The historical Mito Komon aka Tokugawa Mitsukuni (1628-1700) was the grandson of shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu. The historical Mito Komon aka Tokugawa Mitsukuni (1628-1700) was the grandson of shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu.

In pulp fiction, comics, anime, cinema from the silent era on, & in a classic television series, Mito wandered Japan righting injustices. Historically he was the second daimyo or lord of Mito Province, & in real life became a scholarly recluse.

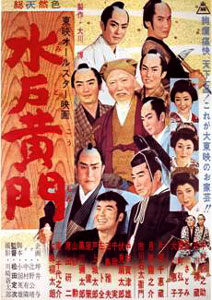

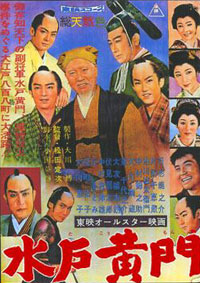

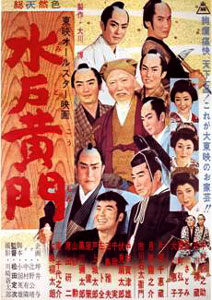

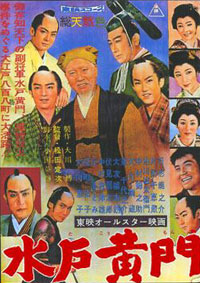

Several films feature this character, beginning early in the silent era. A color, widescreen version, Mito Komon (Lord Mito: The All Star Version,1960) was produced by Hiroshi Okawa & directed by Teiji Matsuda aka Sadaji Matsuda or Sadatsugu Matsuda, son of silent film pioneer director Shozo Matsuda.

The story hasn't the slightest interest in historical facts & just runs off in its own direction. This is regarded as the third in a series, with an overlapping central cast from two earlier films starring Ryunosuke Tsukigata as Lord Mito, though each film stands alone. The story hasn't the slightest interest in historical facts & just runs off in its own direction. This is regarded as the third in a series, with an overlapping central cast from two earlier films starring Ryunosuke Tsukigata as Lord Mito, though each film stands alone.

Mito Komon is played in the white-whiskers make-up traditional for the character. This episode of his biography assumes there were two Mitos, a younger who was the son of the elder.

The young Mito is living as a happy-go-lucky townsman. He's played by the physically beautiful Hashizo Okawa, who before becoming a film star played female roles in the kabuki theater.

Hashizo is not well known in the west, though his film series about Shingo Aoi the bastard son of a shogun have some cache among samurai film fans world-wide, being more easily accessible as subtitled imports than are most of Hashizo's films.

Many of his films, however, have in recent years become available with subtitles, but only on the "grey" or "brown" market. Official releases are not subtitled. Many of his films, however, have in recent years become available with subtitles, but only on the "grey" or "brown" market. Official releases are not subtitled.

The elder Mito is accompanied by his vagabound friends & companions Kaku & Suke (Chioyosuke Azuma & Satomi Oka).

Arrayed around the younger Mito are a number of interesting young men. Kinnosuke Nakamura (later Yorozuya) plays a chief of firemen. He's a tattooed ruffian, sweet natured & loud, which is the typical manner by which firemen were played.

Another handsome young star, Kazuo Nakamura (Kinnosuke's real-life brother) plays a detective. Also in the cast is Cheizo Kataoka, a great star from the silent film era, playing the retired emperor's minister.

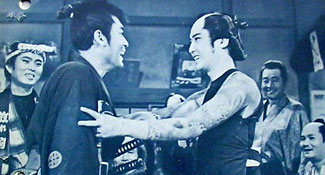

Ryutaro Otomo, maturing but still very, very handsome, plays a rather cute ronin with a very close a relationship with Kinnosuke's tattooed fireman character. Ryutaro Otomo, maturing but still very, very handsome, plays a rather cute ronin with a very close a relationship with Kinnosuke's tattooed fireman character.

The story strongly implies they are lovers, & one of the firemen noting jealousy says point-blank, "People will think you lost your girl."

