JAPANESE SWORDSWOMEN V:

GAMBLING NUNS

The martial nun existed in Japanese history, many of whom as a matter of course studied martial arts at women's monasteries, & went on pilgrimmages from shrine to shrine carrying a suzu-zue staff with rings on the top. This was a hardwood pole frequently reinforced with iron.

The martial nun existed in Japanese history, many of whom as a matter of course studied martial arts at women's monasteries, & went on pilgrimmages from shrine to shrine carrying a suzu-zue staff with rings on the top. This was a hardwood pole frequently reinforced with iron.

The rings jangled against one another each time the staff touched the ground, which was believed to scare away demons & evil spirits. And if highwaymen threatened a wandering nun, that same staff became a weapon. If the sect deplored killing, the rings on top of the suzu-zue were large enough to capture & hold a sword

There were numerous sects of "strolling nuns" & even sedate convents required periodic pilgrimmages, so self-defense skills were the minimum requirement. Women of samurai class might become nuns when their husbands died or for other reasons, & some sects let them retain the privilege of carrying swords on their shrine pilgrimmages. There were numerous sects of "strolling nuns" & even sedate convents required periodic pilgrimmages, so self-defense skills were the minimum requirement. Women of samurai class might become nuns when their husbands died or for other reasons, & some sects let them retain the privilege of carrying swords on their shrine pilgrimmages.

Some widows of warriors would join such sects as the Fuke Buddhists who travelled incognito as onna-komuso or woman-mendicant, being most numerous in the 1600s & early 1700s. Because they were "retired" from the world, they wore large basket-like incognito hats called tengai. The sect appealed to ronin who found an acceptable way of becoming beggars in the sect, & by widows of samurai.

Ex-samurai Fuke Buddhists did not retain the right to carry swords, though there are some kabuki portraits of komuso characters that suggest they sometimes did so anyway. More commonly they used a musical instrument for a weapon.

This was the shakuhachi flute which Fuke buddhists modified to be simultaneously a sturdy, dangerous clubbing weapon. One legend presumes that nuns were the first komuso to play the shakuhachi, & wrote the classical compositions as forms of prayer, the original purpose of which was to ease birth pangs by playing their flutes in birthing huts, such nuns having been trained as midwives.

Female komuso might be samurai of either sex, or kunoichi (women ninjas) who didn't want their identities known. Female komuso might be samurai of either sex, or kunoichi (women ninjas) who didn't want their identities known.

It came to be a common assumption that komuso could well be shogunate spies at a time when they were given exclusive privilege to gain alms with the shakuhachi, in exchange for which exclusivity they would report rebellious activities to officials. But other komuso were themselves rebels who used their right of wandering to gather information against the shogunate.

In more decadent generations the komuso could well be itinerate prostitutes of either sex. There's a famous woodblock portrait by Koryusai of a wakashu or boy harlot travelling with a courtesan, & both of them are carrying shakuhachi flute in one hand, komuso incognito-hats in the other, doffed to advertise their beauty.

I've reproduced an image of that print here just because it is so amazing. With additonal reference to the sexual decadence of Tomisaburo Wakayama's Wicked Priest series in which being a Buddhist monk is portrayed as just the thing for a horndog on the make, it would appear there was more than cinematic fantasy to that notion.

There are two other onna-komuso portraits shown above left, one an early primitive block print, the other a late decadent example, these two images framing the entire Tokugawa period.

Women komuso & other sorts of martial nuns became recurring figures of kabuki theater. It is just such theatrical & historical realities that seeped into Japanese cinema, & martial nuns pop up as side characters in sundry films, such as Tatsuya Wakayama's "Karate Killer Priest" or "Wicked Priest" series that has an woman assassin in one episode, a martial nun in another.

Some of the negative connotations of nuns arose from anti-religious literature & sentiment, or from erotic fantasy, but history assures us none of it was invented from whole cloth. The association of nuns with decadence, prostitution, &/or warrior prowess led to a recurring character of gambling nuns in yakuza or gangster films, usually Buddhist, sometimes Christian.

Some of the negative connotations of nuns arose from anti-religious literature & sentiment, or from erotic fantasy, but history assures us none of it was invented from whole cloth. The association of nuns with decadence, prostitution, &/or warrior prowess led to a recurring character of gambling nuns in yakuza or gangster films, usually Buddhist, sometimes Christian.

