Pale Flower vs Chivalry in Classical Yakuza Films

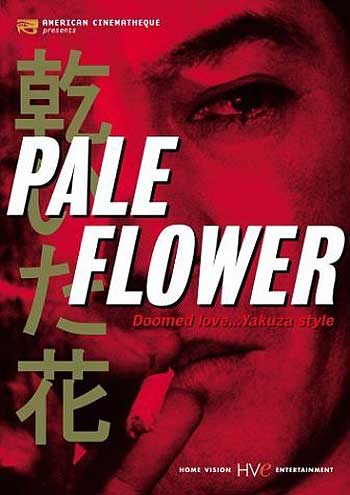

Masahiro Shinoda has claimed that his 1961 film Pale Flower (Kawaita hana, Shochiku, 1963) became the model of the crystallized yakuza-eiga or gangster films which Toei studios mimicked exhaustively. Masahiro Shinoda has claimed that his 1961 film Pale Flower (Kawaita hana, Shochiku, 1963) became the model of the crystallized yakuza-eiga or gangster films which Toei studios mimicked exhaustively.

Kon Ichikawa's Shanshiro of Ginza aka A Ginza Veteran (Ginza Sanshiro, Shin Toho, 1950) made 13 years sooner, plus a host of Toei films from the late 1950s rather puts a dent in Shinoda's claim of inventing the genre.

Yet his film may have presaged a new kind of film for Japan, even though it is not the specific sort of yakuza-eiga which Toei perfected about the same time as Pale Flower was released. Shinoda's film has more in common with cynical American film noir or French cinema verite rather than the chivalrous gamblers who dominated yakuza films for the rest of the decade.

One of the early successes that perfected the classical ninkyo or chivalrous formula was The Gambler aka Man to Man (Bakuto, Toei, 1964) directed by Shigehiro Ozawa (a poster for this film is shown here at the right). Koji Tsuruta plays Tsaburo Tachibana a chivalrous tattooed gambler of the Meiji era. Junko Fuji co-stars in an early role that gave her too little to do. One of the early successes that perfected the classical ninkyo or chivalrous formula was The Gambler aka Man to Man (Bakuto, Toei, 1964) directed by Shigehiro Ozawa (a poster for this film is shown here at the right). Koji Tsuruta plays Tsaburo Tachibana a chivalrous tattooed gambler of the Meiji era. Junko Fuji co-stars in an early role that gave her too little to do.

In the tale, a young dandified yakuza boss wishes to enter politics. He makes a deal with an Osaka train company resulting in a lot of poor people having their homes torn down. When the film's last reel rolls around, it's time for indignation to triumph as Koji Tsuruta's long-suffering character takes on all bad guys all at once.

Tachibana takes several direct hits with bullets bloodying his bared full body tattoo, but nothing can stop his longsword action, with graceless gory slaughter on all sides. In the end, his raid successful, he crawls away like a wounded animal, whether to live or die we are left to wonder.

Though it plays "good versus evil" with the chivalrous gambler standing for Good, Bakuto actually has fear of loss & change at its core, with the chivalrous gambler standing for old traditions in a world that is rapidly changing -- & rapid change was the hallmark of Meiji. Supporting cast in this minor classic includes Kotaro Satomi, Hiroki Matsukata, Yoko Minamida, Haruo Tanaka & Ryunosuke Tsukigata.

But as for the formative Pale Flower, Shinoda's film sets out to examine the aesthetic & ceremonial nature of the gambler's world, as Shinoda perceived it after interviews with police officers & visits to gambling dens.

We see the stylized manner in which they gamble, relate to each other, obey the paternal oyabun (boss or godfather), accept the organization as their only true family, & commit acts of violence (with or without regard for justice) because the gambler's duty is to his boss whose will cannot be questioned.

The choice of actors, costuming, pacing, setting, subject matter, & overall tone recurs in the following decade's worth of yakuza-eiga, amounting to no less than two films a month from Toei alone, & as many as a hundred films per peak year.

Shinoda's sexual obsessions in this & many of his films are masochistic, a trait common in later yakuza films as well. It is the rule that heroic yakuza bear emotional anguish for as long as possible, & sometimes physical anguish as well. In Brawl at Cape Shiretoko aka Storm on Cape Shiretoko aka Inviting the Storm to Shiretoko Key (Shin abashiri bangaichi: Arashi-o yobu shiretoko misaki, Toei, 1971) from the New Abashira Prison series, Ken Takakura as Katsuji Suehiro proves his manliness by grabbing hold of a red hot branding iron & looking soulful while his fingers smoke & sizzle.

