Subliminal & Overt Homosexual Eroticism in Chivalrous Yakuza-eiga

The standard themes of classical yakuza-eiga (Japanese gangster films) demand friendships between men & devotion to a patriarchal oyabun (godfather), lending an essential homosocial & sometimes homoerotic sense to these films. The standard themes of classical yakuza-eiga (Japanese gangster films) demand friendships between men & devotion to a patriarchal oyabun (godfather), lending an essential homosocial & sometimes homoerotic sense to these films.

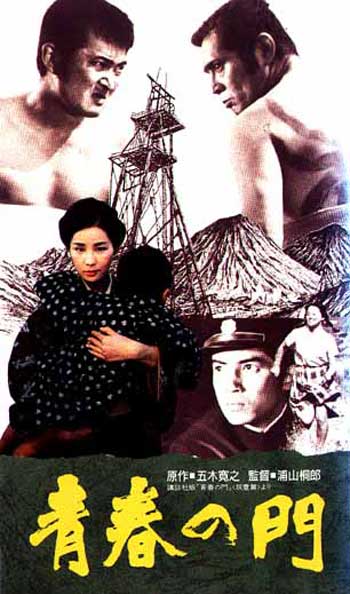

In Gate of Youth (Seishun no Mon, Toho, 1975; first & second illustrations are for this film) the hero Shinsuke (Ken Tanaka) explicitly falls in love with an oyabun Goro (Akira Kobayashi).

Riding on the back of the handsome gang leader's motorcycle, with the side of his face pressed against the older man's leather-clad back, the young hero is both frightened & exillerated & does not want to let go when the motorcycle stops. In another scene, with a punk yakuza his own age, our hero allows himself to actually be masturbated.

It's rare that so much background is provided for a yakuza character, but we see Shinsuke's life from childhood on, in an epic-length film. Shinsuke's farther Juzu "Spider Tattoo" Ibuki (Tatsuya Nakadai) is killed while heroically trying to save Korean coal miners, & Shinsuke is thereafter something of a momma's boy with only his stepmother (Keiko Sekine). Shinsuke's outsider status stems from his being an orphan, associating with Koreans & gangsters, & his sexual ambiguity.

Historically & traditionally, homoeroticism has lacked, in Japan, the same high degree of stigma it has had in the west, though gay relationships are not supposed to interfer with other dutiful activities like eventually getting married & raising a family. Samurai society was to large extent a homosexual or bisexual society like that of the Dorians or Spartans. So latterday yakuza, aspiring to samurai-like behavior patterns, are apt to emulate that.

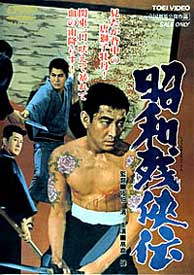

In 1960s yakuza-eiga this is a subtle subtext in more films than not. In 1970s films this aspect of yakuza life was increasingly apt to be treated disparagingly, as in the seventh episode of the New Abashiri Prison series The Great Escape (Shin Abashiri Bangaichi: Fubuki no Dai-dasso, Toei, 1971; its poster is here at the left) in which the villain & his drag-queen lover are treated grotesquely, much as might be expected in an American film. In 1960s yakuza-eiga this is a subtle subtext in more films than not. In 1970s films this aspect of yakuza life was increasingly apt to be treated disparagingly, as in the seventh episode of the New Abashiri Prison series The Great Escape (Shin Abashiri Bangaichi: Fubuki no Dai-dasso, Toei, 1971; its poster is here at the left) in which the villain & his drag-queen lover are treated grotesquely, much as might be expected in an American film.

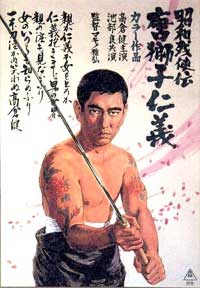

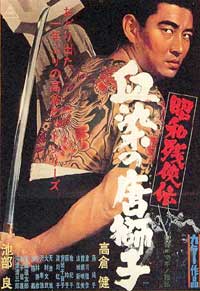

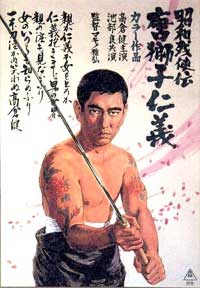

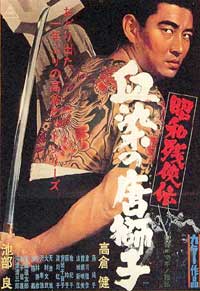

As a generality, interesting & positive treatments of homoeroticism is to be expected, rarely so overt that anyone uncomfortable with it needs to notice. In The Man with the Dragon Tattoo (Showa Zankyo-den: Karajishi jingki, Toei, 1968; its poster is here at right), Ken Takura & Ryo Ikebe start out as enemies & end up walking together into danger, cherry blossoms overhead, sharing the same umbrella.

