Intergender Casting in Chinese Cinema

with special focus on the performances of Ivy Ling Po

Cheng Pei-pei is mistaken for a young man in the otherwise rather credible story Come Drink with Me (Dai zyu zi, 1966), despite that she's one of the most beautiful woman the earth has ever known.

Cheng Pei-pei is mistaken for a young man in the otherwise rather credible story Come Drink with Me (Dai zyu zi, 1966), despite that she's one of the most beautiful woman the earth has ever known.

Even more startling, perhaps, is the fact that such a beauty as Cheng Pei-pei should have been cast in her first really big role as a young man in The Lotus Lamp (Bai liang den, 1963).

Surprisingly enough The Lotus Lamp role was intended for Ivy Ling Po (who ended up dubbing the singing anyway). Surprisingly enough The Lotus Lamp role was intended for Ivy Ling Po (who ended up dubbing the singing anyway).

But Lin Dai, the putative star of the film, was having a crisis in her acting career & was frightened of Ivy's sudden popularity which would inevitably upstage her performance.

She threatened to leave the production entirely, resulting in then-unknown Cheng Pei-pei getting Ivy's male-impersonation role. The insecure Lin Dai, at one time one of the most famous actresses throughout Asia, would eventually commit suicide.

Like Cheng Pei-pei in Come Drink with Me, the petite & athletic Shih Szu appears in the title role of The Young Avenger (Xiao du long, 1972) as a swordswoman who for several scenes is mistaken for a young man. We're supposed to accept this as a possibility even though she's such a beautiful young woman she makes the typical Miss America contest winner look like she's been in a horrible accident.

Similarly in The Golden Seal (Jin yin chao, 1971) Ping Wang plays a rebellious young woman who to get away once in a while disguises herself as a beggar-boy or wandering young man, who in reality could no more pass for male than could the same film's busty cave-girl in a bathing suit.

There's almost never a good excuse for this lapse into purposeless impossibility of mistaking such beautiful women for men. Such moments in these swordswomen films force the viewers to fill-in & make excuses, like it's true barely pubescent boys sometimes look like beautiful women, & women like newly pubescent boys. But excuse is all it is, because Cheng Pei-pei as Golden Swallow & Shih Szu as the Young Avenger & Ping Wang in The Golden Seal just can't be mistaken for boys.

It's just something that recurs in wuxia or kung fu costume action films & as fans of the genre we have to accept it since nothing we say about it will change it. Now & then, as when the beautiful Brigitte Lin plays one of the mighty Three Swordsmen (Dao jian xiao, 1994) & is the coolest of transsexual swordsmen in Swordsman II (Xiao ao jiang hu zhi dong fang bu bai, 1992, it's possible to adjust to the unusual casting because the performance is so good & we just go with the character flow.

And when Ivy Ling Po was at her most popular in her male scholar roles of the 1960s, it has been asserted that viewers in Australia thought she really was a man, even if an awfully girlish one. Though it's hard for me to quite imagine how audiences could have thought so, it's true at least that Ivy created stylish "man mannerisms" & had a unique face not associated with "average" film beauties.

It's perhaps easier to go along with such casting if there happens to be an actress playing a swordsman or scholar. But when she's playing a swordswoman & is temporarily mistaken for a man with no actual physical disguise changing from scene to scene, this begs us as viewers to accept the possibility that everyone she encounters is blind as a bat & probably deaf as well, whether or not she bursts into a feminine-voiced opera song.

How it came about that so many directors came so easily to embrace this bit of oddity, & how film audiences so easily let filmmakers get away with it without laughing their arses off at these movies, may well have its origin in the cultural arts. In the various schools of Chinese, men frequently play all the roles, including great fighting heroines of the Sung Dynasty, the purpose being to keep men & women from being on the stage together.

How it came about that so many directors came so easily to embrace this bit of oddity, & how film audiences so easily let filmmakers get away with it without laughing their arses off at these movies, may well have its origin in the cultural arts. In the various schools of Chinese, men frequently play all the roles, including great fighting heroines of the Sung Dynasty, the purpose being to keep men & women from being on the stage together.

