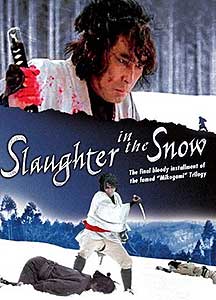

The toseinin or drifter, Jokichi of Mikogami (Yoshio Harada), is still on the trail of vengeance in Trail of Blood III: Slaughter in the Snow (Mushukunin Mikogami no Jokichi: Ko Kai Ni Senko Ga Hinda; aka, Mikogami no Jokichi: Tosagari no Senkoga Tonda, 1973), journeying along the Koshu highway, encountering rural yakuza at every village or station. He's seeking the final villain responsible for the murder of his family in the first of the three Trail of Blood films.

The toseinin or drifter, Jokichi of Mikogami (Yoshio Harada), is still on the trail of vengeance in Trail of Blood III: Slaughter in the Snow (Mushukunin Mikogami no Jokichi: Ko Kai Ni Senko Ga Hinda; aka, Mikogami no Jokichi: Tosagari no Senkoga Tonda, 1973), journeying along the Koshu highway, encountering rural yakuza at every village or station. He's seeking the final villain responsible for the murder of his family in the first of the three Trail of Blood films.

In Part I he killed Boss Kyubei & all his men. In Part II he killed Boss Chogoro & all his men. He has only one great foe less, Boss Chuji, who among Japanese folk heroes is a figure like Robin Hood.

The idea of Chuji being a villain hunted down by Jokichi would be quite a radical conclusion to the trilogy. This would be like having Rob Roy out to kill an evil Robin Hood; or Wild Bill Hickok out to kill an evil Wyatt Earp.

Yet for symmetry's sake, it does seem like the third film should be about killing Chuji & all his men. Which just doesn't happen.

We don't even get a hint of an explanation why Chuji is such a bad guy when he is a legendary chivalrous gambler in scores of books, plays, & films, generally championing the weak. We'd be correct to surmise that the reason Chuji doesn't show up for a final showdown is that this was not actually planned as a trilogy. There'd been some hope of a fourth film in an ongoing saga, so the ultimate foe to be kept at a distance.

Chuji (played by Ryunosuke Minegishi in the previous film) doesn't even appear in Part III at all. Chuji (played by Ryunosuke Minegishi in the previous film) doesn't even appear in Part III at all.

He is Jokichi's unachieved goal, an off-stage character who we know has hired the assassin "Windmill" Kobunji (Natsuyagi Isao, who was brilliant as the lead in Hideo Gosha's two Samurai Wolf films), for the express purpose of killing Jokichi.

So too the one-eyed wanderer of the first two films -- an ambiguous & imposing presence who always seems to suggest something more is going to happen than ever involves him -- is also missing from the final film.

Yet in spite of not following up on the loose ends & plot lines suggested in the earlier episodes, Slaughter in the Snow is an effective, a tale of superlative tragic machismo, & a rewarding film for anyone enamored of the matatabi-mono or wanderer-tale mythos of sword-slinging peasant drifters on the highways of old Japan.

The strengths of the film are sweepingly portrayed characters, intensely delivered one-liners & swift menacing exchanges, & graphic violence.

That a tale marked by carnage is exploitation may be true, but there is yet something of the artfilm about Jokichi's simple straightforward action & adventure. That a tale marked by carnage is exploitation may be true, but there is yet something of the artfilm about Jokichi's simple straightforward action & adventure.

As with Tomisaburo Wakayama's character of Ito Ogami in the Babycart movies, the excesses of spurting blood actually looks like red paint, probably intentionally so.

A stranger to Japanese cinema could be forgiven for not liking it, though in reality it is no more violent than a lot of acknowledged samurai classics. The protracted violence at the end of Sword of Doom (Daibosatsu toge, 1966), & the gruelling belly-puncturing scene with bamboo sword in Harakiri (Seppuku, 1962) are in fact more violent than anything in Jokichi's saga.

But these other films were in black & white & did not make use of the squirting blood routines first tried by Akira Kurosawa in Sanjuro (Tsubaki Sanjuro, 1962) & imitated by such directors as Kazuo Ikehiro & Kenji Misumi with straight-faced overkill.

The neophyte viewer who is overwhelmed & impressed by Harakiri's violence may be merely repulsed & dismayed by the full color geisers in the Trail of Blood films, the shock of it blinding some viewers to the grace & Romanticism of Jokichi in his grotesque yet aesthetic world.