This image of the shared umbrella has symbolized lovers in the Japanese arts since time immemorial, & much as in the west lovers put their names inside a heart, in Japan carving a simple image of an umbrella with the names of the lovers flanking the handle has the same importance. This image of the shared umbrella has symbolized lovers in the Japanese arts since time immemorial, & much as in the west lovers put their names inside a heart, in Japan carving a simple image of an umbrella with the names of the lovers flanking the handle has the same importance.

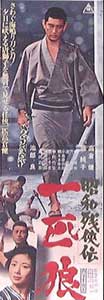

The relationship is similar in Kiyoshi Saeki's Shige, Lone Wolf (Showa Zankyo-den: Ippiki okami, Toei, 1966; poster & still shown near these paragraphs), which even repeates the "shared umbrella" symbolism, while making men's love even gloomier & more sincere. The superficial romantic couple are played by Ken Takakura & Junko Fuji, yet that is not not nearly as emotionally played as the love between Ken's character & that of Ryo Ikebe.

Set early in the Showa Era (in the late 1920s & early 1930s), Ryo Ikebe's character suddenly tells Ken Takakura, "Maybe you attracted me. No, only my sister," & gives up their duel. Set early in the Showa Era (in the late 1920s & early 1930s), Ryo Ikebe's character suddenly tells Ken Takakura, "Maybe you attracted me. No, only my sister," & gives up their duel.

Then on Ken's march to the final raid, his "foe" Ikebe joins him, respectfully, walking behind him like a wife. Even Ken's full body tattoo of shishi lion & flowers reflects his tough-bodied & the softhearted nature. This is a film of superior pathos & longswords, ending in the double tragedy of Ken's imprisonment & ikebe's death.

Homosexuality as a theme or practice has been integral to theatrical arts from at least the early Tokugawa period, with the advent of Wakashu-kabuki ("beautiful young man theater") with plays specifically about samurai & their pretty pages. The first regulations of the Tokugawa government forcing wakashu to shave their forelocks was a hopeless attempt to use the law to make young men less appealing to horny samurai, as such liasons were supposed to lead to mentorships between younger & older samurai, not to lusty relationships with actors or boy harlots (for a bit more on this topic, see the article which discusses gender-bent performances in such films as Benten Kozo).

The sort of explicit homoeroticism seen in history, or in Takashi Miike's latterday yakuza films Gozu (2003) & Ichi the Killer, (2001) is rarely so extreme in the classic yakuza-eiga. Rather, homosexuality is only a subtext which Miike fishes out into full view.

The subliminality of the earlier films permits it to go unseen by anyone who prefers not to notice. In an interview by Joan Mellon with Sachiko Hidari, the actress observed the commercial value of this subtext, noting, "Younger people now like the type of men with an air of homosexuality." The subliminality of the earlier films permits it to go unseen by anyone who prefers not to notice. In an interview by Joan Mellon with Sachiko Hidari, the actress observed the commercial value of this subtext, noting, "Younger people now like the type of men with an air of homosexuality."

When she asserted this, director Susumi Hani interupted to say, "I don't think so." Hidari insisted, "Yes, it's true." That she saw it & he did not see it was a perfect example of how easily an important element of the genre can be ignored. But even for viewers who are naive to this ingredient, it inevitably seeps into their subconscious.

In the heyday of the chivalrous gambler films, women & girls loved the films as much as did men & boys, for sad-eyed beautiful men of valor & sensitivity toward their boyfriends have a definite girl appeal as well as youth appeal. In the post-classical yakuza films which became increasingly brutal, homosexuality became more an element of overall crazed deviance rather than evidence of sensitivity, & women were no longer so great a percentage of the audience.

