Some Experimental Piffles of the Silent Era

Le Retour a la Raison (Return to Reason, 1923) is a three-minute dada film made by exposing film directly to small objects, such as nails, mixed with actual photographs, including gosh oh gee a nude. Le Retour a la Raison (Return to Reason, 1923) is a three-minute dada film made by exposing film directly to small objects, such as nails, mixed with actual photographs, including gosh oh gee a nude.

The George Antill music accompanying the modernly distributed version was written two years after the film's debut, but may well be similar to what Antill performed at the actual 1923 debut of Man Ray's film.

In the larger context of Man Ray's photographic work this piffle of a film gains in appeal. If considered as just something on the order of a collection of potato prints in motion, they aren't much to write home about, but the Man Ray nude (of Kiki of Montparnasse) is excellent.

It also gains in interest if one is intrigued by the history of surrealists & dadaists, & knows that a fight broke out in the audience on the night of this film's premiere, between a chap who disliked it & a chap who wanted the chap who disliked it to shut the hell up. Oh what a sandbox those dadaists made for themselves to play in!

The father of Dada, Marcel Duchamp (as "Rrose Selavy"), assisted by Man Ray, gifts us with his seven minute piffle, words on a screen & whirligig spirals. The father of Dada, Marcel Duchamp (as "Rrose Selavy"), assisted by Man Ray, gifts us with his seven minute piffle, words on a screen & whirligig spirals.

The simplicity of the execution has a hypnotic quality as well as some visual punning. The very title of the film, Anemic Cinema (1926), is a pun which the film will clarify.

Anemic Cinema is kind of a companion-film for Duchamp's glass "rotative plaques" from the 1920s, & the sculptured Rotoreliefs that followed. These latter were painted or sculpted or otherwise decorated discs intended to be viewed on the turntables of gramaphones.

These other works are vastly more appealing than the film. Though it is better than most purely dadaist films, it's still largely a minor jest, & of interest mainly for the fact that it's by Duchamp as opposed to Doodly Nobody, Jr.

A fifteen-minute expressionist film somewhat in the manner of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), The Love of Zero (1928) tells the tale of Zero (pantomime artist Joseph Marievski) who falls in love with Beatrix (Tamar Shavrova).

A fifteen-minute expressionist film somewhat in the manner of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), The Love of Zero (1928) tells the tale of Zero (pantomime artist Joseph Marievski) who falls in love with Beatrix (Tamar Shavrova).

They live a blissful life upon a stage of abstract furniture & trapezoid windows & doors, with Zero periodically serenading Beatrix with a trombone while perched on his highchair.

Gloomily parted by fate when Beatrix is recalled to the castle, Zero falls into a forlorn pose. Gloomily parted by fate when Beatrix is recalled to the castle, Zero falls into a forlorn pose.

After long loneliness he finally falls for another woman (Anielka Elter), but she mistreats him with laughter & disdain, leaving him for two other men.

News arrives of the death of Beatrix. Thus there is no chance of Zero ever recovering his lost happiness. The world has become dark, ugly, irksome. Demons surround him, & he is finally destroyed, like a doll snatched away from a toy stage by the hand of a child.

This little film was famously made for only $200, pretty cheap even for 1928. The filmmakers got plenty for their money, too, as this is visually a masterwork, thanks in the main to the gorgeous set design by William Cameron Menzies.

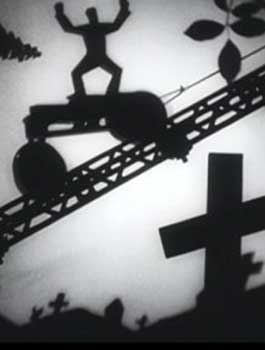

Miniature expressionist sets are the real star of Life & Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra (1927), & render this partially a work of animation. It's on the National Registry as a work of cultural significance. Miniature expressionist sets are the real star of Life & Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra (1927), & render this partially a work of animation. It's on the National Registry as a work of cultural significance.

The thirteen-minute story symbolically criticized the maltreatment of Hollywood extras.

Our naive hero, John Jones (Jules Raucourt), arrives in Art Deco Hollywood all smiles & dreams.

He has a letter of introduction that gets him hired by a casting agent (Robert Florey being quite antic in the film he wrote & co-directed).

As an extra he's known thereafter as 9413, the number being printed right on his forehead. Now begins the endless wait for his number to come up. As an extra he's known thereafter as 9413, the number being printed right on his forehead. Now begins the endless wait for his number to come up.

Other numbers become automatons with fading dreams, but 9413 struggles to remain an individual.

Earning no money, falling deeper in debt for his rent, he is slowly starving to death, while imagining he is surrounded by scorpions.

At last he dies, but continues dreaming even in his coffin. He dreams he is ascending to heaven, or perhaps he really is ascending in the form of a heroic paper cut-out silhouette. In the firmament he becomes a shining star, with wings.

Reportedly filmed for $97.00, one reason it looks so cool is thanks to cinematographer Gregg Toland, who went on to such amazing camera work on films like Citizen Kane.

Slavko Vorkapich made a three-minute extension to Life & Death of 9413, A Hollywood Extra, entitled Legacy of a Hollywood Extra (1928). Without the added talents of Robert Florey on board, however, Vorkapich didn't entirely live up to the original. Slavko Vorkapich made a three-minute extension to Life & Death of 9413, A Hollywood Extra, entitled Legacy of a Hollywood Extra (1928). Without the added talents of Robert Florey on board, however, Vorkapich didn't entirely live up to the original.

Dancing silhouettes are seen against the cityscapes as a giant organ grinder grinds up the world. We're shown extreme drunkenness set just before Prohibition. And the film suddenly ends.

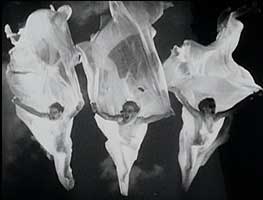

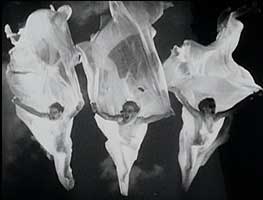

All of the above pieces can be found in the Unseen Cinema early American avant garde dvd film set. There are additional poorly labeled fragments of Vorkapich lifted from longer films, "The Furies" from the opening credits of Ben Hecht & Charles MacArthur's Crime Without Passion (1934); his montages for the Robert Z. Leonard film Maytime (1937); & some test shots for Leonard's The Firefly (1937).

The least meaningless of these is "The Furies" montage. In the main such fragments as these aren't of much interest separate from their films. It is the tacky annoying habit throughout this dvd set to include shitloads of trivial fragments apropos of far too little.

It's as if the compilers were too much in a hurry, or just too stupid, to select from among the many additional fine & complete experimental films that might've made the set eternally worthwhile. As it stands, too much of it is like watching previews or outtakes for films you'd rather see in their entirety if at all.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

Gloomily parted by fate when Beatrix is recalled to the castle, Zero falls into a forlorn pose.

Gloomily parted by fate when Beatrix is recalled to the castle, Zero falls into a forlorn pose.

As an extra he's known thereafter as 9413, the number being printed right on his forehead. Now begins the endless wait for his number to come up.

As an extra he's known thereafter as 9413, the number being printed right on his forehead. Now begins the endless wait for his number to come up.