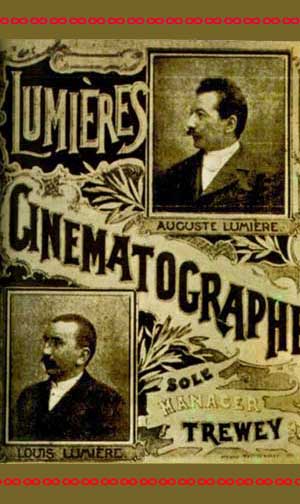

The Lumiere brothers Auguste (1862-1954) & Louis (1864-1948) were inventors who joined the big race to improve & make reliable motion picture cameras & projectors. With the name Lumiere, meaning "light," it's almost as though they were fated by some celestial birthright to follow the path they chose

The Lumiere brothers Auguste (1862-1954) & Louis (1864-1948) were inventors who joined the big race to improve & make reliable motion picture cameras & projectors. With the name Lumiere, meaning "light," it's almost as though they were fated by some celestial birthright to follow the path they chose

Their Cinematograph was an all-purpose camera that filmed, developed, & projected moving pictures all from the same box.

When it came to making the movies, Louis gets the lion's share of the business, though Auguste's contribution may well be underestimated. They had their first public exhibition of short-short films in 1895, & a year later went on tour to Asia Minor & America.

Their real interest was in invention rather than film production so it's surprising how many films Louis managed to make, by some estimates over one-thousand four-hundred.

The majority were just scenes of places, & the great leaps in content would in the main go to fellow French filmmaker Georges Milies, & to American filmmakers brought together by William K. L. Dickson who ran the Black Maria studio for Thomas Alva Edison.

The Lumieres did show considerable skill & imagination in filmmaking but they just never pushed it as far as others immediately felt they must do. This was probably because their highest creative juicies were committed to further inventions, among which would be sound equipment & color process cameras.

The Lumiere brothers belong even in the anals of early animation for their stopmotion trick film of a dancing skeleton, mounted on occasionally visible strings.

The Lumiere brothers belong even in the anals of early animation for their stopmotion trick film of a dancing skeleton, mounted on occasionally visible strings.

As The Skeleton of Joy (Le Squelette joyeux, 1897) leaps & bounds happily, parts of it drop off & reattach throughout the dance.

At one point the joyful skeleton collapses into a heap of bones & puts itself back together. It then hops about bouncing its severed head up & on its neck. All very antic & amusing!

The Lumieres had not at first thought of filmmaking as having a foremost value as entertainment but followed Etienne-Jules Marey's attitude that they were improving a scientific instrument. George Milies attempted to purchase their motion picture inventions to adapt for use in his vaudeville theater of magicians.

Melies clearly got them thinking in terms of public entertainments, & their excuses not to sell him such equipment may have been to slow down the competition. When the Lumiers began making movies hand over fist, most were just pastorals or films of place, as they lacked Melies' imagination.

But now & then as with The Skeleton of Joy they were trying to be as imaginative as Melies, falling short in that Melies would've added a magician (played by himself), a jest, or even a story context, whereas for the Lumieres, if they could make a skeleton dance, they'd done enough.

Vastly more typical of the Lumieres' films are such minute-films as Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (Arrivee d'un train a la Coitat, 1895), in which a train pulls into a snowy station.

Vastly more typical of the Lumieres' films are such minute-films as Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (Arrivee d'un train a la Coitat, 1895), in which a train pulls into a snowy station.

There's no story or context beyond the train station. We see women in hats & long dresses & men in work clothes, several carring bundles rather than suitcases, either meeting arrivals or preparing to board.

Arrival is the first benefactor of the oldest cinema-related urban folklore, as it was said many years after that the unsuspecting viewers the Lumieres invited to the premiere showing of their first ten films panicked when the train came at them.

As the story spread to other continents, it got transferred to other films, so that it was allegedly the Edison Company's Black Diamond Express (1896) that caused the public's panic. Ultimately any early film with a train heading toward the camera would get this piece of mythology hung on it.

Among those first publically exhibited films was Exiting the Factory (La Sortie des usines Lumiere, 1895) showing a great many women workers & a few men leaving work, flooding out the gate of the Lumieres' factory. Among those first publically exhibited films was Exiting the Factory (La Sortie des usines Lumiere, 1895) showing a great many women workers & a few men leaving work, flooding out the gate of the Lumieres' factory.