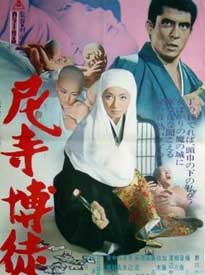

Yumiko Nogawa stars as Haraku in The Gambling Nun (Amadera bakuto, Toei, 1971). In the film's opening tanto knife-fighting scene, Haraku's father kills three punks & injures several others because they had falsely accused his daughter, who'd been working in a gambling house as a woman dicer, of cheating them in the game.

They were not good fellows by any means, but it's later admitted that one had a child & another a girl who cared for him a great deal. Haraku's father is sent to prison & Haraku herself enters a Buddhist convent to help her father pay his spiritual debt. She has sworn to remain a nun until her father, too, is released from confinement.

One-third yakuza-eiga & two-thirds nun-sexploitation flick, of course this is going to be a pretty damned misogynist length of celluloid, & anyone who hopes for a variant of the wonderful Red Peony Gambler series is apt to be disappointed. It nevertheless has some serious, moody, heroic moments. One-third yakuza-eiga & two-thirds nun-sexploitation flick, of course this is going to be a pretty damned misogynist length of celluloid, & anyone who hopes for a variant of the wonderful Red Peony Gambler series is apt to be disappointed. It nevertheless has some serious, moody, heroic moments.

Virgin nuns are "sold" to rich old men in exchange for their patronage to the convent. Convent repair funds are embezzled by a nun's male lover. The main "pinku" pornographic sequence has two bald-headed nuns going at it, filmed in a style contradicting the pictorial cinematography of the rest of the film, close-ups of bodies clinging & tongues licking, & a sadomasochistic context.

After the lesbian sequence, a voyeuristic nun flees to the convent gardens & seems about to throw up in disgust. Found by Haraku, the novice tells what she has seen, & Haraku becomes the epitome of the libertine in counselling the novice: "This is a woman's castle. Things happen." A nice line in a weak film.

A sordid plan is in the making, to sell the centuries-old convent & surrounding lands because of high real estate value, & move the nuns to a suburban property. This greedy intent originated within the convent itself, but is soon taken over by merciless gangsters, at which point Haraku, with her knowledge of yakuza mores & manners, seems likely to be able to help.

The nunsploitation element assumes most of these women are depraved & greedy, but it is interesting that the ultimate villains are the yakuza, not the corrupt nuns. We even end up pitying the most corrupt of all the nuns, whose lover commits suicide to atone for his embezzling & gambling debt which brought the yakuza into the picture. The nunsploitation element assumes most of these women are depraved & greedy, but it is interesting that the ultimate villains are the yakuza, not the corrupt nuns. We even end up pitying the most corrupt of all the nuns, whose lover commits suicide to atone for his embezzling & gambling debt which brought the yakuza into the picture.

Haraku is a superhero throughout, in terms of her idealism. As a nun, she is not allowed to gamble, even if by doing so she might win back the convent's lands. Yet she cannot cease to be a nun until her father is free from prison, as she cannot break from her own devout oath.

As luck would have it, her father is about to drop dead. He has been ill from an internal injury received from one of the punks he killed. His death scene is less moving than it could have been, since it is timed so very conveniently to allow Haraku to return to the gambling world in the nick of time.

Her father's death scene is all the more contrived when his final words are a warning about how she will be cheated in a forthcoming game. He has absolutely no way of knowing the method by which the gangsters plan to cheat, except that he dreamed it on his deathbed. So he warns her to watch the veins of the dealer's hands to know when he attempts to alter a card. Her father's death scene is all the more contrived when his final words are a warning about how she will be cheated in a forthcoming game. He has absolutely no way of knowing the method by which the gangsters plan to cheat, except that he dreamed it on his deathbed. So he warns her to watch the veins of the dealer's hands to know when he attempts to alter a card.

In many a film with similar theme, a dying friend or father gives just such a warning, but it is always because they have overheard or otherwise learned by some rational means that something rotten has been planned, & often the person is at death's door due to an attempt to silence him of his knowledge. In The Gambling Nun it seemed as though the screenplay had been written into a corner; when it was time to provide a dying man's last words of warning, the father was never previously shown to be in any position to have essential information about anything. So the scriptwriter just decided to have him dream it then die.

