Part I: Jirocho of Shimizu, His Life & Early Films

One historical yakuza boss was Jirocho of Shimizu (1820-1893), born of the merchant class. One historical yakuza boss was Jirocho of Shimizu (1820-1893), born of the merchant class.

The 1868 Restoration pretty much put an end to yakuza rule of the highways. But Jirocho, with a combination political acumen & an authentic reputation for chivalry, was able to move out of the crime world into a position of respect & honor in his native Shimizu.

He helped establish the first English language school in the region, & because even in his "honest" later life he was a "secret boss" of dock laborers of Shimizu Harbor, the government entrusted him semi-officially with the safe landing of the S.S. Ulysses S. Grant in 1877.

One of the earliest versions of his life to make it to the screen was in the silent era, & which still survives, was the Shimizu Jirocho Trilogy (Nikkatsu, 1927-1928) directed by Yoshiro (Kichiro) Tsuji.

Starring in the title role was Goro Kawabe, a popular action star. A still from this silent version of Jirocho's adventures is shown near this paragraph, above right.

As one of the earliest popular subjects for cinema, lost silent versions begin with Shimizu no Jirocho (Yokota Sakai, 1911) directed by Shozo Makino (1878-1929), starring kabuki-style actor Matsunosuke Onoe in the title role.

Onoe was Japan's first big film star. He played Jirocho in several films after Shozo Makino's early version. A director as Nikkatsu Tokyo starred him in a pair of films Shimizu Jirocho zenpen (1924) & Shimizu Jirocho kohen (1924), & followed up with another Jirocho film pair, Rakka no mai zenpen (1925) &Rakka no mai: chuhen (1925). Onoe was Japan's first big film star. He played Jirocho in several films after Shozo Makino's early version. A director as Nikkatsu Tokyo starred him in a pair of films Shimizu Jirocho zenpen (1924) & Shimizu Jirocho kohen (1924), & followed up with another Jirocho film pair, Rakka no mai zenpen (1925) &Rakka no mai: chuhen (1925).

Unfortunately, though Onoe made about 1,000 films in his career, almost none of them survive, & no Jirocho film is among those few.

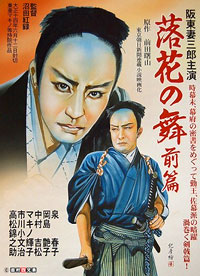

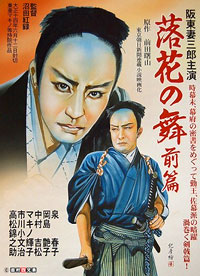

Simultaneous with the Nikkatsu Rakka no mai films directed by Tomiyasu Ikeda & starring Onoe, Shozo Makino's own film company made the same story Rakka no mai zenpen (Dance of the Falling Petals I, Mao Makino Tojin, 1925) & Rakka no mai kohen (Dance of the Falling Petals Part II, Tao Makino Tojin, 1925), with Koroku Nomata directing an all-star cast.

These starred Kobunji Ichikawa as Jirocho, Tsumasaburo Bando as Tetsuta, & Ryunosuke Tsukigata as Omasa, big stars all. A colorful poster for Koroku Nomata's version of Rakka no mai is reproduced with this article. The title is from a famous poem & enka folksong, with falling petals being a standard illusion to the ephemerality of life, in particular the lives of the soldiers.

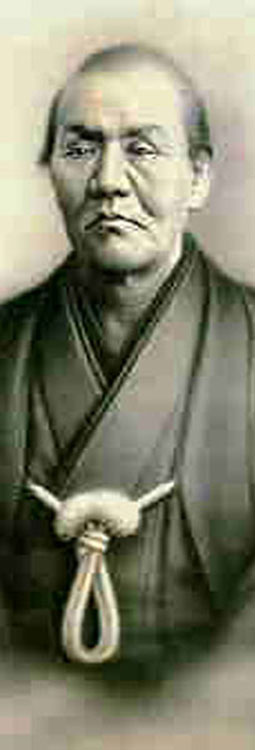

Shozo Makino, whose portrait is reproduced at the left, remade the film for Nikkatsu Kyoto, with the same star, in 1916. Later still, in 1923, he made a six-reel version for his own company Makino Kyoiku, co-directed with Koroku Numata. Shozo Makino, whose portrait is reproduced at the left, remade the film for Nikkatsu Kyoto, with the same star, in 1916. Later still, in 1923, he made a six-reel version for his own company Makino Kyoiku, co-directed with Koroku Numata.

