British film pioneer George Albert Smith (1864-1959) had gained a small fame in the 1880s as a hypnotist & magician, & convinced the easily duped Society for Psychical Research that he practiced authentic telepathy.

British film pioneer George Albert Smith (1864-1959) had gained a small fame in the 1880s as a hypnotist & magician, & convinced the easily duped Society for Psychical Research that he practiced authentic telepathy.

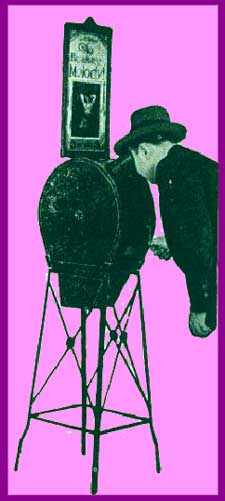

Then in 1894 opened an advanced-for-its-day magic lantern theater in Brighton which projected images with moving sections onto a screen to tell a story or recreate a magical effect, advertised as "High Class Lecture Entertainments with Magnificent Lime-Light Scenery and Beautiful Dioramic Effects."

"Dissolving effect" lanterns were complicated projectors difficult to master, but for someone with the skills like until a musician's to make it work, the effect of animation could be achieved even before motion picture film existed. Stories that had already become standard from static magic lantern slides he was adapting to the more complex system that mixed still slides with slides that had the capacity for dissolve & supplant components that gave the illusion of motion.

Keeping abreast of rapidly changing technology, G. A. Smith bought his first motion picture camera in 1896 & within the year was producing his own short films, frequently starring his wife Laura Bayley who helped develop the stories. She already had a reputation as a London comedy pantomime artist & brought all her skills to bare on the new medium as a comedy film actress.

Smith drew around him & encouraged other East coast inventors & filmmakers, & distributed their films internationally along with his own. This circle included Arthur Melbourne Cooper, Esme Collins, James Williamson, Alfred Darling & William Friese-Greene.

"Phantom Ride" films were movies shot from the front of a train with no sense of who could have such a point of view. Cecil Hepworth had made such a film, View from an Engine Front -- Train Leaving Tunnel (1898), which consisted of two shots made continuous by a moment of darkness representing the entry into the tunnel.

"Phantom Ride" films were movies shot from the front of a train with no sense of who could have such a point of view. Cecil Hepworth had made such a film, View from an Engine Front -- Train Leaving Tunnel (1898), which consisted of two shots made continuous by a moment of darkness representing the entry into the tunnel.

G. A. Smith staged & filmed an event he imagined occurring inside a passenger car of that very train. He spliced his own new footage this into the center of Hepworth's film, giving it greater context & humorous meaning.

So as The Kiss in the Tunnel (1899) opens, the unseen photographer rides on the front of the train toward a two-track tunnel. A train comes rushing out of the tunnel, as our point of view rider passes the opposite direction toward the tunnel.

The screen goes black as the train enters the tunnel, then the scene cuts to the lit inside of a passenger car. A gentleman (it's director G. A. Smith) is seated facing a lady (Laura Bayley). He begins teasing & kissing her while they're inside the tunnel, but quites as soon as the train leaves the tunnel.

The scene then cuts to the outside, as the light at the tunnel's end is reached. That's all there is to the film, just kisses given while in the tunnel. Yet in this his first film G. A. Smith had lit upon techniques of editing & continuity later filmmakers would take for granted.

For early filmmakers, anything the least bit novel or new would be emulated very closely by rivals, & it was only a matter of weeks before another filmmaker recreated Smith's film using a different angle to show the outside of the train & having a lower class couple instead of a middle class couple inside the passenger car, giving it the same title, The Kiss in the Tunnel (1899).

A rather different jest was developed for pretty much the same scenario in What Happened in the Tunnel (1903) when the masher finds he's kissed entirely the wrong woman while in the dark of the tunnel, or Love in a Railroad Train; aka, Love in a Train (1902) in which train comes back into the light revealing to the masher that he's kissing not the nanny, but the behind of the baby she cares for.

A host of similar films all drew on G. A. Smith's editing technique to convey the same jest or variant thereon. But it's the technique rather than the copied content that makes Smith's film so influential. When the technique seeped out into the entire film industry, the lasting influence of Smith's editing & continuity ideas would be less obviously derived from that first film informing film, though in a sense his The Kiss in the Tunnel is part of cinema right to the modern age.

Grandma (Catherine Cooper, the filmmaker's mother) is seated at a table. Her grandson Willie (Bert Massey) stands beside the table in the opening shot of Grandma's Reading Glasses (1900). The scenario was filmed by Arthur Melbourne Cooper (1874-1961) at St. Albans & distributed by G. A. Smith who is frequently credited as its director.

