Because the story imbedded in Institute Benjamenta: This Dream People Call Life (1995) is slow & obscure, this will never be a film for everyone. Because the story imbedded in Institute Benjamenta: This Dream People Call Life (1995) is slow & obscure, this will never be a film for everyone.

But whomsoever is already enamored of Robert Walser, Franz Kafka, & Bruno Shulz will want to see everything by the Brothers Quay, including this remarkable film set in the ghostly world of a university of servitude.

It's beautifully designed with silvery black & white cinematography, well-acted by gloomly sods, with an especially good performance from Mark Rylance as Jakob, who looks startlingly like some of the puppets encountered in brothers Quay stop-motion animation.

Jakob is so quiet, he seems all the more like one of those speechless maniquins from The Street of Crocodiles (1986). It is the silence of films by the brothers Quay that gives them such power of imagination, & for Institute Benjamenta they found a balance between that quietude even in the presence of dialogue, something they would in the following decade fail to achieve with their second live-action film.

A matching fine performance is provided by Alice "Borg Queen" Krige as the frightened seductress turned sleeping beauty. She & her sexually suppressed brother (Gottfried John) run the Institute, & Jakob's presence seems to be an unintended catalyst to break down their rigid sense of the meaning & nature of servitude.

If there's a plot, to outline it would sound silly, much as would Eraserhead (1977), but it somehow functions in the manner of a dream, a work of considerable beauty & suggestiveness. If there's a plot, to outline it would sound silly, much as would Eraserhead (1977), but it somehow functions in the manner of a dream, a work of considerable beauty & suggestiveness.

Familiarity with Robert Walser's novel Jakob von Gunten (1908) would help deconstruct a percentage of the surrealism into clearer meaning, though expecting too much of the book to be reflected in the film might lend mroe disappointment than comprehension, & it'll be equally or more interesting as something unfamiliar.

As the first feature film by the brothers Quay whose earlier films are rather short, & their first with live actors instead of puppetry, they manage to presrve the eerie beauty of their puppetry by placing the living characters in a realm very like that of Crocodiles, & make it credible.

Visually it is like looking into the sinkhole of a depressive's soul, so subtly horrific yet mesmerizing that long lingering shots become hypnotic rather than tedious. And here & there are bits of their stop-motion animation, sufficient to please all who fell in love with them long ago & might otherwise be disappointed the puppetry is gone.

The filmmakers would not do nearly so beautifully in their second live-action feature, The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes (2005).

The filmmakers would not do nearly so beautifully in their second live-action feature, The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes (2005).

Dr. Emmanuel Droz (Gottfried John) is obsessed with Malvina van Stille (Amira Casar), a famed opera singer. Droz has been stalking her, with plans to preserve her forever as an automaton "in my cage."

The Piano Tumer of Earthquakes attempts to do with live-action characters what the brothers Quay have done so elegantly with puppetry & stop motion in such tremendous works of art as The Street of Crocodiles. Alas, the human characters make it kind of boring, & the dialogue makes it too often silly.

The Quay brothers remain at their best with the unstringed marionette given seeming independence, but no speech. If the wandering youth in Street of Crocodiles had burst out with a line of dialogue "I have a hole in the top of my head," it would've been less rather than more miraculous, & the speechifying cast of Piano Tuner all too often seem to be telling a story the beautiful sets failed to tell.

When the occasional great moment burst forth in The Piano Tuner, it's inevitably at moments similar to their films without live-action players, as when we glimpse a stop motion figure in the woods chopping down a tree; or the images of the eerie automated music boxes. When the occasional great moment burst forth in The Piano Tuner, it's inevitably at moments similar to their films without live-action players, as when we glimpse a stop motion figure in the woods chopping down a tree; or the images of the eerie automated music boxes.

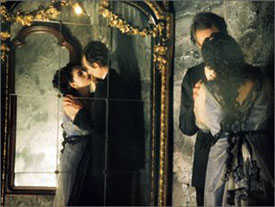

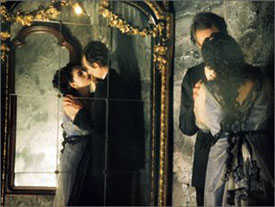

The human players move through a world of dark & shadow, a world which bleeds easily into nightmare, as when Malvina dies mysteriously upon the stage. Her body is taken away to Drost's gothic mansion where his strange science is to be used to reanimate her.

Droz hires the piano tuner (Cesar Saracho) though there are no pianos anywhere in his abode. The piano tuner wonders, as well he might, why he was brought here under false pretenses. He was actually hired to tune seven automata, Drost's elaborate & enormous music boxes which are veritable worlds unto themselves, & which are snares for memory that just might supplant the real world for whoever falls under the influence of the terrible machines.

Special guests have been invited so there is not much time to prepare for the concert. All this sounds a lot more interesting when it's described than it turns out to be when it's seen. It is dragged down by the welter of goofy slowly spoken dialogue, characters standing around telling the story rather than enacting the story, & a cast who one after another turn out to be dull as dirt.

That the characters come off as puppets even though they're not is perhaps intended to be ironic, given the artifice of film entire, & the threat of becoming automata. I can't help but feel there is greater irony in Quay films that assume humanity to puppets, than in a film that moves its actors in such lackluster wood-carved stiffness. That the characters come off as puppets even though they're not is perhaps intended to be ironic, given the artifice of film entire, & the threat of becoming automata. I can't help but feel there is greater irony in Quay films that assume humanity to puppets, than in a film that moves its actors in such lackluster wood-carved stiffness.

The lives, lusts, & loves of these characters just don't register as more than pictures. And had it been a picture-book instead of a feature film, almost anyone would've thumbed through it in ten minutes & that would've been enough.

The undeniable visual beauty of the thing is not sufficient in itself to carry an hour & a half of staring at pretty pictures that pretend to weightiness of meaning but are only decorations.

It all climaxes in a pretty little festival of surrealism in silvered darkness; fun & st range, but not half enough to make up for the empty portentious tedium that preceeds the decent if imperfect end.

And for a film partly about its music, it has an ineffective soundtrack ill-used throughout. A better score just might've saved it, but we'll never know. The brothers Quay are geniuses, but this film doesn't quite prove it.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

If there's a plot, to outline it would sound silly, much as would Eraserhead (1977), but it somehow functions in the manner of a dream, a work of considerable beauty & suggestiveness.

If there's a plot, to outline it would sound silly, much as would Eraserhead (1977), but it somehow functions in the manner of a dream, a work of considerable beauty & suggestiveness.

When the occasional great moment burst forth in The Piano Tuner, it's inevitably at moments similar to their films without live-action players, as when we glimpse a stop motion figure in the woods chopping down a tree; or the images of the eerie automated music boxes.

When the occasional great moment burst forth in The Piano Tuner, it's inevitably at moments similar to their films without live-action players, as when we glimpse a stop motion figure in the woods chopping down a tree; or the images of the eerie automated music boxes. That the characters come off as puppets even though they're not is perhaps intended to be ironic, given the artifice of film entire, & the threat of becoming automata. I can't help but feel there is greater irony in Quay films that assume humanity to puppets, than in a film that moves its actors in such lackluster wood-carved stiffness.

That the characters come off as puppets even though they're not is perhaps intended to be ironic, given the artifice of film entire, & the threat of becoming automata. I can't help but feel there is greater irony in Quay films that assume humanity to puppets, than in a film that moves its actors in such lackluster wood-carved stiffness.