This is a "samurai detective" tale centering around fires that occured in 1691 in several towns near Kyoto, & eventually in Kyoto itself.

One of the highest crimes was arson, since a crowded town or city was made of wood with paper windows. The toughest of tough guys were frequently firemen, famous for their tattoos such as would in a much later era be associated with yakuza. There's a deadly arsonist abroad who must be stopped, & on this premise hangs a lot of humor, some effective drama, & plenty of action.

Hashizo Okawa was an enormous star in his day but very few of his films were seen outside of Japan. Hashizo Okawa was an enormous star in his day but very few of his films were seen outside of Japan.

Surprisingly enough most of his films were provided with subtitled prints that have circulated in the United States & Canada chiefly in ethnic theaters until the video era shut down nearly all of those, or some few shown by the Japan Society in New York City.

Oshobu (The Great Challenge, Toei, 1965) was directed by Umetsugu Inoue, a B-director for Toei who pumped out a lot of minor chambara & yakuza films, with a side-specialty in lighthearted musicals to set him a bit apart. The old subtitled 35 mm print which I saw credited the film to Umeji Inoue, a very common mistranslation that has found its way even into reference books.

Curiously, Inoue also worked in Hong Kong directing for Shaw Brothers Studio, a rarity of the same director doing both judai-geki & wuxia. Though a hardworking committed director, he never broke out from the masses of B directors. Curiously, Inoue also worked in Hong Kong directing for Shaw Brothers Studio, a rarity of the same director doing both judai-geki & wuxia. Though a hardworking committed director, he never broke out from the masses of B directors.

Oshobu starred Hashizo Okawa opposite Chiezo Kataoka. Set about 1810, the Tokugawa government tries to get truncheons (which serve as police badges) away from certain magistrates who've become gangsters severely abusing their authority.

It's a light comedy, but with violent, well choreographed fights. Hashizo & Chiezo are extremely charming together.

Another film I recall imperfectly from a theater viewing as a great deal of fun was Baraketsu Shobu (Three Young Rebels, Toei, 1967), directed by Sadaji Matsuda aka Teiji Matsuda.

Takashi Shimura (best known for his lead role in Seven Samurai) played a Meiji era detective. Hashizo Okawa plays his wayward son. Supporting stars included Junko Fuji, Shingo Yamashiro, Naoko Kubo & Minoki Ryuhei.

As with many but by no means all of Hashizo's films, there is a sense of Three Young Rebels being a "family film" most suitable to kids or teens. It was very common to star him opposite someone much older like Takashi Shimura, perhaps to keep the adults interested on family theater outings. In his 1950s films he was commonly the second-lead opposite Ryotaro Otomo, & in the early 1960s he was the youth-star opposite the mature Chiezo Kataoka.

Both Otomo & Kataoka had been matinee idols before the war but were being displaced by younger stars like Hiroki Matsukata, Kinnosuke Nakamura, & Hashizo Okawa.

Hashizo has the title role in Irezumi Hantaro (Tattooed Hantaro, 1963) is directed by another chambara pioneer who started in the silent era, Masahiro Makino. Hashizo has the title role in Irezumi Hantaro (Tattooed Hantaro, 1963) is directed by another chambara pioneer who started in the silent era, Masahiro Makino.

Hantaro starts out as a harmless pantywaist who loses ten ryu gambling & is forced to flee his home, abandoning his elderly mother. Three years later, he has become a jaded gambler.

The swordplay is nicely choreographed in sloppy styles to suggest the lesser training a gambler might obtain, rather than the poised perfection of a samurai who has trained from childhood. Within that boundary, Hantaro is a good fighter.

Although the story is framed like a rough-&-tumble swordplay film, it is actually a serious drama with only a little swordplay at the beginning & end. The bulk of the film regards the story of Hantaro's love affair with a woman sold into prostitution. They run away together even knowing they will be pursued by gangsters, & despite that she is too ill for the two of them to have any chance of starting a new life together even supposing they could manage to escape.