Grandma (Catherine Cooper, the filmmaker's mother) is seated at a table. Her grandson Willie (Bert Massey) stands beside the table in the opening shot of Grandma's Reading Glasses (1900). The scenario was filmed by Arthur Melbourne Cooper (1874-1961) at St. Albans & distributed by G. A. Smith who is frequently credited as its director.

Cooper had arranged his first "paying public" demonstration of motion pictures on December 18, 1895 in North Mymms, Hertfordshire, a full ten days earlier than the Lumiere's more famous first public film demonstration in Paris. Though Cooper would not ultimately make a great many films, those he did make hold historical significance, including the innovative Grandma's Reading Glasses.

The glasses are really only a magnifying glass, & Willy begins sorting through the objects in a box Grandma has set on the table. He looks at objects on & near the table through the huge magnifying glass, pictured through a circular cut-out to give the imrpession of the magnifying lense.

He looks at the insides of a pocket watch, then he turns to the canary in a hanging cage & looks at it through the lens, again shown through the circular cut-out. He looks at the insides of a pocket watch, then he turns to the canary in a hanging cage & looks at it through the lens, again shown through the circular cut-out.

Willie also looks at Grandma's right eye which appears enormous on the screen in the circle, then at the face of a cat.

In its primitive manner, the film is an early example of "point of view." The objects shown as though through something circular captures what Willie is looking at, which would not be the same size seen by Grandma, so the point of view is particular & specific.

The camera has ceased to be, as it often was in the earliest days of cinema, a distant dispassionate eye. It has become the eye of the protagonist. This is also the first film in which close-ups were intercut into a narrative film.

It was remade in America by American Mutoscope & Biograph as Grampa's Reading Glass (1902) in which a small girl instead of a boy looks through the magnifying lens.

G. A. Smith was a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society & all his interests would in one way or another lend to his filmmaking.

G. A. Smith was a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society & all his interests would in one way or another lend to his filmmaking.

In As Seen Through a Telescope (1900), the same trick of establishing point of view shots first seen in Grandma's Reading Glasses is done with a gentleman standing outside a shop with a two-foot telescope.

He is looking at the foot of a woman bicyclist, whose boyfriend or husband is helping repair a sandle strap that has come loose, as she holds her skirt up & out of the way.

When the couple is finished, the peeping tom sits down on a stool & pretends he wasn't doing anything untoward. As the woman & man walk by pushing the bicycle, the man gives the peeper a shove from behind, & he tumbles off his stool.

Smith has been given undue credit for innovating the close-up & point-of-view shot because of this film & Grandma's Reading Glasses, though it is now understood to have first been Arthur Melbourne Cooper innovation. As the two film pioneers were friends they were exchanging ideas rapidly.

The point-of-view close-up with circular cut-out is taken to comical extreme in James Williamson's The Big Swallow; aka, The Photographic Contortion (1901).

The point-of-view close-up with circular cut-out is taken to comical extreme in James Williamson's The Big Swallow; aka, The Photographic Contortion (1901).

An antic young man is standing in front of the camera, apparently complaining to the cameraman observing him through the camera aperature.

Williamson's 1901 catalog provides dialogue for the complainer, who is saying, "I won't! I won't! I'll eat the camera first." The actor is Sam Dalton, a profesional commedian of the era who apepars in other of Williamson's films as well.

The subject of the photograph does not want to have his picture taken. Instead of just getting out of the way of the lens, he saunters ever more closer to the lens, until his mouth is so big he can open it & bite onto the lens.

We then jump-cut to a shot of the cameraman with his head underneath a cloth. He is suddenly pulled into the camera, his feet vanishing last, as he is devoured by his subject! The final shot is of the subject backing away from the camera lens, his mouth becoming smaller & smaller, as he smacks his lips with satisfied appetite.

Very silly, & still amusing after more than a century, the historical significance of the film is that it is the first example of a narrative film that makes a distinction between the "camera's eye" with camera man looking at the subject, & the "audience eye" when we observe the cameraman being swallowed without reference to a second cameraman.

A classic Hans Christianson story was adapted by pioneering British filmmaker James Williamson in The Little Match Seller (1902), aiming at the opposite end of the emotions that The Big Swallow aimed for.

A classic Hans Christianson story was adapted by pioneering British filmmaker James Williamson in The Little Match Seller (1902), aiming at the opposite end of the emotions that The Big Swallow aimed for.