Elsetimes in some of these opera troupes -- in Yue Opera most notably -- it is women who play all the lead roles, including famous male generals, or love-struck scholars. And while the Beijing Opera has been integrated for men & women performers since the influence of "women hold up half the sky" sentiments of the Communist revolution, fans of Yue Opera have been extremely reluctant to support the idea that women should not play all the roles, & the Communist government's desire to "reform" Yue Opera meets with more ferocious protest than Chinese citizens can muster for their own fundamental human rights.

When some of these sorts of troupes became integrated with both men & women stars allowed to appear on the stage together, the casting methods never quite disappeared, with the style of male playing female, & female playing male, being distinct enough to have its own following, leaving every option open for casting that is not so much unusual as traditional.

Today traditionalists lament the vanishing of the gender-bent casting, which is no longer the standard method but more a nostalgic thing when it happens. As Chinese audiences become more interested in naturalism in casting rather than complete artifice, the influence of casting in "old school" wuxia has begun to look as improbable to Asian audiences as it does to western film fans, but at least the Asian audiences have some awareness that it's an old thing rather than a crazy thing.

Traditional opera is not the only source of gender-bent images of the heroes & heroines of history & legend. The beloved Goddess of Mercy Kwan Yin was once a mortal monk, & is most commonly depicted in art as a beautiful woman without breasts. A Ph.D. dissertation could be composed on gender cross-overs in Chinese art. But for cinema in particular, the primary modern influence has been the opera stage with its peasant-appeal of love-stories, hero tales, & fairy tales, & musically presented dialogue with a set number of folk-music melodies borrowed & formalized from "tea picking songs" or field laborers.

Europe had a similar theatrical history in that Shakespeare in his lifetime never saw an actual woman play any role he wrote for women played by women, & audiences swooned not for a male Romeo & female Juliette, but for a couple good looking lads pretending.

And while on the one hand this sort of casting was due to the limited rights of women & the fear of women's sexuality on theatrical display, this fear arose from the actual sexiness of the stage events, not to keep the sexiness from happening.

If you look closely at how Shakespeare wrote the women's roles, you'll find a powerful element of burlesque even in such a serious play as Henry V -- read the queen's routine about her various body parts with the realization that some beautiful lad did this for London audiences & the burlesque is obvious.

The histories are parallel East & West, but the difference here is that in the West such casting traditions died out long, long ago except as the most extreme of novelties, whereas such casting remains to this day normal among some of the Chinese troupes that continue to resist reform.

In more libertine or decadent times in Chinese cities (no less than in Paris) all-women theaters existed as part of bordello culture, the higher more refined part of the sex industry requiring its odalisques to be well-rounded entertainers, not just creatures to screw for pay.

Not to diminish the horrors of the lower end of the sex trade at nearly all points of history, in its upper echelons an odalisques took only what lovers she desired & who could afford a very high level of support, & a wealthy man would be in a particular strong position of prestige to be the sole support of such a fashionable odalisques whose fame could rise to superstar status in plays & fashion displays.

This older origin of women's theater is frequently left out of the histories. Officially men "always" dominated the stage until women asserted their rights, & Yue Opera as a specific example arose in the early 20th Century so that women could participate in an artform that was formerly all men. So too the all-male kabuki theater in Japan was in actuality founded by a Shinto nun named Okuni who specialized in male roles & whose entire troupe were on one level or another prostitutes.

When Okuni realized that male prostitutes were also very popular, she had the novel idea of adding female impersonators to her troupe. The appeal of girls dressed as boys & boys dressed as girls for the samurai class won the same fearful response from the government as outright revolution.

The government at first passed laws requiring wakashu (young male players) to cut their forelocks so that they would look less like girls, which had the effect of causing women generally, like the wakashu, to wear a headscarf in such a manner that no one would know if the forelock were shaved or not.

By degrees women were eventually banned, & the only kabuki stars who weren't at some risk of arrest were middle aged men who without appallingly thick make-up performing some distance away on a stage were not likely to be bigshots in the sex trade.

So too in various cities from Mongolia to Singapore & all parts in between, Chinese Opera frequently fell into ill repute, & in any era when prostitution was constantly assaulted by the government, the opera also fell into decline.

