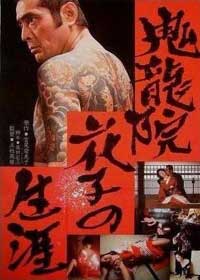

Set from 1918 to the 1940s, the titular figure of Onimasa (Toei, 1982) provides a character study of family life for an egomaniacal oyabun or gangster boss of the town of Shikoku.

We view Onimasa & his wife mainly through the eyes of the adopted daughter Matsue (Masako Natsume). As a child she was scared & sad leaving home, not understanding what the future holds, & her new life with Uta & Onimasa is never to be quite normal, though she certainly does adapt to it. We view Onimasa & his wife mainly through the eyes of the adopted daughter Matsue (Masako Natsume). As a child she was scared & sad leaving home, not understanding what the future holds, & her new life with Uta & Onimasa is never to be quite normal, though she certainly does adapt to it.

Hideo Gosha is an often overrated director but now & then he lives up to his reputation, & this is an effective film with definite merit. When first released, the film was a great commercial success in Japan, besides making a circuit of international film festivals. Among young viewers Matsue was the favorite character. Her winning line, "I am the daughter of the great Onimasa! Don't shit with me!" became a teen catch phrase of the time.

Tatsuya Nakadai plays Onimasa very broadly; he tips his hat to the Bogart machismo simultaneously in fun & with realism. During a cruel sporting event (dog fighting), the losing mastiff's owner murders the winning dog. Onimasa agrees to help avenge the dog. The seriousness of this set-up not inhibited by the fact that it is also satiric.

Even though it's over a dog, the story becomes sweepingly heroic when Onimasa chooses justice over obeisance to a higher yakuza authority (Tetsura Tamba as the dignified, influential, but corrupt boss of bosses). But this is a tragic world wherein even heroism seems to serve no good, valid, or lasting purpose.

When Onimasa announces he will "Cease to be a dog," this kind of declaration would in many films lead to rebellious deeds in defense of honor, justice, or the meak. In the present case it reveals only that Onimasa's naivete is of a sort that genuinely believes in the myth of the yakuza as chivalrous commoner & last bastion of samurai ethos. One could almost wonder how he survived into middle age given his degree of naivete.

His refusal to cave in to corruption is no prelude to justice, but one more step toward his own inevitable downfall; his loss of connection to the upper echelons of gangsterdom; no heir to his yakuza family; ultimately, death in prison with every dream unrealized, except for his meaningless revenge on the rival oyabun who had years before assassinated a champion fighting mastiff.

As in many yakuza films there's a "final raid," an extended sequence of carnage. This raid is ironically devoid of meaning because Onimasa's younger daughter (Kaori Tagasugi) wanted to be where she was kidnapped.

The ironies play wholly off the yakuza-eiga of the 1960s which made certain assumptions about chivalrous yakuza, romantically played heros who really can succeed at achieving something of justice through mass slaughter. Onimasa likewise succeeds on the level of the superhuman's one-against-all raid, just as happens in the 1960s counterparts, killing the villains one by one while personally surviving horendous wounds. But given that his mission was to die with his foolish, kidnapped daughter who was so happy with her kidnapping, his successful raid meant nothing. The "great man" could not even pursue heroic death with success.

It's no wonder this film got nowhere as the official Japanese entry for the Academy Award, Best Foreign Film. It was naive of the producers to think it had a chance. Predicated as it is on the idea of twisting genre conventions of the previous decade, much of it would be almost incomprehensible to a western audience unfamiliar with the context, & who would see each excessive swagger as an unintentional joke rather than a brilliant commentary. Onimasa's endeavors seem, to anyone not familiar with the genre, not meaningless in context with his beliefs & dreams & his devotion to an unusual ethical code, but merely meaningless. To viewers long initiated in yakuza-eiga, of course, it makes a great deal more sense than that, but we're not members of the Academy.

Gosha's earlier yakuza epic Wolves is a better film than Onimasa for pacing & emotional impact. Onimasa is, even on its own merits, neither better nor worse than the classic ninkyo chivalry gangster films of the 1960s, though it does deserve a retroactive position among the best of those, a fine fine film even though already old-fashioned when it was released.

For some, however, at two & a half hours length, it may well wane thin with its repeated inclusion of "pinku" or softporn suggestiveness & the long patches of film-time without action. In the classic ninkya eiga, the veiwer is involved with the manners & ceremonies of gangsters for an hour or so, then there is a pay-off of shocking swordplay. Onimasa makes the viewer watch two or so hours of ceremony & (superior at least) character interaction with the violent pay-off awfully long in coming.

The violent climax fails to rise above the merely cathartic & ultimately exploitative conclusions of its 1960s equivalents. Truth be told, an aging Nakadai is far less convincing as the super-swordsman than was a young Ken Takakakura in his final-real one-against-all battles.

Female characterization excells the average from the yakuza-eiga glory-days (the unexcelled Red Peony Gambler not withstanding). The daughters & the two mistresses (Emi Shindo & Akiko Nakamura) are all convincing figures. And in particular, Onimasa's wife Uta is portrayed with dignity, subtle cruelty, & pathos, providing Shima Iwashita the opportunity of another in her long string of superb performances.

Introduced as the ultimate tough girl, mean-spirited with a vicious streak, Uta slowly achieves audience sympathy as we see deeper & deeper into her pose & come to understand her loneliness & devotion to Onimasa, keeping her true feelings hidden. Her death by typhus is a ferocious episode of the film. Shaking wretchedly, trying to put on make-up & play her shamisen, carressing the tattoo on her thigh which is the duplicate of her faithless husband's body tattoo, & finally confessing to her foster daughter, "I was mean to you, but not because I didn't like you."

And then Onimasa, realizing too late his need of this strong woman's presence, is too fearful of the typhus to even tell her his sentiment before she's gone. With her passing, Onimasa's downfall seems already complete. The rest of the film shows his spiritual heroism floundering. He loses his gruff, loud, posturing, swaggering self-certainty & only realizes at the end how his egomania kept him from enjoying the things that mattered: love of a family which deserved better than a gangster boss delivered.

The overall intent of the film is noble, but in execution, the yakuza-eiga fan can only remark on how the 60s films, almost by accident, achieved equal heights of humanity-despite-violence. Onimasa could not exist without the yakuza-eiga of the 1960s which it comments upon but, visually at least, imitates too slavishly, taking an hour too long to deliver the same punch-line. Yet this criticism applies mainly to the film's originality (or lack thereof) being intentionally an imitation of formerly popular genre. With a little patience for its pacing, Onimasa will provide the same rewards as the very best ninkyo-eiga of the mid & late '60s.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

We view Onimasa & his wife mainly through the eyes of the adopted daughter Matsue (Masako Natsume). As a child she was scared & sad leaving home, not understanding what the future holds, & her new life with Uta & Onimasa is never to be quite normal, though she certainly does adapt to it.

We view Onimasa & his wife mainly through the eyes of the adopted daughter Matsue (Masako Natsume). As a child she was scared & sad leaving home, not understanding what the future holds, & her new life with Uta & Onimasa is never to be quite normal, though she certainly does adapt to it.