The characters aray is thrilling. This is not to say they are deeply portrayed, but they are hugely portrayed. The man with the patch in the first two episodes, & Windmill Kobunji in the third, are, like Jokichi himself, intense figures, impressing by the flick of a wanderer's cape, a quirk, or an expression. The characters aray is thrilling. This is not to say they are deeply portrayed, but they are hugely portrayed. The man with the patch in the first two episodes, & Windmill Kobunji in the third, are, like Jokichi himself, intense figures, impressing by the flick of a wanderer's cape, a quirk, or an expression.

Medieval yakuza are expected to owe alligience to an oyabun or godfather, but wanderers within yakuza or gambler society are outcast among outcasts, belonging to no boss, having no home. If period yakuza films always feature an outsider as central hero, then the matatabi-mono sub-genre features the twice-outcast antil-hero.

But in the case of Jokichi, he approaches being an outright villain, albeit one we come close to understanding, one who does not intentionally hurt the innocent but doesn't help them either. He pursues personal vengeance & cares nothing about the larger nature of injustice, it being no one's place to seek justice for nor his place to seek revenge or provide succor for anyone else.

In Slaughter in the Snow, Jokichi is his by now familiar, extraordinarily unhappy, brooding self. His amoral code -- his rule never to meddle in the affiars of others, nor ask anyone's aid for himself -- is brutally conveyed in an early scene when he is eating a pheasant roasted out in the open.

In Slaughter in the Snow, Jokichi is his by now familiar, extraordinarily unhappy, brooding self. His amoral code -- his rule never to meddle in the affiars of others, nor ask anyone's aid for himself -- is brutally conveyed in an early scene when he is eating a pheasant roasted out in the open.

Nearby, some expansively creeply yakuza murder a cowardly samurai, then prepare to rape his surviving girlfriend (Michiyo Yasuda).

Jokichi would not have interferred in any manner, except that these men had the bad judgement to insist he go away. He refuses to have his meal interrupted & says, "You go away."

They attack him; they all die; & he walks away not otherwise showing how perturbed they made him. And the woman, angry that this powerful toseinin did not kill the men specifically for her sake, begins to follow Jokichi out of a curious need to know what the hell kind of man he really is.

By way of contrast we are introduced to Kobunji, who finds himself in a similar situation as witness to a drunken samurai about to rape a woman.

Kobunji challenges the drunkard & uses his cinematically photogenic if unrealistic knife-throwing technique, using a windmill wind-up before the throw, wounding the would-be rapist while the woman (Setsuko Ogawa) escapes. Then when the samurai hoots & hollars & roles around on the ground, Kobunji says, "Don't whimper. You won't die."

This event leads to repurcussions helpful to nobody involved, strongly implying that Jokichi's policy of never meddling is better.

In fact, however, Jokichi is attracted to Kobunji's character & nature, & does become a meddler against his better judgement. In fact, however, Jokichi is attracted to Kobunji's character & nature, & does become a meddler against his better judgement.

Having witnessed Kobunji's unusual talent, Jokichi finds himself in a brief conversation with the assassin, who as a professional killer is chagrined to have fought someone without pay.

Kobunji says, "Three days ago I was paid a lot to kill a man." Jokichi replies, "I pity the man marked by you." "Shall I tell you his name?" Kobunji asks, & adds: "Jokichi of Mikogami."

Kobunji is dying of consumption. He becomes a frightening, sickly, almost monstrous swordsman when attacked by the yakukza gang wanting to avenge the rapist-samurai who was their boss's yojimbo bodyguard. Violently coughing blood & staggering, barely able to breathe, Kobunji yet fights, however awkwardly, with horrific effectiveness, killing many of his attackers.

Jokichi, watching from a comfortable position, is still trying to live up to his intention not to meddle, but finds himself unable to resist. When he joins the fray a yakuza demands his name, but Jokichi shouts, "Haven't any!" as he's a man who barely exists.

It would seem he pities the terribly ill assassin, but what is more likely is that he felt challenged by Kobunji & would not let the assassin die until the two of them could have their own match. It would seem he pities the terribly ill assassin, but what is more likely is that he felt challenged by Kobunji & would not let the assassin die until the two of them could have their own match.

In the wake of the battle, Kobunji is too sick to move. He's cared for by Jokichi for many days. "A man who is going to be killed," says Kobunji, "nursing his killer. It's crazy."