One recurring theory as to how men came temporarily to dominate the various Chinese opera schools in the 19th Century was because the earlier theaters had become such dens of licentiousness that actresses were at constant risk of rape. This isn't likely to have been the case at all, & the women & young men who turned tricks on dark streets or behind hedgerows or in tattered puptents alongside streams were at vastly greater risk of rape or murder than ever were those who were protected within the system of theatrical training & exhibition.

But the myth that even the upper echelons of the sex trade were violent & horrifying provided a nice excuse (whether in Elizabethan England, early Tokugawa Japan, or revolutionary China) to come down hard on the sex trade & most especially that portion which came to be viewed as fashionable by the common masses. The diseased straw-mat trade was safer from government persecution because that which thrived in the realm of fear & disease was no threat to tyranny.

The significance of sex & sexuality having always been associated with these gender-bender roles is important to understand in order to correct a too-often repeated idea that single-gendered stage performances arose to keep them from being sexual. They were very sexual. They were also very homosexual, a reality investigated with deep emotional honesty in Kaige Chen's epic masterpiece Farewell My Concubine (Ba wang bie ji, 1993).

But the great thing about gender ambiguity is that it can be anything to anyone. It can often slip by censors because the claim can be made that any appearance of impropriety is actually totally sexless. So for children & frightened censors alike, it's totally innocent & naive.

For straight members of the audience, especially young girls, it's a way to display overt & anguished crushes on some "guy" without any threatening aspect attached. At the same time, for the gay minority watching the film (or stage play), it's gay icon time in a big way. No matter the viewer's response, it is sexy-sexy for anyone who wants it to be. It's no such thing for whoever prefers it not to be.

This historical discussion has many ramifications & makes a good background understanding for several aspects of Chinese cinema. But I want for this moment to discuss the career of Ivy Ling Po, a great swordswoman of the cinema, & before that a player of male roles in popular period love stories based on Huangme Opera folktales & romances. This historical discussion has many ramifications & makes a good background understanding for several aspects of Chinese cinema. But I want for this moment to discuss the career of Ivy Ling Po, a great swordswoman of the cinema, & before that a player of male roles in popular period love stories based on Huangme Opera folktales & romances.

Understanding her highly successful career provides one enormous doorway into understanding, perhaps even embracing, the unusual casting that was commonplace in the 1960s, had strong lingering effects right through the 1970s, & even today persists to some degree.

In the 1950s folk opera plays done as dialect films were popular in rural China. A twelve to fifteen year old actress then billed as Xiao Yuan, later to be known as Ivy Ling Po, appeared in many of these of the Hokkien dialect, her very first in 1951. Plus she was the actual voice for other stars who lacked her singing talent, & the first time she showed up at Shaw Brothers was to dub some of the singing for the opera-based Dream Of The Red Chamber (Hong lu meng, 1962; not coincidentally she had played in a Hokkien dialect film version of this story in 1956, & would have a role in a 1978 remake shortly before her temporary reitirement to raise a famiy in Canada).

At this time she was spotted by director Han-hsiang Li, who gave her a starring role in The Love Eterne (Liang Shan Ba yu Zhu Ying Tai, 1962). Quite often her official filmography starts with The Love Eterne even though she'd been in forty or more films of the 1950s. In the Shaw Brothers film she played "Brother Liang," & was the male love interest for Zhu Yingtai played by the beautiful Betty Ling Po, a well established leading lady.

After the film's release, Ivy became an instant celebrity, mobbed at airports by admirers of all sexes, receiving thousands upon thousands of love letters from teenage girls, & even marriage proposals from lovestruck wealthy dowagers.

Ivy as the young scholar Bo Liang made such an enormous impact on the public that the second annual Golden Horse Awards came close to controversy not knowing if she should be awarded Best Actress or Best Actor award. They came up with a new category, Outstanding Performance, & would give her the Best Actress award the following year at the Asian Film Festival.

Not only does Ivy play a male character The Love Eterne, but her co-star Betty wonderfully enough plays a maiden who Yentl-like must disguise herself as a boy in order to study as a scholar. Not only does Ivy play a male character The Love Eterne, but her co-star Betty wonderfully enough plays a maiden who Yentl-like must disguise herself as a boy in order to study as a scholar.

