Daisuke Ito shares with another writer-director, Kaneto Shindo famed for Onibaba (1965), a definite sympathy for peasants & an occasional loathing for samurai. Shindo scripted Chuji Kunisada (The Wandering Gambler, 1960) starring Toshiro Mifune, about the same commoner-swordsman Chuji Kunisada whom Ito chose for a silent film trilogy in the late 1920s. Many of Ito's pre-war films regard the escapades of Tokugawa period gamblers, actors, & commoners, vs the devilish machinations of the samurai class. His social awareness is not overtly political, but issues of injustice & inequality inherent to feudalism is an underlying reality in Ito's films.

Shindo is the more sentimental of the two, & Ito is by far the more intrigued by humor & violence. Though several of Ito's films have long had subtitled 35 mm prints in America, they were mostly shown only in Japanese-American cinemas, the last of which closed down in the 1980s, & he is not a well known director in the west, though he deserves to be.

The English language histories of Japanese cinema generally do speak of Ito's pre-war films, but his last films in the 1960s have remained obscure. This is partly because he did his last work for Toei Studios, a company famed for quickly made B features, chiefly chambara & yakuza-eiga (samurai & gangster genres) which "serious" film historians have dismissed out of hand whenever this studio's name is attached.

But among so much that was indeed merely commercial from Toei, there are some genuinely great films that have been unjustly overlooked.

Some directors were either too political or too elderly for other studios to hire them in the post-war period, & Ito was perhaps both. Toei took advantage of these prejudices to get directors of Ito's calibre for a cut-rate salary. All they wanted in return was for films to be turned in on time with plenty of action in them. Ito could do pretty much what he wanted, even if by stealth.

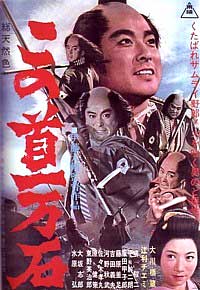

The Retaliation of Gonza (Kuno kubi ichiman-goku, 1963) starred Hashizo Okawa as a lusty laborer from Edo. Supporting cast includes Chiemi Eri, Hiroshi Mizuhara, Sunji Sakai, Shiro Osaka, Kensaku Hara, Kamatari Fujiwara, Shizuo Otomo, & Eijiro Tono.

The Retaliation of Gonza (Kuno kubi ichiman-goku, 1963) starred Hashizo Okawa as a lusty laborer from Edo. Supporting cast includes Chiemi Eri, Hiroshi Mizuhara, Sunji Sakai, Shiro Osaka, Kensaku Hara, Kamatari Fujiwara, Shizuo Otomo, & Eijiro Tono.

Ito's interest in the lower classes gives us an inside-view of a laborer's hostel, in which men sleep & eat & wait for work, usually to have their earnings trimmed by the labor boss who gets a percentage plus deducts all credit extended for meals & a spot on the floor to sleep. What little they had left over would be lost to gambling & drinking, then back to the labor pool they go.

We first meet Gonza as he leads a wedding parade, manipulating a long decorative pole quite well, dancing clownishly, & being admired for his good looks by women along the street. This is one of the nicer sorts of jobs one could get through the labor pool. His next one was to help dig a well in a ghetto area, but he's glad even of such hard work, for his true-love lived nearby.

His girlfriend Chizu (Chiemi Eri) is a tough & pretty daughter of a dottering ronin (Eijiro Tono) who, despite his own poverty & old age, will not allow his daughter to marry a peasant. Gonza wishes he could be a samurai for only long enough to get married to Chizu.

Alas, his next labor duty is with a procession of samurai on its way to Kyushu to honor a lord's newborn child. It means Gonza will be away from Edo a long while, since Kyushu is a forty day trek. After sad farewells & promises of grand reunion, our hero, cute li'l Gonza, is off with the samurai, serving as their spear-carrier.

Ito has all this while been giving us comparisons between the samurai & commoners. The samurai hired laborers because they were cheaper than taking vassals on the extended trip. They hired fewer than they were supposed to, so that they could keep the extra funds for themselves. These samurai were greedy & crooked, but not necessarily dangerous (at first), being themselves awfully low in the pecking order.

When someone lets on that Gonza would like to be a samurai, "Even the lowest rank of samurai," one of the annoyed vassals retorts, "I am the lowest rank of samurai." These are decidedly unclassy representatives of their class, men under a lord with a mere 10,017 koku (rice land) fief. Only one of these men seems kind in any regard, & even he will refuse to help a peasant when the going gets rough.

A much larger procession whose lord has a 497,000 koku fief comes upon the inn in which the small group of Okonogi clansmen are staying with their laborers. The more important clansmen suggest it would be best for Okonogi men to move elsewhere, since it would be improper for their own lord to be put up at a lesser inn. The Okonogi men become pettish, knowing full well that they are being pressured & disrespected because their lord has such a small fief.

Obstinantly, they suggest that only an apologetic act of seppuku will convince them that their moving from the inn is no insult to their dignity. When it turns out that the larger procession is on its way to see the Shogun himself, the Okonogi men are put on the defensive, & tell a critical lie: They claim that they have with them the famous spear Acharamaru which Lord Okonogi had used to save Shogun Ieyasu's life at the Battle of Achara. It would be impossible for such an important weapon to stay elsewhere than the best inn.