The woman who has been following Jokichi is incensed to think her own pleas for help had been ignored, but he was willing to help a man paid to kill him. "It was beneath you to notice me but you helped Kobunji," she says angrilly. But her hatred turns to jealousy since she is in fact attracted to Jokichi. When she attempts a seduction, he scratches her as might a cat, with his razor-nailed, claw-like maimed hand.

She begins to suspect he's overly fond of Kobunji, but Jokichi answers her innuendo of homosexual interest with, "Don't let your imagination run wild. Even Kobunji knows I'm not doing it it out of kindness. We will fight it out."

And when that encounter does finally happen, Jokichi deflects the assassin's flying blade. And when that encounter does finally happen, Jokichi deflects the assassin's flying blade.

Then, before he can make his death-stroke, Kobunji falls to his knees & begs for his life -- not out of cowardice but because he wants to live long enough to help the kidnapped woman he had aided earlier in the film.

This proof of Kobunji's softness, his meddling do-gooder streak, disillusions Jokichi who kicks the begging man in the face. But Jokichi's similar (& unwanted) streak of softness forces him to let Kobunji live.

In the eventual climiactic scenes, Kobunji is near death from tuberculosis, gasping miserably for breath, but still fighting the kidnapping yakuza gang. With bitter irony, the the kidnapped woman has decided she likes living with the rich gamblintg boss, & Kobunji's chivalry has proven mightily misplaced.

Jokichi as usual would probably not interfer, especially having lost all regard for Kobunji due to his softness. But once again bad guys make an unprofitable decision to attack Jokichi.

The extended carnage, this amazing ballet of death, has at its core two men we have followed & on some level liked, so it has emotional impact as well as the beauty of its choreography. The extended carnage, this amazing ballet of death, has at its core two men we have followed & on some level liked, so it has emotional impact as well as the beauty of its choreography.

After the tremendous violence in the snowy hills winds down, it seems that Jokichi's strongest desire is to make Kobunji realize that he was an ass to go against his own rule never to kill except for pay, & like himself never to meddle in the villainies of others.

On his knees in the snow on the verge of death from wounds, exposure, exersion, & TB, Kobunji confesses his weakness to Jokichi. But -- looking as amiable & pitiful as any man can look -- he adds, "I feel like forgiving myself."

At that point Jokichi moves in, eager to kill this foolish, good-hearted assassin. But Kobunji falls dead, face-first into the snow, & the onlyk thing Jokichi can do is slash & slash & slash the dead body in outraged frustration.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

Chuji (played by Ryunosuke Minegishi in the previous film) doesn't even appear in Part III at all.

Chuji (played by Ryunosuke Minegishi in the previous film) doesn't even appear in Part III at all. That a tale marked by carnage is exploitation may be true, but there is yet something of the artfilm about Jokichi's simple straightforward action & adventure.

That a tale marked by carnage is exploitation may be true, but there is yet something of the artfilm about Jokichi's simple straightforward action & adventure. The characters aray is thrilling. This is not to say they are deeply portrayed, but they are hugely portrayed. The man with the patch in the first two episodes, & Windmill Kobunji in the third, are, like Jokichi himself, intense figures, impressing by the flick of a wanderer's cape, a quirk, or an expression.

The characters aray is thrilling. This is not to say they are deeply portrayed, but they are hugely portrayed. The man with the patch in the first two episodes, & Windmill Kobunji in the third, are, like Jokichi himself, intense figures, impressing by the flick of a wanderer's cape, a quirk, or an expression.

In fact, however, Jokichi is attracted to Kobunji's character & nature, & does become a meddler against his better judgement.

In fact, however, Jokichi is attracted to Kobunji's character & nature, & does become a meddler against his better judgement. It would seem he pities the terribly ill assassin, but what is more likely is that he felt challenged by Kobunji & would not let the assassin die until the two of them could have their own match.

It would seem he pities the terribly ill assassin, but what is more likely is that he felt challenged by Kobunji & would not let the assassin die until the two of them could have their own match. And when that encounter does finally happen, Jokichi deflects the assassin's flying blade.

And when that encounter does finally happen, Jokichi deflects the assassin's flying blade. The extended carnage, this amazing ballet of death, has at its core two men we have followed & on some level liked, so it has emotional impact as well as the beauty of its choreography.

The extended carnage, this amazing ballet of death, has at its core two men we have followed & on some level liked, so it has emotional impact as well as the beauty of its choreography.