The removal of part of the little finger as an apology is a recurrent act of masochistic obeisance in yakuza films. Shinoda originally shot the finger-cutting scene for Pale Flower so graphically that the studio censored it; as the film exists now, we're only shown the little box that holds the finger, after the deed is done. Later, studios would become jaded to this act of self-amputation, & film-goers would watch it in film after film.

Many yakuza films have little or no action until the final reel when an all-out-violent climax can be quite protracted, so what holds the viewers interest for the bulk of these films are variants in the minute details of ritual, from the oath taken upon joining a yakuza gang to methods of greeting to the apologetic finger-cutting. A novice viewer may not find these things interesting, but the more yakuza films one sees, the more intriguing the artifice of the ritualistic content of the film becomes; they become increasingly fascinating & telegraph increasing amounts of information about character responses to such artifice.

Upper body tattoos are additional proof of a hero's dedication to pain. The ultimate act of masochistic heroism is usually in the climactic battle wherein no injury is sufficient to stop our hero's mission. Upper body tattoos are additional proof of a hero's dedication to pain. The ultimate act of masochistic heroism is usually in the climactic battle wherein no injury is sufficient to stop our hero's mission.

The hero(es) take scores of wounds of the sort that would have long ago killed villains (for villains don't like pain), battling on & on, sometimes surviving as in Blood Will Tell (Furui yatsude gozansu: Kizudarake no jinsei, Toei, 1971) when the combined strength of gangsters & corrupt military officials is insufficient to stop a true hero.

Elsetimes the hero dies in the good fight, as happens when it is chivalrous yakuza (Koji Tsuruta) vs evil military officials in Presidential Gambling (Bakuchi-uchi: Socho Tobaku, Toei, 1968), from the Bakuchi-uchi "Gambling House" series.

The poster for this fourth episode is shown here at the left, with a still from this film immediately below, showing Junko Fuji & Tomisaburo Wakayama at graveside. (For an additional discussion of early ninkyo-eiga chivalrous gambler films, see Homoeroticism in Chivalrous Gambler Films with special reference to the Showa Zankyoden series).

Joan Mellon in The Waves at Genji's Door: Japan Through Its Cinema (New York: Pantheon, 1976) argues for the preeminence of symbolism in a film like Presidential Gambling, with the good oyabun standing in for moral, culturally isolationist & traditional values for all Japan, & the bad oyabun a usurper of tradition, like General Tojo seeking imperialist expansion throughout Asia. Mellon argues that identification with chivalrous gamblers liberated the Japanese population as a whole from guilt or blame for any part of World War II, laying the blame at the door of a few bad apples.

I'm not so convinced this sort of scapegoating is at all the subliminal message that helped make ninkyo or chivalrous yakuza such a popular idea in cinema through the 1960s. Casting the 1930s military establishment as the bad guys had as much to do with the public's justified anger that made "comfort women" of Japanese girls & told boys still on the child's side of manhood to crash their airplanes into the sides of ships. I'm not so convinced this sort of scapegoating is at all the subliminal message that helped make ninkyo or chivalrous yakuza such a popular idea in cinema through the 1960s. Casting the 1930s military establishment as the bad guys had as much to do with the public's justified anger that made "comfort women" of Japanese girls & told boys still on the child's side of manhood to crash their airplanes into the sides of ships.

No scapegoating is required to think ill of such things. If there is WWII symbolism in the fact that by the end of Presidental Gambling every good guy lies dead, it reflects on every Japanese family who lost so many who were loved.

I rather suspect that with the "death of God" when the Emperor himself informed the public that he was not a divine being, & therefore the Japanese not a divine race, it was easy to glom onto a romanticized version of a ritualized yakuza society that resembled feudalism at its imaginary finest, a place naive & safe & dreamily familiar. Not a utopian dream because it was a place of conflict & violence, but it was also a place where moral choices could be made by the sufficiently heroic, & if there was no god, there was still at least duty (loyalty) & compassion (humanity) by which to measure one's outer world & internal spirit.

Not all the conventional ingredients were set in place by 1963's Pale Flower. We do see a couple of yakuza tattoos among gamblers playing with their shirts off, but we don't know that Murakami or any other important character is tattooed, even though the tattooed ruffian hero had been de rigeur since kabuki plays of gamblers of the Tokugawa era. Not all the conventional ingredients were set in place by 1963's Pale Flower. We do see a couple of yakuza tattoos among gamblers playing with their shirts off, but we don't know that Murakami or any other important character is tattooed, even though the tattooed ruffian hero had been de rigeur since kabuki plays of gamblers of the Tokugawa era.