And yes indeedy, the dream is correct. In the final gambling scene, with the deed to the convent in the offering, the dealer cannot switch the card because Haraku is staring so intentsely at the man's veins. When she wins the game, the bad guys decide to kill her. She draws her tanto & defends herself admirably, cutting the fellows up while she tears the legal papers into pieces, ruining their plan even if they kill her.

Haraku's boyfriend has been a minor character in the film, a decent chap promising to wait until she is no longer a nun so they can wed. This minor figure pops up in the final fight in order to kill the villain, though the storyline might have been better served by letting Haraku perform this action herself. Haraku's boyfriend has been a minor character in the film, a decent chap promising to wait until she is no longer a nun so they can wed. This minor figure pops up in the final fight in order to kill the villain, though the storyline might have been better served by letting Haraku perform this action herself.

She fights well, but the fundamentally misogynist script could not let her provide the story's climactic slaying. A small loss, perhaps, since the bulk of the film was too weak to merit a satisfying conclusion.

As Haraku wasn't a powerful enough hero to win her own battle in the end, neither were the corrupt nuns so villainous as to be the chief causes of trouble in their convent. Whether good bad, women are ultimately weak things compared to men. For a story dominated by images of women, men manage to be both the strongest heroic type & the villainous types.

In all, this film is a terrific example of male fantasies of women & convent life, but it falls far short of being the kind of great lady-yakuza film such as are embodied by the Red Peony Gambler.

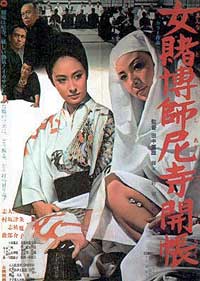

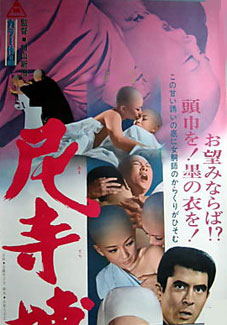

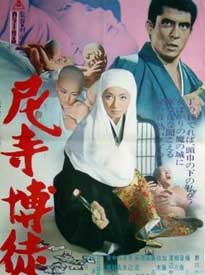

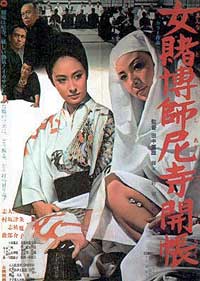

Gambling nuns recur in these sorts of films, & a much better example can be seen in Shigeo Tanaka's Woman Gambler & the Nun (Daiei, 1968) & its immediate sequel The Woman Gambler's Supplication (Daiei, 1968). And the poster shown a little above on this page is for Kazuo Ikehiro's The Daring Nun (Ama kuzure, Daiei, 1968) with Michiyo Ookusu (aka Michiyo Yasuda) as the bold Sister Shunko. Martial nuns are also frequently encountered in ninja movies though of course they're usually kunoichi (female ninja) disguised as nuns.

All in all, the martial Buddhist nun who appears in the Karate Killer Priest series & teaches Wakayama he can fight even though temporarily blind, is entirely plausible. All in all, the martial Buddhist nun who appears in the Karate Killer Priest series & teaches Wakayama he can fight even though temporarily blind, is entirely plausible.

Christian nuns are less commonly encountered in action cinema, though with the rise of pinku in the 1970s there were sexploitation films for nun fetishists, the best of which being School of the Holy Beast (Sei-ji gakuen, 1974).

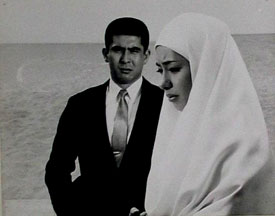

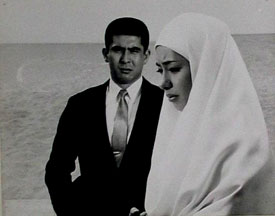

An exception was The Second is a Christian (Nidaime wa Christian, 1985) based on a novel by Tsuka Kouhei. It mixes comedy with convent-yakuza thrills. An exception was The Second is a Christian (Nidaime wa Christian, 1985) based on a novel by Tsuka Kouhei. It mixes comedy with convent-yakuza thrills.