When she falls in love with Liang, the matter is complicated by their already having become "sworn brothers." Only by posing as her own twin sister can she make her feelings known.

As in Yentl Brother Liang is attracted to his sworn brother with obvious sexual tension even before "he" realizes the other "he" is a she. There's quite a touching sequence when Liang realizes his best friend is a girl & it's all right to be in love with him/her. But does this really negate the homosexual subtext that led to that moment? There is a distinct charm to the idea of loving someone for their individuality rather than because they're sex-appropriate.

There's the clear implication that the sworn brothers would've happily lived together as lovers forever even if both really were men, if society would permit it, but as it turns out one of them is a woman, that's not a disappointment because it means their love can be legitimized. That both are boys, but one is not a boy, but in the greater reality of the casting neither are boys, makes for a whimsical yet profound "harmony of dissonance" where gender is concerned. These are honestly androgynous characters capable of deep abiding love for each other without regard for their gender orientation, & any problems imposed are societal, not biological.

As an added whimsical aside, you may get a small giggle if you notice that in classroom sequences, most of the other "boys" are also played by male impersonators, though it is not supposed to imply that schools in those days were dominated by Yentl types.

In such tales there are only rarely happy endings & this one's tragic & bittersweet ending may dissatisfy western viewers unprepared for a light romantic comedy to end in star melodrama.

As these tragic-end comedies look so much like lesbian stories it's tempting to compare them to American pulp novels about lesbians from the 1950s & 1960s, in which the butch woman of the couple usually dies & the femme goes straight marrying someone else. Dropping dead, often from suicide, provides the "moral lesson" which in turn excuses the sexploitation of the book up to that redeeming moment of death to one & proper marriage to the other.

Despite the similarity of structure, these Chinese operas have a different cultural center & do not mean to comment on homosexuality as a sin that requires repentance of the least abnormal in the pair & death to the most abnormal. Rather, in a repressed society where arranged marriages were standard but marriage for love was unheard of, the fantasy of the ideal love is punished not because of the homosexual subtext created by the casting, but because of the heterosexual primary text.

If they were allowed a happy ending, before you know it actual sons & daughters were would be demanding to marry for love rather than because their parents arranged it. And the decline of such entertainment is at least partially due to the fading belief in arranged marriages as inevitable & necessary.

The original stage operas were ultimately not cast single-sex in order to distance the characters from the threat, in a repressed society, of "real" sex being implied, but "real" romance itself. The unhappy endings excused not so much the sexiness of the plays' implications, but the threat to the repressed & repressive social order which did not permit even an innocent affair outside the protocol of arranged marriages.

But by the time this traditional casting found its way into cinema, it was increasingly for the novelty factor & the sexiness of women in medieval drag. The romantic appeal is doubled in The Love Eterne by having even the "femme" of the couple passing as male. And if such films did in fact release a certain tension for gay filmgoers among opera attendees, & have special meaning to gay audiences, that was never the primary intention or you can bet your red britches there'd've been as many martyrs as there were actors.

Often in such opera stories, when they found their way to film, the lead players are only lip syncing songs sung by someone else. But Ivy had a beautiful voice for such songs.

Often in such opera stories, when they found their way to film, the lead players are only lip syncing songs sung by someone else. But Ivy had a beautiful voice for such songs.

You won't have to be a big fan of Chinese Opera to like her singing in The Love Eterne, one of the best films of its kind on every level, including the singing. If you don't like Ivy's musical skills in this film, you might as well forget seeing any more of them.

The Yue Opera today, so far, still adheres to these traditions, but probably would not thrive without a degree of state support & other hand-outs.

The cinematic musical adaptations were already fading away before the end of the 1960s as of huge commercial consequence, though even when the fad for these films was long gone there'd occasionally be a new all-out-opera retro-film like Wu Yen (Chung mo yim, 2001).

In Wu Yen Anita Mui as the Emperor Qi has a rousing pair of romances with the bandit-princess played by Sammi Cheng & the fox-fairy played by Cecilia Cheung, while the Fox herself frequently disguises herself as a man in order to pursue her deeper love for the bandit-princess.