It begins with the heroine in the snowy street unsuccessfully trying to sell matches. She expresses misery even before a boy pelts her with snowballs & pedestrians ignore her imploring efforts.

At last she strikes a match in an attempt to warm her freezing hands, & the wall she is kneeling near seems to become a window revealing scenes of joy. Each time she strikes a match she has a different vision, of a warm hearth, of a table set with a holiday dinner, of a candle-lit christmas tree, a falling star, loving arms reaching out to her.

She leans back & falls into slumber, the snow gathering upon her. An angel appears over her, bends down to assist her spirit in leaving the body, & lifts her up to heaven. A passing police officer finds her pitiful corpse before the night is over.

A film called The Little Doctors (1901) apparently does not survive, but we kind of have it anyway, as it had a scene for scene remake as Sick Kitten (1903), both by G. A. Smith. Successful films were often remade when the negative of the original began to wear out from having so many prints struck. The Little Doctors

A film called The Little Doctors (1901) apparently does not survive, but we kind of have it anyway, as it had a scene for scene remake as Sick Kitten (1903), both by G. A. Smith. Successful films were often remade when the negative of the original began to wear out from having so many prints struck. The Little Doctors

A little girl in a chair is playing nurse to a kitten as though it were her infant child. A tiny boy in his father's tophat enters the frame, playing the doctor making a housecall.

The camera cuts to a close up of the little girl giving the kitten medicine from a spoon, which the kitten seems to enjoy. This having been done on the little doctor's advice, the girl thanks him, & he, with a tip of his hat & a bow to the camera, prepares to leave.

An amusing wee film with surprisingly good performances from the kids. Smith was apparently also awfully fond of cats, which recur in his films.

As a technical achievement The Sick Kitten has been praised for its use of multiple cuts & camera angles to convey a single scene that other filmmakers of the time would've restricted to a single stationary camera.

Starring G. A. Smith's wife Laura Bayley, Mary Jane's Mishapp; or, Don't Fool with the Paraffin (1903) is about a slatternly housemaid. Among her morning tasks, she is to light the kitchen stove & polish her master's shoes.

Starring G. A. Smith's wife Laura Bayley, Mary Jane's Mishapp; or, Don't Fool with the Paraffin (1903) is about a slatternly housemaid. Among her morning tasks, she is to light the kitchen stove & polish her master's shoes.

As she polishes the shoes, she manages to get bootblack all over her mouth & nose. Realizing her blunder, she gets a tarnished mirror to check out the stain on her face, which amuses her, as she seems just a mite retarded.

Returning to the stove, her first attempt at a fire seems merely to have gone out. So she poors some liquid parifin into the stove, quite a lot of it in fact, grinning hugely feeling brilliant.

She thereby blows herself up. The camera cuts from the kitchen to the roof, & we see the scullery maid's body shooting out of the chimney as from a cannon, vanishing into the sky, tumbling back into the camera's view a moment later, apparently in three pieces.

There is a "screen wipe," the first ever used in cinema, to take us from the rooftop to a tombstone which reads, "Here Lies Mary Jane, Who Lighted the Fire with Paraffin. Rest In Peaces." There is a "screen wipe," the first ever used in cinema, to take us from the rooftop to a tombstone which reads, "Here Lies Mary Jane, Who Lighted the Fire with Paraffin. Rest In Peaces."

A second screen-wipe shows a more distant shot, of visitors to Mary Jane's grave. They are unexpectedly witnesses to her ghost rising out of her grave!

It almost looks like the visitors brought her to life, except that they are all scared away & evidently as surprised as anyone.

This shocking denoument seems to come from left field, but plays off a very old idea in folklore, that it is possible to be so mentally deficient or incompetent that now & then someone can't even manage to stay dead; having done nothing properly in life, they can't even die right.

Her transparent spirit conjures for itself a jug of liquid paraffin, & with it returns to the grave. Perhaps she intends to help out with the fires of hell or is otherwise up to her old tricks even in the afterlife.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

He looks at the insides of a pocket watch, then he turns to the canary in a hanging cage & looks at it through the lens, again shown through the circular cut-out.

He looks at the insides of a pocket watch, then he turns to the canary in a hanging cage & looks at it through the lens, again shown through the circular cut-out.

There is a "screen wipe," the first ever used in cinema, to take us from the rooftop to a tombstone which reads, "Here Lies Mary Jane, Who Lighted the Fire with Paraffin. Rest In Peaces."

There is a "screen wipe," the first ever used in cinema, to take us from the rooftop to a tombstone which reads, "Here Lies Mary Jane, Who Lighted the Fire with Paraffin. Rest In Peaces."