Like yakuza-eiga of the 1960s, the bulk of the film has no action, then the last reel is all-out-action.

The larger part of the tale is about a nun deciding who she'd rather have as her lover, the honest cop Detective Kumashi (Akira Emoto) or the handsome gangster Haruhiko Tenryu (Koichi Iwaki).

Haruhiko has become an oyabun (godfather) of a small gang after his father's death. He & his lads are being harrassed by the bad oyabun of a larger gang.

Haruhiko is in love with the pretty nun Kyoko & she loves him. But eventually killed by his previous girlfriend, Yuri (Rino Katase).

However, waiting for the hot nun sex scene will disappoint nunsploitation fans since Etsuko Shiomi just wasn't the pinku kind of actress. She had a large teenage following, being one of the two most famous performers to come out of Sonny Chiba's Japan Action Club. However, waiting for the hot nun sex scene will disappoint nunsploitation fans since Etsuko Shiomi just wasn't the pinku kind of actress. She had a large teenage following, being one of the two most famous performers to come out of Sonny Chiba's Japan Action Club.

The Second is a Christian was made near the end of Etsuko's action-film career. The role is more like a Red Peony Gambler chivalrous lady yakuza, but rendered a bit absurd by a nun's habit. She tries & tries to adhere to Christian forgiveness instead of the road to vengeance.

But as the bad yakuza boss Kuroiwa gets more & more malicious, Kyoko has to take up sword for the final confrontation with all the baddies in their headquarters. Alas, she doesn't do it in her nun's habbit, which would've cinched this as a hoot.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

There were numerous sects of "strolling nuns" & even sedate convents required periodic pilgrimmages, so self-defense skills were the minimum requirement. Women of samurai class might become nuns when their husbands died or for other reasons, & some sects let them retain the privilege of carrying swords on their shrine pilgrimmages.

There were numerous sects of "strolling nuns" & even sedate convents required periodic pilgrimmages, so self-defense skills were the minimum requirement. Women of samurai class might become nuns when their husbands died or for other reasons, & some sects let them retain the privilege of carrying swords on their shrine pilgrimmages. Female komuso might be samurai of either sex, or kunoichi (women ninjas) who didn't want their identities known.

Female komuso might be samurai of either sex, or kunoichi (women ninjas) who didn't want their identities known.

One-third yakuza-eiga & two-thirds nun-sexploitation flick, of course this is going to be a pretty damned misogynist length of celluloid, & anyone who hopes for a variant of the wonderful

One-third yakuza-eiga & two-thirds nun-sexploitation flick, of course this is going to be a pretty damned misogynist length of celluloid, & anyone who hopes for a variant of the wonderful

Her father's death scene is all the more contrived when his final words are a warning about how she will be cheated in a forthcoming game. He has absolutely no way of knowing the method by which the gangsters plan to cheat, except that he dreamed it on his deathbed. So he warns her to watch the veins of the dealer's hands to know when he attempts to alter a card.

Her father's death scene is all the more contrived when his final words are a warning about how she will be cheated in a forthcoming game. He has absolutely no way of knowing the method by which the gangsters plan to cheat, except that he dreamed it on his deathbed. So he warns her to watch the veins of the dealer's hands to know when he attempts to alter a card.

An exception was The Second is a Christian (Nidaime wa Christian, 1985) based on a novel by Tsuka Kouhei. It mixes comedy with convent-yakuza thrills.

An exception was The Second is a Christian (Nidaime wa Christian, 1985) based on a novel by Tsuka Kouhei. It mixes comedy with convent-yakuza thrills. However, waiting for the hot nun sex scene will disappoint nunsploitation fans since Etsuko Shiomi just wasn't the pinku kind of actress. She had a large teenage following, being one of the two most famous performers to come out of Sonny Chiba's Japan Action Club.

However, waiting for the hot nun sex scene will disappoint nunsploitation fans since Etsuko Shiomi just wasn't the pinku kind of actress. She had a large teenage following, being one of the two most famous performers to come out of Sonny Chiba's Japan Action Club.