This is truly a throwback to days of Ivy Ling Po's status as a superstar, & Anita Mui's performance to great extent is patterned on Ivy's method. The humor is very effective, the performances charming as all hell, & the sensuality of the genderphuck eroticism is more overt than was possible in the 1960s. In the main, though, Wu Yen was a totally effective revival of an older manner of storytelling in film.

So the continuing possibilities for such entertainment has never ended. Ivy herself came out of retirement in 2002 to star in a musical stage version of her classic Brother Liang role, & continued for the next few years to play this role on stage or perform in concerts, to sell out audiences in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Sydney, Vancouver B.C., & elsewhere.

Ivy again plays a guy in A Maid from Heaven (Qi xian nu, 1963) in which she again as Bo Liang sings "his" seductions to Fang Ying, who plays the Seventh Daughter of the King of Heaven, in love with a mortal man. The stage design is very pretty & fantastical with what certainly looks like some visual influences from The Wizard of Oz (1939). The songs are a delight & Ivy never looked more happily boyish.

Ivy again plays a guy in A Maid from Heaven (Qi xian nu, 1963) in which she again as Bo Liang sings "his" seductions to Fang Ying, who plays the Seventh Daughter of the King of Heaven, in love with a mortal man. The stage design is very pretty & fantastical with what certainly looks like some visual influences from The Wizard of Oz (1939). The songs are a delight & Ivy never looked more happily boyish.

A Maid from Heaven is in keeping with that tradition of unhappy endings in opera tales, despite that by & large the bulk of the story is happy-lovey-upbeat, full of pleasant tunes & pretty poses. A Maid from Heaven like The Love Eterne is well budgeted & beautifully filmed. Anyone who can adjust to the idea that dialogue is sung throughout will find both of these Brother Liang films a delight.

A third example of the Shaw Brothers opera musicals featuring Ivy Ling Po in the male lead is the fantasy tale of The Mermaid (Yu mei ren, 1965), a tale that goes against the usual requirement for a maudlin ending. A third example of the Shaw Brothers opera musicals featuring Ivy Ling Po in the male lead is the fantasy tale of The Mermaid (Yu mei ren, 1965), a tale that goes against the usual requirement for a maudlin ending.

As had happened for her Golden Horse Award a couple years earlier, the Asian Film Festival required a special category in order to not deprive a woman in a female role of an award. Ivy received the gender-non-specific Most Versatile Talent Award for her performance in The Mermaid.

In this folk tale, a carp-spirit turns into a beautiful maiden who loves the young scholar Zhang Zhen played by Ivy. Ching Lee (or Li Chin) who plays the carp-girl simultaneously plays the daughter of a stuck-up famiy that rejected the scholar as a proper suitor.

That the nice carp-girl & the snotty wealthy maiden look identical causes some complications on the road to a happy ending, though intervention of a Goddess will be required to assure an ending unlike most Huangmei opera stories, which usually end in tragic melodrama. That the nice carp-girl & the snotty wealthy maiden look identical causes some complications on the road to a happy ending, though intervention of a Goddess will be required to assure an ending unlike most Huangmei opera stories, which usually end in tragic melodrama.

In 1965 Shaw Brothers studio pressured Ivy into getting a nose job, & she was a more "standard" beauty after that less convincing in her male roles.

But for all intent & purposes the popularity of male impersonation films was waning by 1966, & with a couple exceptions Ivy would be playing other sorts of roles thereafter, especially swordswoman roles.

The Mirror & the Lichee (Xin chen san wu niang, 1966) shows her new nose in a male role which was to be her last for a couple of years. She is once again the poor scholar in love, wooing Ying Feng.

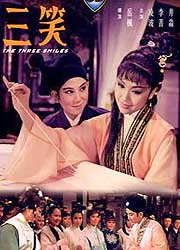

She would reprise her well-famed male impersonation once more, in what would be the last important Huangmei opera film from Shaw, The Three Smiles (San xiao, 1969).

She would reprise her well-famed male impersonation once more, in what would be the last important Huangmei opera film from Shaw, The Three Smiles (San xiao, 1969).