Shinoda's film in particular lacks the "chivalrous" ingredient that would inform the genre during most of its "classical" period from approximately 1964 to the very early 70s. If he'd made his film a decade later it would've seemed almost an anti-yakuza film reactionary in its refusal to romanticize. In Pale Flower, Ryo Ikebe as Murakami is fixated on a mysterious woman gambler Saeko (Mariko Kaga), though his physical relationship is with someone else.

It is to a great extent his fixation on this mysterious woman that induces his violent actions for his oyabun, not his devotion to his duty to the oyabun. The woman is a thrill-seeker & Murakami fears losing her to her interest in the ghostly drug-addicted Yoh, a character she knows to be appalling but even high-stakes gambling has become boring & she needs to push herself into new arenas, possibly even drug use. He puts off the final violent assault his oyabun has commissioned, because he wants the girl to witness him in bloody action, the ultimate thrill.

He derives personal release, an actual happiness, in killing. Later yakuza heros of the classic period do not express joy in killing, but have an edge of gentleness that renders them sorry for murderous actions that must be taken for the sake of one's sense of justice or humanity. He derives personal release, an actual happiness, in killing. Later yakuza heros of the classic period do not express joy in killing, but have an edge of gentleness that renders them sorry for murderous actions that must be taken for the sake of one's sense of justice or humanity.

They are conflicted about their duty to an oyabun who is apt to have a cruel agenda vs their sense of fair play or humanity which requires the gambler to remain in the shadows & not hinder or injure innocent folks from outside the gambler's world. By the mid-1970s when the chivalrous yakuza films had run their course, & more so with each decade, central protagonists of yakuza films were less heroic & increasingly sociopathic, so perhaps truer to Shinoda's original vision.

In the films which imitate Pale Flower but did add the chivalrous ingredient, obligation to the paternal boss vs a sense of fairness that when imbalanced leads to a thirst for revenge or justice are the major character motivations, themes opposing Pale Flower's grimmer sentiments.

Kon Ichikawa has the titular hero of Sanshiro of Ginza played by Susumu Fujita masochistically suffer everything, breaking his oath (hence his obligation) to a gangster only when the woman Sanshiro loves is threatened. Sanshiro does nothing to help himself, but turns his sixth-rank judo expertise against the yakuza gang because of the threat against an innocent. Sanshiro is not actually a yakuza; he's a physician; he does not necessarily live by any gambler's code. Yet in this 1950 film more than in Pale Flower we can see the root of the "duty vs humanity" motivations that predominated in the classic era of yakuza-eiga, though the torn figure is a doctor rather than a gangster.

Comparisons aside, Pale Flower is a stand-out film whether viewed in context of the genre of yakuza-eiga, or as its own animal. The black & white photography is sharp with high contrasts & extraordinary beauty. There is a long sequence of Murakami & Yoh pursuing one another through dark alleys as Yoh throws knives trying to injure Murakami. This is just one of several sequences that push film noir lighting techniques as far as they can go without parody. Many scenes with no action in them whatsoever are charged with moodiness & suspense due to the camera angles & lighting.

It is not actually a vicious film despite its notoriety for brutality. That Murakami is the ultimate amoral hero, who does not acknowledge the humanity of himself or anyone else, makes him more disturbing than romanticized nihilists. There seems to be no part of him that approves of anything about society, & that may ultimately strike the viewer as a more brutal reality than an all-out bloodfest.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

I'm not so convinced this sort of scapegoating is at all the subliminal message that helped make ninkyo or chivalrous yakuza such a popular idea in cinema through the 1960s. Casting the 1930s military establishment as the bad guys had as much to do with the public's justified anger that made "comfort women" of Japanese girls & told boys still on the child's side of manhood to crash their airplanes into the sides of ships.

I'm not so convinced this sort of scapegoating is at all the subliminal message that helped make ninkyo or chivalrous yakuza such a popular idea in cinema through the 1960s. Casting the 1930s military establishment as the bad guys had as much to do with the public's justified anger that made "comfort women" of Japanese girls & told boys still on the child's side of manhood to crash their airplanes into the sides of ships.

He derives personal release, an actual happiness, in killing. Later yakuza heros of the classic period do not express joy in killing, but have an edge of gentleness that renders them sorry for murderous actions that must be taken for the sake of one's sense of justice or humanity.

He derives personal release, an actual happiness, in killing. Later yakuza heros of the classic period do not express joy in killing, but have an edge of gentleness that renders them sorry for murderous actions that must be taken for the sake of one's sense of justice or humanity.