Masaki Kobayashi's Cannes Festival award winning Kwaidan (Kaidan, Toho, 1964) consists of four short supernatural tales with historical settings, based on Lafcadio Hearn's versions of popular folktales. Besides the Jury Prize at Cannes, it also received the Kinema Junpo (Japanese Oscar) for the screenplay, & the Mainichi film award for art diretion & cinematography.

Masaki Kobayashi's Cannes Festival award winning Kwaidan (Kaidan, Toho, 1964) consists of four short supernatural tales with historical settings, based on Lafcadio Hearn's versions of popular folktales. Besides the Jury Prize at Cannes, it also received the Kinema Junpo (Japanese Oscar) for the screenplay, & the Mainichi film award for art diretion & cinematography.

Hearn was known as Koizumi Yakumo in Japan. He wrote these tales after his Japanese wife Setsu told them to him or translated them for him after she conducted interviews with peasant storytellers, as Hearn did not speak Japanese.

If he'd been fair about it, she'd at least be credited as co-writer. How much he changed these tales is hard to know; he is for example the ultimate authority for "The Snow Woman" though after his initial publication of the tale it became a standard in many additional retold versions.

Of the four tales, only the second, The Snow Woman (Yuki Onna) starring keiko Kishi in the title role & Tatsuya Nakadai as the man she spares from death, contains no martial arts aspect. The other three tales are quite clearly Sword & Sorcery, & constitute some of the best fantasy of any kind ever committed to celluoid.

Kobayashi said of his lyrical horror-fantasy film, "It's spiritual concerns are its heart. I am not satisfied that people call it a horror film." And indeed there is depth of all kinds in this anthology film, of spirit, of cinematic art, of acting.

For those of us who collect supernatural literature & are used to the idea that supernatural fiction can & should be about the spiritual life of humanity & not merely about the surface-subject of ghosts & gore, it's really no surprise that a film can be intelligent, spiritual, & still pretty much convey tales of terror & the supernatural.

With words like "masterpiece" thrown about for anything that is at least slightly better than commercial pablum, it's hard to know what to call a film of truly monumental achievement. It's one of a handful of films that has actually had lasting impact on my own life & art, having first seen it when young, & several times in the decades since, invariably enriched by the experience.

Just make sure you watch the 183 minute version, as there are versions out there with twenty minutes excised, & one cut down by almost forty minutes. The condensed versions lack critical scenes from "Hoichi the Earless" & the shortest version lacks the entirety of "The Woman in the Snow." And these are the two most important of the four tales.

For some viewers Kwaidan is too long to watch in one sitting, but it's four stories, so watch them in two sittings for crine out loud, because there's nothing that deserves truncating.

I. The Black Hair

The four tales rather loosely represent four seasons, beginning with autumn's The Black Hair (Kurokami).

The automatic sense that hair is frightening is a cultural button-pusher in Japan, but probably not until the American "J Horror" craze in the 1990s & introduction of such films as The Ring (Ringu, 1998) did it become a familiar idea in the west.

The tale is about a samurai (Rentaro Mikuni) who abandons his faithful loving first wife (Michiyo Aratama) in order to marry into a wealthy family to escape his poverty. His second wife (Misako Watanabe) brought him status, but nothing of love.

What he has gained cannot mend his feelings of guilt & error for having left a good wife to fend for herself without means. What he has gained cannot mend his feelings of guilt & error for having left a good wife to fend for herself without means.

He tries to lose himself in archery & equestrianism, but is constantly interrupted by images of his first wife & by the sound of her working at her spinning-wheel.

The spinning-wheel sound & imagery is emotionally complex, for on the one hand it is domestic art that fills the samurai's heart with nostalgia for his creative & industrious wife who he longs to see again.

But on the other hand ithe ghostliness of the spinning has intimations of a jusifiably vengeful woman casting spidery webs.

Finally he is compelled to return to his previous home. He finds the place in shambles, but his wife is still waiting in the one part of the house that she has managed to keep comfortable & clean. She puts aside her spinning to care for him lovingly.

For the first time in years he feels at ease, & knows he should never have left for material gain. But the next morning he discovers he has slept with a corpse, & the gorgeous hair of his dead wife becomes a hideous living thing intent on exacting vengeance against him.

II. The Woman in the Snow

The Woman in the Snow (Yukionna) is a fantasy of considerable depth, with visual elegance & unutterable weirdness.

Kobayashi selected an occasionally expressionistic, occasionally hyper-realistic tone for the piece that makes it seem as though the woodcutters in the forest have found their way to a "realm between" the real & the unreal.

The beautiful Keiko Kishi plays the deadly snow fairy, who finds the woodcutters asleep in a snow-shrouded hunter's shack. The door opens as of its own accord & she shuffles forth in her white kimono, bends down close to the face of the elderly woodcutter (Hamamura Jun), & breaths onto him so that he is frozen & dead.