After seeing her smile at him three times, Brother Ting (Ivy) is crazily in love with Autumn Fragrance (Ching Lee, her co-star in The Mermaid), & sells himself into servitude in order to remain near her & pine.

The craze for "Yellow Plum" opera movies had faded & wouldn't've lasted until 1969 without Ivy's popularity.

Even she had not appeared in huangme opera film since The Mirror & the Lichee three years earlier, so The Three Smiles was something of a belated last hurrah, & a fond farewell to the type of role the public had long most loved from her. Even she had not appeared in huangme opera film since The Mirror & the Lichee three years earlier, so The Three Smiles was something of a belated last hurrah, & a fond farewell to the type of role the public had long most loved from her.

For most of the 1960s a selection of some of cinema's most stunning beauties were selected for Ivy to sing to & woo. But at long last rigid familiarity of the plot structure, & sameness of the tunes, had finally worn out their welcome with the public.

As Ivy had been very nearly typecast in these roles, it could've meant the end of her career, except she was in fact so beautiful she could make an easy transition into any sort of roles she preferred, & was regularly praised for her amazing versatility.

So while the majority of her hit films featured her in male roles, there were always exceptions. Her scholar characters being in the main comedic tended to be a mite flighty or goofy in the head. They were fluffy tales despite the overblown tragedies enacted in the climaxes of so many of those films. Yet her "straight" roles were highly dramatic.

She made a few nearly socially relevant dramas. Song of Tomorrow (Ming ri zhi ge, 1967) is about a dance hostess (Ivy) in love with a jazz musician (Chiao Chuang) whom she struggles to save from drug addicton. The Silent Love (Ya ba yu xin niang, 1970) is a tragedy about a mute man (Chin Feng) in love with a woman (Ivy) who is abused by her husband (Chang Pei Shan). She made a few nearly socially relevant dramas. Song of Tomorrow (Ming ri zhi ge, 1967) is about a dance hostess (Ivy) in love with a jazz musician (Chiao Chuang) whom she struggles to save from drug addicton. The Silent Love (Ya ba yu xin niang, 1970) is a tragedy about a mute man (Chin Feng) in love with a woman (Ivy) who is abused by her husband (Chang Pei Shan).

In The Younger Generation (Er nu shi wo men de, 1970) Ivy plays a young woman who gives up her family to run off with her lover. They live a lovers' idyll for some while & establish a family of their own, but eventually have a three-hanky-weeper of a downfall, perhaps as a lesson for "the younger generation" who mistakenly believed love trumps filial obligation.

In the high-drama Too Late for Love (Feng huo wan li quing, 1966) she plays a tubercular wife struggling during wartorn years, sweeping major awards for its year of release. For this performance she received the Best Actress Golden Horse Award.

In A Cause to Kill (Sha ji, 1970) Ivy broke entirely from romances to play a film-noirish femme fatale, embodied by a modern day housewife with cause to kill her husband.

In A Cause to Kill (Sha ji, 1970) Ivy broke entirely from romances to play a film-noirish femme fatale, embodied by a modern day housewife with cause to kill her husband.

These comparatively "normal" roles didn't sell Ivy Ling Po to the public with quite the same high degree of success as when she was playing gentle male scholars. The 1970s in particular were a difficult transition point for many actresses who'd been the biggest box office in the 1960s when films were pitched, by & large, to girls & women.

In the 1970s they were pitched more to young men with the rise of "macho" tales of "the martial world." These were "the next big thang" & if actresses were to stay on top they'd have to fit into these roles.

Cheng Pei-pei had set the standard for how actresses could stay on top in the new "martial world" cinema, practically instigating the new direction in cinema with Come Drink with Me.

Ivy well knew she, too, could play such roles, having already been a "wuxia heroine," the swordswoman-in-red in Temple of the Red Lotus (Hu shao hong lian si zhi jiang hu qi xia, 1965), though it was scarcely more than a support role.