None of these, alas, survive, & probably only the 1923 film would be of more than academic interest if we had it, as it was the longest, from a time when Shozo was beginning to "modernize" somewhat his approach.

Those lost early silents drew their inspiration from theater tradition & were hardly more than kabukiesque tableaus of one-reel lengths. The stage & films created a legend but Jirocho's true history was ready-made for elaboration. This theatrical tradition began in Jirocho's lifetime, when his friend, educator & poet Amada Goro (1854-1904), wrote Tokai yukuden (Tales of Chivalrous Men of the Tokai Region, 1884).

Jirocho was not literate & could not read the book about himself & his merry-men, but supported the book's publication by purchasing 200 copies in advance, to be distributed among friends, politicians, & visitors to his estate. Portion's of Goro's chronicles were circulating in manuscripts as early as 1879, & almost immediately stage plays & kodan storyteller repertoirs expanded into themes of Jirocho's abject bravery.

Shozo was the first important Japanese film director, basing his earliest films about Jirocho on tales from a kodan story collection by Jirocho-den by Kanda Hakukzan III (1872-1932). Many other silent directors were also issuing their versions of Jirocho's life. Such films from the 'teens tended to be merely pictorial & not too specific as to plot, so that the benshi or silent film narrators could tell whatever Jirocho story they already had in their repertoir.

Only in the 'twenties did the power of the benshis begin to diminish, & then longer more elaborately plotted films began to appear, including Hotei Nomura's Shimizu no Jirochi (Jirocho of Shimizu, Shochiku Kamata, 1922).

Shozo's son, Masahiro Makino (1898-1993), was one of the great pioneers of jidai-geki -- together they are the father & grandfather of jidai-geki -- & Masahiro would direct more films about Jirocho than any other single director, beginning with another lost film, Jirocho hadaka-tabi (Jirocho's Naked Journey, Makino Talkie Seisaku-jo, 1936) starring Shinjiro Asano.

Masahiro's next excursion into Jirocho territory was Shimizu Minato (Shimizu Harbor, Nikkatsu, 1939). Once more the film does not survive, but its immediate sequel does, Zoku Shimizu Minato; aka, Shimizu minato daisan yume dochu (Shimizu Harbor Concluded, Nikkatsu, 1940).

Cheizo Kataoka plays Katsuhiko, a young man who owns a vintage record with a song (performed by Rokuro Nukada) about enshrining the sword of Ishimatsu, Jirocho's chief lieutenant. Chiezo falls asleep & dreams himself into Torazo's narrative. Jirocho is played by Takashi Ogawa, but this is a gaiden or "side-story" so it is really Ishimatsu's story.

He dreams he is himself Ishimatsu, at Shimizu Harbor preparing for his last gang battle. There are three songs performed during the film, & it set a standard for "singing samurai" or more appropriately "singing matatabi" films right into the 1960s.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

Onoe was Japan's first big film star. He played Jirocho in several films after Shozo Makino's early version. A director as Nikkatsu Tokyo starred him in a pair of films Shimizu Jirocho zenpen (1924) & Shimizu Jirocho kohen (1924), & followed up with another Jirocho film pair, Rakka no mai zenpen (1925) &Rakka no mai: chuhen (1925).

Onoe was Japan's first big film star. He played Jirocho in several films after Shozo Makino's early version. A director as Nikkatsu Tokyo starred him in a pair of films Shimizu Jirocho zenpen (1924) & Shimizu Jirocho kohen (1924), & followed up with another Jirocho film pair, Rakka no mai zenpen (1925) &Rakka no mai: chuhen (1925).