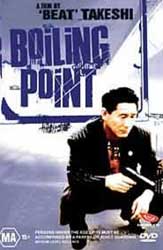

In Takeshi Kitano's Boiling Point (Juugatsu, Shochiko Fuji, 1990) for further example, attempts at homosexual seduction in the Okinawa gang world is just one more aspect of the unwholesomeness of that world.

Or in Rokuro Mochizuki's The Fire Within (Onibi, 1997) in which the macho hero Kunihiro has an obvioius husband/wife relationship with an effeminate criminal. In the classical period they would've been equals, both men sensitive yet manly, not merely imitation heterosexuals with an exaggerated butch & femme dichotomy. Or in Rokuro Mochizuki's The Fire Within (Onibi, 1997) in which the macho hero Kunihiro has an obvioius husband/wife relationship with an effeminate criminal. In the classical period they would've been equals, both men sensitive yet manly, not merely imitation heterosexuals with an exaggerated butch & femme dichotomy.

Or, the queer hitman in Shark-skin Man & Peach-hip Girl (Samehada otoko to momojiri onna, 1998) is played for camp value.

It appears as though the respect accorded homoerotic relationships in classical yakuza-eiga was only possible because it was mere subtext without actual sex acts. When it becomes conscious & overt, the directors & writers can't resist camping it up or using homosexuality only as one more element of the badness of criminals' lives. It appears as though the respect accorded homoerotic relationships in classical yakuza-eiga was only possible because it was mere subtext without actual sex acts. When it becomes conscious & overt, the directors & writers can't resist camping it up or using homosexuality only as one more element of the badness of criminals' lives.

The romance of it was only sustainable as a sexual tension always on the verge of declaring itself but never doing so. And it was always preferrable if the heterosexual male viewer could relate only to the manly part of these classical characters, or that the female viewer could imagine herself as the sensitive hero's heart-throb. It is only the possibility & not the certainty of homosexuality that is sexy in these characters, & when it becomes a certainty in the gangster films of the 1990s & after, it becomes decreasingly respected.

Although this element is subliminal to classical yakuza-eiga, once one becomes aware of it, it seems increasingly overt. Many standard bits of dialogue, as when Ken Takakura says to someone like Ryo Ikebe or Koji Tsuruta, "Men's love is great," the thrill that runs through the audience is not at all an asexual ripple.

The realistic origin of this subtext is at least in part due to the fact that many young gangsters of the actual yakuza organizations were indeed bisexual or gay, accounting for the alienation or differentness that put them in the "shadow world" or closet of the criminal underworld to begin with.

In films of the mid-60s until the early '70s, heterosexual love is rarely a character motivation, but men's love often is. Only if the woman was herself yakuza & the central protagonist, as in the Red Peony Gambler series (Hibotan Bakuto, 1968-72), did she become the motivator of men. And in that exceptional case she was also the leader of men fighting as an equal. So even in this case the relationship between Red Peony & the male lead emulate male bonding. I.e., the Romeo-&-Juliet tragedies of the Red Peony series are strikingly similar to the Romeo-&-Romeo tragedies of so many other yakuza films.

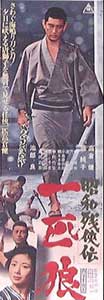

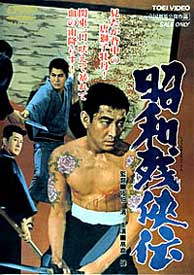

The more common yakuza-eiga treats relationships with women as superfluous. If anything, interest in a woman works against the male hero's necessary action. She fears losing him & tries vainly to talk him out of it, as in Symbol of Courage aka Dragon Tattoo: Full of Blood (Showa Zankyo-den: Chizome no Karajishi, Toei, 1967; poster here at right) in which Fuji Junko plays a whining, pleading girlfriend, the opposite of her Red Peony charcterization. (The Showa Zankyo-den series has been called both the "Dragon Tattooed Man" series though it's a Chinese lion tattoo, & more accurately the "Contemporary Tales of Chivalry" or "History of the Remaining Chivalry in the New Era," 1965-1971.) The more common yakuza-eiga treats relationships with women as superfluous. If anything, interest in a woman works against the male hero's necessary action. She fears losing him & tries vainly to talk him out of it, as in Symbol of Courage aka Dragon Tattoo: Full of Blood (Showa Zankyo-den: Chizome no Karajishi, Toei, 1967; poster here at right) in which Fuji Junko plays a whining, pleading girlfriend, the opposite of her Red Peony charcterization. (The Showa Zankyo-den series has been called both the "Dragon Tattooed Man" series though it's a Chinese lion tattoo, & more accurately the "Contemporary Tales of Chivalry" or "History of the Remaining Chivalry in the New Era," 1965-1971.)

