of just this magnitude to any theater.

From Duke Ellington's Cotton Club days, the early sound film Black & Tan (1929) was a first-rate way to show off sound film technology as being so consequential it could bring performances of just this magnitude to any theater.

It was Duke's first film, made on the same sets & with the same crew with overlapping schedules, with Bessie Smith's film St. Louis Blues (1929).

The film doesn't shy away from such realities of the era as the Cotton Club having gangster investors, or black entertainers filling the stage, with black workers in the kitchen, but no African Americans were allowed to be served in the whites-only restaraunt.

Because it's such an early sound film, viewers today may find the sound quality disappointing, but to me it was tremendous to see the actual performance & the music is just so good the quality makes it through. I've put up with worse recorded sound than this by a long shot.

Stories aren't usually important in the short musical performance films, though little "excuses for plot" are frequently included. This one's a lot more tragic than would be seen in the jazz films of the following decade. And although everyone is ostensibly playing themselves & do not have fictional character names, the frame story is only a tearjerker work of fiction.

The orchestra performs with a dancer, Fredi Washington. She's playing Duke's wife, too, but in real life she would (in 1933) marry Duke's trumbonist Lawrence Brown.

The band's dancer has achieved a fame beyond that of the band. Without her star presence, the band might not get the pending contract which pretty much hinges on the club getting Fredi at the same time.

Alas, she has a heart condition & has been warned to give up her career. But Fredi can't let Duke down, & assuring Duke she's healthy enough to perform, she will literally dance herself to death.

This was Fredi's first film role & by rights she should've become a big star except for Hollywood racism. This was Fredi's first film role & by rights she should've become a big star except for Hollywood racism.

In real life, she had been told by Hollywood promoters that if she'd be willing to hide her black identity, she could become a star as big as Gretta Garbo. She not only refused, but involved herself in establishing the Negro Actors Guild.

Her biggest role was as Peola in Imitation of Life (1934), in which she plays a woman passing for white, who must turn her back on her own good kind mother to perpetuate the ruse. The role unfortunately defined her for many people, & she was often confronted by people of both races who thought she, like Peola, wished to turn her back on her heritage.

Her career had many early highlights as a dancer on Broadway & top stages of London, Paris, & Berlin. Yet her film career never got as far, because the doors that were opened to black women in those days needed their coloring to be just a little darker -- not too dark, but not ambiguous either.

A civil rights activist herself, it's a frightful irony that being black made her unacceptible for better roles in white-dominated filmmaking, but looking more Latina than Negro got her passed over for black roles. She did have a very few good roles in the 1930s opposite Paul Robeson in The Emperor Jones (1933) & Bill Bojangles Robinson in One Mile from Heaven (1937), but ultimately her complete filmography would remain small.

The early scenes of Black & Tan encompass a comedy routine that for the minimal plot establishes that Duke's band isn't getting the bookings it needs & Duke is on the verge of having the piano in his apartment repossessed for failure to make payments.

The early scenes of Black & Tan encompass a comedy routine that for the minimal plot establishes that Duke's band isn't getting the bookings it needs & Duke is on the verge of having the piano in his apartment repossessed for failure to make payments.

The two comics who arrive as piano movers are playing the type of stupid, illiterate, childlike black men that are too stereotyped to be funny nowadays, & they are the greatest drawback for the film.

This comic character type is universal & essentially the same as are played by white guys in Dumb & Dumber (1994). If these guys did their schtick at the Apollo Theater for an all-black audience it might have no worse connotations than when Jim Carey plays such characters today. Still, in later films, Ellington had more personal input, & kept such stereotyped characters out of the mix.

Yet it can't have been easy for an openhearted guy like Ellington to pass judgement on these old-style minstrel-show comics. The shorter guy is Frankie Half-Pint Jaxon, who did his cornpone black-hillbilly routines to warm up audiences for the likes of Ethel Waters & Bessie Smith, whose stage shows he helped design.

How do you tell such a beloved pioneer that his humor doesn't project the right image to be seen in middle America? That Half-Pint dropped out of show business in the early 1940s probably had everything to do with the rise of Civil Rights leaders who unlike Duke didn't care what such entertainers lived through to achieve any degree of success; & they stamped the Stepin Fetchit brand of humorists out of existence, stigmatizing the performers themselves.

Duke gave Half-Pint national exposure with this film, & it would've been a tragedy to regret doing so. Still, I must admit, even a mood of forgiveness, I would rather have seen Half-Pint performing one of his comedy musical bits, not his igger'nt darkie bit.

As an aside, the two piano movers are often alleged to be Alec Lovejoy & Edgar Connor. As the short guy is without question Half-Pint, & there are only two movers, they can't be Lovejoy & Connor, though the remaining guy might be Lovejoy, whose large size was paired with Half-Pint for the exaggerated effect of their differential.

In the context of this short-subject tragedy, Duke Ellington & His Orchestra perform at least three original compositions.

In the context of this short-subject tragedy, Duke Ellington & His Orchestra perform at least three original compositions.

"The Duke Steps Out" is played as a dirge-march reminiscent of Cab Calloway, & includes a stunning trumpet solo by Arthur Whetsel, Duke's real-life pal since college days.

On the Victor recording, it was Bubber Miley doing the trumpet solo rather than Whetsel. Nor is it played as a dirge. But I really like the film's slower version.

"Black Beauty" is the number for Fredi's main dance, which I've seen faulted by some commentators for failing to be a sexy dance. I think she's amazing, but she's not vamping it up for sex appeal, even allowing that there's an up-the-crotch shot taken as though from underneath a glass floor.

Rather, she's dancing like a wound-tight highly articulated doll, an "eccentric" dance such as were all the rage in Harlem of the 1920s, & which has its best film documentation at the end of Ellington's best film, Symphony in Black (1935) when Ernie Snakehips Tucker exaggerates the eccentric-dance beyond the eccentric.

The film is framed front & back with "Black & Tan Fantasy." Ellington always kept arrangements fresh & performers who were with him for decades said they never got tired of playing the same songs night after night because Duke never let the material become stale or too famililar. The film's arrangement of "Black & Tan Fantasy" is thus quite different from other recordings, this being the only version to add a clarinet solo for Barney Bigard.

Better ears than mine should also detect fragments of "Cotton Club Stomp," "Hot Feet" & "Same Train" worked into the arrangements. Lastly, the Hall Johnson Choir puts in a gospel moment at the end, for the sadness of Fredi's dying.

Hall Johnson was vocal coach to such great singers as Marian Anderson & Harry Belafonte, & his choir can be seen or heard in such films as Green Pastures (1933), Cabin in the Sky (1943), Dumbo (1940), & in the "scarecrow" segment of the anthology film Tales of Manhattan (1942).

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|