Petrified from fear, but awake & seeing this horrific incident, the young woodcutter (Tatsuya Nakadai) gazes into the pallid face of death, his own large moist terrified eyes like pools of youthful beauty.

The snow fairy is about to breathe upon him but is smitten by his beauty. As she backs away, she warns him never to speak of what he has seen this night, or she will surely return & kill him after all.

In days of kinder weather, a sweet young woman is seen on a pilgrimage. She had intended to continue to some destination, but she meets the humble handsome woodcutter & they fall in love. She is the perfect wife & he is a happy, lucky man. They have three children as ten years of bliss come & go. In days of kinder weather, a sweet young woman is seen on a pilgrimage. She had intended to continue to some destination, but she meets the humble handsome woodcutter & they fall in love. She is the perfect wife & he is a happy, lucky man. They have three children as ten years of bliss come & go.

Then one cold night when their three children are abed, he sees the face of his wife Yuki in firelight weaving straw sandles for the children. The light makes her look pale as a ghost.

He is momentarily shocked, but then smiles at his own weird thought. She asks what bothered him, & he told her the tale of how he'd once had a terrible encounter with a snow fairy that looked a bit like her.

As he finishes his tale, Yukionna rises up from where Yuki had been seated, & reminds him she swore surely to kill him if he ever spoke of their encounter.

Nakadai will not require dialogue for his expressive eyes to convey the confusion, terror, & sadness that sweeps over him in waves as she tells him that it is only for the sake of their children will she spare his life. But he has broken the spell, & will never see her again. The door opens of its own accord, & she shuffles away in the manner of the snow spirit, her path snow-laden out of season.

III. Hoichi the Earless

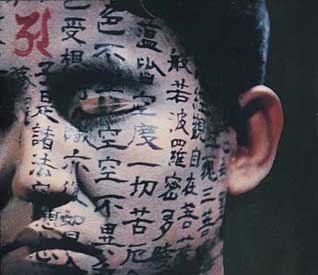

The best episode is the longest: Hoichi the Earless (Hoichi miminashi) starring Kasuo Nakamura as Hoichi the blind biwa player, Tetsura Tamba as the ghostly retainer of the infant emperor, & Takashi Shimura as the priest who sets out to save Hoichi from the ghosts of the Taira who died centuries before at Dan-no-ura.

Hoishi is a biwahoshi, of a sect of blind monk-minstrel who specialized in recitations of the Tales of the Taira Clan (Heike monogatari), the national epic of Japan, chronicaling the war between the Genji Clan & the Taira.

Hoichi is such a fine performer in reciting the poem & playing the stringed biwa that the ghosts of the Taira have become eager to hear him. A representative of the Taira arrives by night, claiming only that a wealthy lord is staying in a nearby mansion, & desires to hear his performance. Hoichi is such a fine performer in reciting the poem & playing the stringed biwa that the ghosts of the Taira have become eager to hear him. A representative of the Taira arrives by night, claiming only that a wealthy lord is staying in a nearby mansion, & desires to hear his performance.

Blind Hoichi does not realize that as he recites the epic through the night, the ghosts reenact their own history. Their heroic tragedy unrolls like a picture-scroll, some of the most beautiful images of medieval warfare ever caught on celluloid.

The priest is slow to realize that Hoichi is being taken away from temple compound night after night, & becoming increasingly ill as the days progress.

He is followed by an acolyte who reports back not that Hoichi was led by a wealthy family's retainer to a mansion, but went alone to a graveyard, & performed amidst gravestones. The priest now understands that when the epic is completely told, the Taira ghosts will tear him to pieces.

Since he is blind, Hoichi had never guessed the truth. The vulnerability of Hoichi & the efforts of the priest to save him from long-dead warriors makes for non-stop colorful suspense.

Sutras are written all over Hoichi's body to make him invisible to spirits. Only his ears have the priest & monks missed while writing the sacred text. When the Taira vassal arrives, he cannot find Hoichi, but sees only his ears floating in the place where Hoichi would ordinarily be seated.

IV. In a Cup of Tea

The most subtle of the four tales is In a Cup of Tea (Chawan no naka), starring Kanemon Nakamura as the spear-armed samurai & Nakaya Noboru as the smiling samurai ghost.

It shows the psychological transformation of an imperturbable samurai who is broken down into a crazed hysteric because he cannot permanently slay the supernatural retainers of a ghost whose soul he injested from a cup of tea.

The three retainers of the swallowed ghost come to our spearman for consecutive duels. Even though he wins these encounters with his yari-jutsu or spear art, it is clear he can never permanently slay that which is already dead.

Although there is no "wraparound" story like there is for most anthology films, it's interesting to note that In a Cup of Tea is narrated by an author (Takizawa Osamu) who is attempting to find an ending for a folktale he has heard in an incomplete form. This would imply that we've just seen stories from some classic book, as indeed we have.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|