She'd play increasing numbers of swordswoman roles after Huangme fad was over. She is the mysterious swordswoman in The Mighty One (Tong zi gong, 1971), the one-armed swordswoman of The Crimson Charm (Xie fu men, 1971), the "good" martial sorceress in Finger of Doom (Tai yin zhi, 1971), the top fighter among the Sung epic The Fourteen Amazons (Shi si nu ying hao, 1972), & many similar roles.

Clearly Ivy Ling Po had weathered the changes at Shaw Brothers with her career intact, & would eventually become a producer in her own right, a critical player in the "new wave" supernatural wuxia of the 1980s & early 90s when she produced Golden Swallow (Gam yin ji, 1987).

To some degree such swordswoman performances can be viewed as "intermediate gender" roles in themselves. At any rate, for younger film goers, this was the type of role Ivy would be noted for, though for slightly older film goers she would always be, at heart, Brother Liang.

Two of her characters are not fully male roles but kind of "bridge" the gender-bender possibilities by having a female character disguising herself as a male. Two of her characters are not fully male roles but kind of "bridge" the gender-bender possibilities by having a female character disguising herself as a male.

Ivy did this for comedic romance in The Female Prince (Shuang feng ji yuan, 1964) & for heroic effect in the vastly more serious musical The Lady General Hwa Mu Lan (Hua Mu Lan, 1964).

In The Female Prince, complicated family situations lead to Feng-hsiao Ching (Ivy) disguising herself as her own husband (otherwise played by her real-life husband & frequent co-star, Han Chin), who has been unjustly imprisoned.

In disguise she heads off for the capital, where she ends up participating in the national Confucian scholar examination, doing quite well, leading eventually to a comedic romance with the Emperor's daughter.

In The Lady General Hua Mu Lan Ivy plays Mu Lan the famous Chinese heroine who dressed in soldierly armor & set off to defend her nation in War. In The Lady General Hua Mu Lan Ivy plays Mu Lan the famous Chinese heroine who dressed in soldierly armor & set off to defend her nation in War.

She falls in love with General Li (Ivy's actual husband again, Han Chin) but dares not reveal her true gender or her feelings. She ends up being offered the general's daughter's hand in marriage.

The music is typical of the genre & surprisingly enjoyable, though somewhat indistinguishable one song to the next, or even one film to the next, being always based on the same few folk melodies. The costumes are gorgeous.

But the attempt to have a big battle climax overreaches. It's not just a stagey opera battle but attempts to look like the real early medieval warfare, though in 1964 Shaw Brothers studio had not yet gotten mass-battle-sequences down pat.

Someone unfamiliar with this unusual & operatic genre might like The Lady General best as a "sample" of the form, quite a good example of the folk-opera sound, & way better costuming for Ivy than when she does her more typical "scholar drag" in several films.

The character of Mu Lan has as her "excuse" for crossdressing & going into battle the fact that her country needs defending & her father is too ill to defend it. Within the Confucian context she cannot seek unwomanly things like warrior pride, but gets around the restrictions on her career opportunities by framing it as filial necessity.

Yet the fact is, right from the start of the story, Mu Lan is obviously bored by girlish things, does not look forward to the prospect of marriage, & wants to go into the world & have adventures. She's quite a great character really, & she just looks so damned good suited up for battle.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

Surprisingly enough The Lotus Lamp role was intended for Ivy Ling Po (who ended up dubbing the singing anyway).

Surprisingly enough The Lotus Lamp role was intended for Ivy Ling Po (who ended up dubbing the singing anyway).

That the nice carp-girl & the snotty wealthy maiden look identical causes some complications on the road to a happy ending, though intervention of a Goddess will be required to assure an ending unlike most Huangmei opera stories, which usually end in tragic melodrama.

That the nice carp-girl & the snotty wealthy maiden look identical causes some complications on the road to a happy ending, though intervention of a Goddess will be required to assure an ending unlike most Huangmei opera stories, which usually end in tragic melodrama.

Even she had not appeared in huangme opera film since The Mirror & the Lichee three years earlier, so The Three Smiles was something of a belated last hurrah, & a fond farewell to the type of role the public had long most loved from her.

Even she had not appeared in huangme opera film since The Mirror & the Lichee three years earlier, so The Three Smiles was something of a belated last hurrah, & a fond farewell to the type of role the public had long most loved from her.