That day in 1895, five days after Christmas, when the Lumieres arranged their first exhibition of ten films, this one was said to have been shown first, & those gates have since become symbolic as the gate of cinema houses since the Lumieres had gotten thirty-some people to come to a teahouse for a show.

The audience hadn't been told what to expect, & at first saw only a stationary image projected into view, like any magic lantern exhibition. When the image began to move, the audience was stunned. By its age it has regained some appeal, & its interesting to see that women got dressed up so well just to to factory work. It kind of deserves it's position in film history as a classic.

There are far fewer men than women among the workers, but three of the guys are leaving the factory by bicycle. A large dog causes one chap to run out of its way, as though the dog might be dangerous.

It took a while for the Lumieres to figure out a film needed more than motion to sustain interest.

It took a while for the Lumieres to figure out a film needed more than motion to sustain interest.

At the beginning of the film age, people just lined up for what became known as "actuality films," for the pure novelty of seeing photographs of actual places & events spring to life.

The brothers & their dad expected the sudden rage for seeing pictures move would be a fad & well understood the novelty would wear off.

But rather than assuming the future of films was more sophisticated content, they thought the future of their inventions would be for the scientific study of motion, & eventually they'd be selling their equipment for use primarily in the sciences.

Additional "actuality films" include Carmaux: Drawing Out the Coke (Carmaux, defournage du coke, 1896), a factory scene of slag being removed from a giant furnace, French factory workers spraying it with water to cool it down & crumbles. Additional "actuality films" include Carmaux: Drawing Out the Coke (Carmaux, defournage du coke, 1896), a factory scene of slag being removed from a giant furnace, French factory workers spraying it with water to cool it down & crumbles.

One of the more interesting actualities captures a real event that occurred at the Lumiere factory.

Though minor in content, viisually Demolition of a Wall (Demolition d'un mur, 1896) is highly effective.

It's another brief one-shot scene showing laborers knocking down a thick old stone wall, using some kind of hand-cranked jack to push over, then mashing the pieces. The scene becomes clouded white with dust when the wall tumbles.

The Sea (Le Mer, 1895) shows four young men running out along a narrow dock & leaping feet-first into the shallow sea. They then rush ashore with the incoming waves, to repeat the act.

The Sea (Le Mer, 1895) shows four young men running out along a narrow dock & leaping feet-first into the shallow sea. They then rush ashore with the incoming waves, to repeat the act.

City streets as well as water would remain cliches of the actuality genre. Cordeliers' Square in Lyon (La Place des cordeliers a Lyon, 1895) shows a street in Lyon, France, of three-story buildings, awninged businesses at street level, pedestrians, & horse-drawn vehicles including trolly.

Another three-quarters of a minute for the actualities genre is The Photographic Congress Arrives in Lyon (Neuville-sur-Saone: Le DÈbarquement du congres de photographie a Lyon, 1895).

It shows well-dressed men & women disembarking from a riverboat, providing quite a display of business travel fashion of the era. It shows well-dressed men & women disembarking from a riverboat, providing quite a display of business travel fashion of the era.

The majority of the guys are wearing flat straw hats & those who spot the cameraman tip their hats as they hurry by.

The hat-tipper with largest flourish, who passes last, is carrying a camera & tripod. He is P.J.C. Janssen, a well known astronomer who with Norman Lockyer discovered & named the element helium.

By the title we know that these people are members of the Photographic Congress, a famous gathering in the history of early cinema which occured a Neuville-sur-Saone.

Louis Lumier shot the film in the morning upon the riverboat's arrival, & he exhibited it that same afternoon to the photographic congress. It's often said to be the first French actuality film to commemorate a specific event.

Actualities featuring infants was an easy subject to hold people's interest. Baby's Meal (Repas de bebe, 1895) provides a pleasant family scene, husband & wife with their baby, outdoors at a garden table.

Actualities featuring infants was an easy subject to hold people's interest. Baby's Meal (Repas de bebe, 1895) provides a pleasant family scene, husband & wife with their baby, outdoors at a garden table.

The father (Auguste Lumiere himself) feeding the infant girl (Andree Lumiere) in a highchair, as the mom (Marguerite Lumiere) has her tea.

Fishing for Goldfish (La Peche aux poissons rouges, 1895) shows a father holding a white-clad baby in a standing position beside a fishbowl. The child tries to catch the goldfish. The infant also looks straight into the camera with some curiosity.