Heavy with melodrama, it's an overwhelmingly sad costume play, classier & less fun than the bulk of Hashizo Okawa's starring vehicles of the early 60s. He seems a little overweight in the role, or else his usual girlish beauty is purposely marred by makeup so that his extreme good looks won't undermine the tragic nature of the tale. Heavy with melodrama, it's an overwhelmingly sad costume play, classier & less fun than the bulk of Hashizo Okawa's starring vehicles of the early 60s. He seems a little overweight in the role, or else his usual girlish beauty is purposely marred by makeup so that his extreme good looks won't undermine the tragic nature of the tale.

Hashizo gets to reveal his singing talents, performing a lovely folksong for a peasant audience, accompanied by his girlfriend on samisen. Such moments of beauty, against the gorgeous (if familiar) sets of the Toei movie town, help to underscore the extremes of feudal Japan: the appreciation of beauty by all classes high & low, & the easiness of violence.

The "tattoo" of the title is different than might be expected. Tattooed gamblers are a staple of the genre, but Hantaro doesn't really have one of those imposing full body tattoos. At a critical moment in the drama, Hantaro decides on having the dying woman's name tattooed onto his arm in order to remember her forever, & so he can consider her as having been truly his wife despite any social stigma.

There are attempts at subtlty, as in the heroine's character never smiling during the whole film until she is dead of her illness; only then is there a smile upon her lips. For a costume tragedy, which tend to milk every twist of pathos for as many tears as possible, this is about as underplayed as such films ever get.

Hashizo was of a kabuki theater family, & this film has its root in an early 20th Century kabuki theater piece Irezumi Chohan, by Shin Hasegawa, who delighted in writing about society's riffraf & discarded. It is still performed by kabuki players or by bunraku puppets.

It was previously filmed in 1933 by Mansaku Itami a leading chambara director & father of Juzo Itami the yakuza-eiga director. For the remake, Masahiro Makino, a veteran chambara director of considerable stature, was clearly striving for more than an instant B-picture. To large extent, he succeeded.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

The story hasn't the slightest interest in historical facts & just runs off in its own direction. This is regarded as the third in a series, with an overlapping central cast from two earlier films starring Ryunosuke Tsukigata as Lord Mito, though each film stands alone.

The story hasn't the slightest interest in historical facts & just runs off in its own direction. This is regarded as the third in a series, with an overlapping central cast from two earlier films starring Ryunosuke Tsukigata as Lord Mito, though each film stands alone. Many of his films, however, have in recent years become available with subtitles, but only on the "grey" or "brown" market. Official releases are not subtitled.

Many of his films, however, have in recent years become available with subtitles, but only on the "grey" or "brown" market. Official releases are not subtitled. Ryutaro Otomo, maturing but still very, very handsome, plays a rather cute ronin with a very close a relationship with Kinnosuke's tattooed fireman character.

Ryutaro Otomo, maturing but still very, very handsome, plays a rather cute ronin with a very close a relationship with Kinnosuke's tattooed fireman character.

Curiously, Inoue also worked in Hong Kong directing for Shaw Brothers Studio, a rarity of the same director doing both judai-geki & wuxia. Though a hardworking committed director, he never broke out from the masses of B directors.

Curiously, Inoue also worked in Hong Kong directing for Shaw Brothers Studio, a rarity of the same director doing both judai-geki & wuxia. Though a hardworking committed director, he never broke out from the masses of B directors.

Heavy with melodrama, it's an overwhelmingly sad costume play, classier & less fun than the bulk of Hashizo Okawa's starring vehicles of the early 60s. He seems a little overweight in the role, or else his usual girlish beauty is purposely marred by makeup so that his extreme good looks won't undermine the tragic nature of the tale.

Heavy with melodrama, it's an overwhelmingly sad costume play, classier & less fun than the bulk of Hashizo Okawa's starring vehicles of the early 60s. He seems a little overweight in the role, or else his usual girlish beauty is purposely marred by makeup so that his extreme good looks won't undermine the tragic nature of the tale.