Symbol of Courage is another typical example of the genre's sublimated homoeroticism. Ken Takakura stars as a man recently home from Manchuria. He has inherited the management of a construction company & is boss over numerous workers whose livelihoods are threatened by yakuza, who want to muscle in on the contracts & take over the business. Takakura will untilmately be forced to revert to the wildness of his life before the war, revealing his dragon body tattoo, heralding the climactic battle.

His co-star, Masahiko Tsugaura, is an idealistic yakuza living by the code of fair play & devotion to the oyabun. In this case, as often happens for the rare idealistic yakuza, the two ideals don't go well together, for the oyabun is an evil boss trying to take over the construction company from honest workers. To betray the boss breaks the code of duty. But to obey him goes aginst humanity or fair play. He gets around the dilemma without much effort, for his short-sighted boss casts him out of the group, having heard enough of his humanity tommyrot. Now it is possible to join his life-long friend in the final raid.

The sensual friendship of hero & hero's friend is not expected to be consumated by sexual acts, of course, but by the climactic battle which becomes a metaphor for orgasm. Side by side, they enter the headquarters of the evil boss's gang, for a protracted sword battle which is the climax of the film's hour-plus of foreplay.

In Symbol of Courage the best friend dies, & the hero survives to be taken off to prison (& to await the next sequel in the Dragon or Lion-Tattooed Man series). Sometimes both men survive, however, & sometimes both are dead by the end. Occasionally, the best friend is murdered before the final confrontation, which the hero fights alone, in revenge. Within the conventions of chivalrous gambler cinema, just such slight variations form tapestries which despite being very similar one film to the next nevertheless express subtle distinctions that become important to the genre's afficianados.

The female lead's only act of courage in Symbol of Courage was the dramatic act of sewing the kimono which the hero will wear on the raid, accompanied by his truer love & equal, a man.

The full color widescreen Contemporary Tales of Chivalry series is at the high end of ninkyo chivalrous gangster films. It was the first film in the series that shot Ken Takakura to superstardom & defined his basic heroic character-type up to about 1972 when the ninko style of yakuza-eiga finally fell from fashion & Ken made a transition into more or less straight dramatic roles (while other ninkyo stars either became unemployed or adapted to the new style of yakuza film devoid of chivalry). The full color widescreen Contemporary Tales of Chivalry series is at the high end of ninkyo chivalrous gangster films. It was the first film in the series that shot Ken Takakura to superstardom & defined his basic heroic character-type up to about 1972 when the ninko style of yakuza-eiga finally fell from fashion & Ken made a transition into more or less straight dramatic roles (while other ninkyo stars either became unemployed or adapted to the new style of yakuza film devoid of chivalry).

In the Kiyoshi Saeki-directed premier episode Black Market Game (Showa Zankyo-den, 1965; its poster is on the left near this paragraph), it is the aftermath of the Pacific War & Japan is under American occupation. Shinji's old neighborhood lies in ruins. He oversees an open-air market & promised the previous market boss that he would keep the market honest.

As it becomes increasingly difficult to keep the black marketeers at bay, violent incursions become too much to bare. Shinji (Ken Takakura) & his doting doe-eyed buddy (Ryo Ikebe) set out on the final march toward the gangster headquarters, Ikebe with gun, Ken with longsword. During the justice-seeking carnage, Ikebe will die; Ken will survive to be hauled off to jail. As it becomes increasingly difficult to keep the black marketeers at bay, violent incursions become too much to bare. Shinji (Ken Takakura) & his doting doe-eyed buddy (Ryo Ikebe) set out on the final march toward the gangster headquarters, Ikebe with gun, Ken with longsword. During the justice-seeking carnage, Ikebe will die; Ken will survive to be hauled off to jail.