There appears to be some question as to whether Louis Lumiere actually filmed Babies Quarrel; aka, Childish Quarrel (1896), athough the Lumiere company distributed it. There appears to be some question as to whether Louis Lumiere actually filmed Babies Quarrel; aka, Childish Quarrel (1896), athough the Lumiere company distributed it.

Two babies seated side-by-side in highchairs are wearing big fluffy bonnets. One has a cup on the highchair tray, the other a toy lamb.

At three-quarters of a minute you wouldn't expect to see so much in a film of this nature. Yet the two babies just exude their own unique personalities. The child with the lamb wants the cup so starts wacking on the unagressive kid, who bursts into tears.

Obviously the babies could not take direction & could not have their actions scripted. The photographer had to have faith they'd do something babyish before the short bit of film ran out, & faith paid off.

Comic skits were soon popular with the public. Although comedy was not Louis Lumiere's strongest talent, the attempts at humor always have something interesting about them. Comic skits were soon popular with the public. Although comedy was not Louis Lumiere's strongest talent, the attempts at humor always have something interesting about them.

The gardener in The Waterer Watered; aka, The Sprinkler Sprinked; or, The Tables Turned on the Gardener (L'Arroseur arrose, 1895) waters his flower garden from a hose.

In a prank as old as garden hoses, a lad sneaks up behind & stands on the hose, stopping the flow. The gardener looks in the end of the hose, & the prankster behind him lifts his foot. The wet gardener takes off running to catch the young man, giving him a playful spanking before getting back to the garden.

The Waterer Watered is generally considered the first "plotted" film made in France. Georges Melies did a remake called Watering the Flowers (L'Arrouseur, 1896) but no copy is known to survive.

Another film that amuses is Horse Trick Rider (La Voltige, 1895). The scene has a groom holding a horse's reins while a second chap helps the rider who is trying to get on the bareback steed.

Another film that amuses is Horse Trick Rider (La Voltige, 1895). The scene has a groom holding a horse's reins while a second chap helps the rider who is trying to get on the bareback steed.

The would-be rider keeps falling off repeatedly as the groom laughs. For conclusion he manages not to fall off the horse, but neither can he get it to move.

It looks like the same "stunt man" in Jumping Onto the Blanket (Le Saut a la couverture, 1895) depicting a failed blanket-toss.

Four men are holding the corners of a blanket. The fifth man wants to get in the blanket to be tossed up & down. He takes multiple runs trying to jump on, with a sixth man to help him flip over to land in the blanket on his back. Four men are holding the corners of a blanket. The fifth man wants to get in the blanket to be tossed up & down. He takes multiple runs trying to jump on, with a sixth man to help him flip over to land in the blanket on his back.

He keeps missing & landing on the ground, being absurdly clumsy. Even when he almost makes it, he slips off it onto the ground. For climax he actually manages to stay in the blanket, & the four men raise him up & down rather weakly.

Both "clumsiness" films feature a fellow in white shirt & pants & a flat-topped hat, as though the Lumieres were about to stumble into the idea of a "series character."

The performer reaches a perfect level of over-acting, too exaggerated to be viewed as an "actuality" of someone honestly that awkward, but pure slapstick comedy. And it's fascinating to see intimations of great slapstick clowns to come in this anonymous performer's antic motion.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

Additional "actuality films" include Carmaux: Drawing Out the Coke (Carmaux, defournage du coke, 1896), a factory scene of slag being removed from a giant furnace, French factory workers spraying it with water to cool it down & crumbles.

Additional "actuality films" include Carmaux: Drawing Out the Coke (Carmaux, defournage du coke, 1896), a factory scene of slag being removed from a giant furnace, French factory workers spraying it with water to cool it down & crumbles.

It shows well-dressed men & women disembarking from a riverboat, providing quite a display of business travel fashion of the era.

It shows well-dressed men & women disembarking from a riverboat, providing quite a display of business travel fashion of the era.

There appears to be some question as to whether Louis Lumiere actually filmed Babies Quarrel; aka, Childish Quarrel (1896), athough the Lumiere company distributed it.

There appears to be some question as to whether Louis Lumiere actually filmed Babies Quarrel; aka, Childish Quarrel (1896), athough the Lumiere company distributed it.

Four men are holding the corners of a blanket. The fifth man wants to get in the blanket to be tossed up & down. He takes multiple runs trying to jump on, with a sixth man to help him flip over to land in the blanket on his back.

Four men are holding the corners of a blanket. The fifth man wants to get in the blanket to be tossed up & down. He takes multiple runs trying to jump on, with a sixth man to help him flip over to land in the blanket on his back.