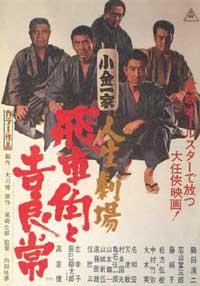

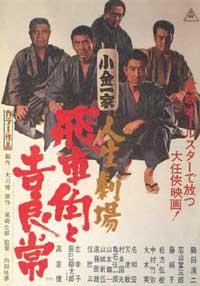

An interesting exception to this sort of yakuza-eiga homoeroticism is Kaku & Tsune (Jinsei gekido: Hishakaku to kiratsune, Toei, 1968; poster here at right) directed by Tomu Uchida, who also did the six-part Musashi the Warrior series starring Kinnosuke Nakamura. Even Kaku & Tsune has sexual tension between the two male stars, but it does not undercut the female love-interest.

Koji Tsuruta, who in real life trained to be a Kamikaze pilot, but the war ended immediately before his mission, plays the gambler Kaku. Junko Fuji is the woman for whom he kills, only to have her fall for another man (Ken Takakura). She is a moralistic character, guilt-ridden to be unfaithful even if only in her mind, tortured by her feelings for the other man & by their inability to injure Kaku by consumating their love. But as in the more homoerotic films, sacrifices made by heros for women go unrewarded by all parties, as the only possible consumation of love is the back-to-back battle of equals against all inhumanity.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

This image of the shared umbrella has symbolized lovers in the Japanese arts since time immemorial, & much as in the west lovers put their names inside a heart, in Japan carving a simple image of an umbrella with the names of the lovers flanking the handle has the same importance.

This image of the shared umbrella has symbolized lovers in the Japanese arts since time immemorial, & much as in the west lovers put their names inside a heart, in Japan carving a simple image of an umbrella with the names of the lovers flanking the handle has the same importance. Set early in the Showa Era (in the late 1920s & early 1930s), Ryo Ikebe's character suddenly tells Ken Takakura, "Maybe you attracted me. No, only my sister," & gives up their duel.

Set early in the Showa Era (in the late 1920s & early 1930s), Ryo Ikebe's character suddenly tells Ken Takakura, "Maybe you attracted me. No, only my sister," & gives up their duel. The subliminality of the earlier films permits it to go unseen by anyone who prefers not to notice. In an interview by Joan Mellon with Sachiko Hidari, the actress observed the commercial value of this subtext, noting, "Younger people now like the type of men with an air of homosexuality."

The subliminality of the earlier films permits it to go unseen by anyone who prefers not to notice. In an interview by Joan Mellon with Sachiko Hidari, the actress observed the commercial value of this subtext, noting, "Younger people now like the type of men with an air of homosexuality." Or in Rokuro Mochizuki's The Fire Within (Onibi, 1997) in which the macho hero Kunihiro has an obvioius husband/wife relationship with an effeminate criminal. In the classical period they would've been equals, both men sensitive yet manly, not merely imitation heterosexuals with an exaggerated butch & femme dichotomy.

Or in Rokuro Mochizuki's The Fire Within (Onibi, 1997) in which the macho hero Kunihiro has an obvioius husband/wife relationship with an effeminate criminal. In the classical period they would've been equals, both men sensitive yet manly, not merely imitation heterosexuals with an exaggerated butch & femme dichotomy.  It appears as though the respect accorded homoerotic relationships in classical yakuza-eiga was only possible because it was mere subtext without actual sex acts. When it becomes conscious & overt, the directors & writers can't resist camping it up or using homosexuality only as one more element of the badness of criminals' lives.

It appears as though the respect accorded homoerotic relationships in classical yakuza-eiga was only possible because it was mere subtext without actual sex acts. When it becomes conscious & overt, the directors & writers can't resist camping it up or using homosexuality only as one more element of the badness of criminals' lives.

As it becomes increasingly difficult to keep the black marketeers at bay, violent incursions become too much to bare. Shinji (Ken Takakura) & his doting doe-eyed buddy (Ryo Ikebe) set out on the final march toward the gangster headquarters, Ikebe with gun, Ken with longsword. During the justice-seeking carnage, Ikebe will die; Ken will survive to be hauled off to jail.

As it becomes increasingly difficult to keep the black marketeers at bay, violent incursions become too much to bare. Shinji (Ken Takakura) & his doting doe-eyed buddy (Ryo Ikebe) set out on the final march toward the gangster headquarters, Ikebe with gun, Ken with longsword. During the justice-seeking carnage, Ikebe will die; Ken will survive to be hauled off to jail.