The two vassals of the bigger clan return to their lord, who is waiting on the road outside of town with his large procession. The vassals are willing to commit seppuku in order to win the inn honorably, but it is decided instead to buy the Okonoji men off. A retainer takes a sum of money to the inn & the Okanogi samurai sheepishly accept the bribe & move to a lesser inn.

Meanwhile our spear-carrier hero Gonza happened to have injured his toe earlier in the tale, so was late catching up with the others, & unaware that they had vacated the inn. He places the spear outside the inn, then dashes off to visit with a prostitute named Chizuro who happens to look just like Chizu who he has been missing (Chiemi Eri playing a double role).

The large clan arrives at the inn & finds that the Okonogi men have not taken the famous spear Acharamaru with them. Upon inspecting it, they find it is not the famous spear after all. They are particularly annoyed, but decide to pretend the spear is the famous one, & to demand the head of an Okonogi samurai as payment for the return of the honorable spear which Okonogi men were remiss in leaving unattended.

All this while we've come to admire the rowdy, fun-loving workers more & more, & to see how united they are, how moral despite their lusty inclinations & occasional brawls & disagreements. They're not perfect, but they're a lot more well-meaning than any of the samurai, who by contrast are back-biting, petty, self-important, easily corruptible, & when cornered, cowardly.

The Okonogi men cannot admit the spear is not the famous one, for if it becomes known they used Ieyasu's name so blithely, they could end up causing their lord to lose his small fief entirely.

So too all this while the film itself has been rather fun-loving & non-violent, the sort of film Hashizo Okawa often starred in, a tra-la-la happy-go-lucky sort of guy. But Daisuke Ito is using Hashizo's famously smiling sweet-natured character roles with high deception, which will make the real direction of this tale all the more unsettling.

The tone changes quite suddenly. The samurai recall Gonza's desire to be a samurai "just once in my life." They find him at the brothel, quite drunk & giddy. They hire a hairdresser to "play a game" & "see what you would look like as a samurai." Giddy Gonza is eagerly willing, a trusting sort of guy drunk or sober.

The great classic Harakiri starring Tatsuya Nakadai, or the 1960s Shinobi no mono ninja films starring Raizo Ichikawa, the films of Daisuke Ito, & quite a few others, are essentially "anti samurai films" & stand as a startling counterpoint to Kurosawa's upraising of the samurai class above other classes of people.

On a measuring rod's continuum, Kurosawa in films like Seven Samurai assume a gigantic nobility to the class; Mizoguchi in films like Samurai Rebellion assumes noble samurai exist but are not the rule & are therefore at the mercy of the corruption of their masters; & Ito assumes samurai are simply a menace to each other & to commoners.

Gonza's fellow laborers meanwhile are afraid Gonza will be in trouble since he was the spear-carrier & could be blamed for the trouble. Slowly it dawns on them what the samurai must be planning. They sneak into the samurai quarters. When they see Gonza, one of them exclaims, "Oh! Samurai hair!" They run to the previous inn & beseech Boss Chobei, head of the laborers hired by the larger clan, to let them take the spear to save Gonza's life. Boss Chobei is an old man & decides to risk it.

When the samurai Chobei works under find the spear missing, they are at first angry, but forgive him because the spear meant "Trouble for us, too," if any samurai were really beheaded for it. We know at that instant that this richer, more glorious-appearing clan is just as petty & insincere as the poorer & homlier clansmen of Okonogi.

Okonogi men meanwhile are trying to get Gonza's head. Drunken Gonza is very slow to catch on. He barely misses having his head cut off twice, once because a maid appeared with a message & the samurai had to hide their plan, the second time because Gonza fell over from too much sake & the sword passed over his head, resheathed so fast he didn't know how close he came to death.

Finally he is told the only way he can be a samurai is to commit seppuku; then he will receive honorable burial services. This nearly sobers Gonza, who immediately tries to escape, saying, "If it's so honorable, why don't you kill yourselves!" Confronting them with the reality of the position they have put him in, he says: "You call it 'honor' to sacrifice an innocent man?"

By now Ito's theme is fully realized. To carry it further is in many critics' mind gratuitously violent. In reality, to carry it no further is to cheat the audience of a promised grand finale. Critics forget too often that cinema is a prolitarian form of entertainment; or, they associate prolitarian tastes for "lowest common denominator." By this means a great film like Ito's becomes mere "junk" because he lives up to his promise to deliver a complete & unflinching vision.

Ito has championed the prolitarian class up to this point of the film. And he is going to entertain a prolitarian audience with the final, necessary, inevitable carnage.

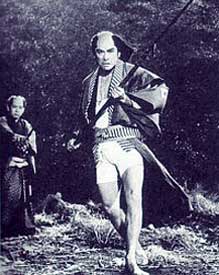

Gonza's fellow laborers arrive & give him the spear, intending its safe return to stop his execution. But the samurai have no way to back down now. Gonza had handled the wedding-parade pole excellently (though comically) in the opening scene. Now we discover his use of the yari spear, though awkward from lack of training, is highly efficient.

By luck more than skill, since he's still tipsy as well as untrained, he proceeds to fight the Okunogi men & kill them one by one, while in a state of angry terror & intense desire to survive.

Ito exploits fully the defensive use of a yari in untrained hands. The graphic potrayal of the spear going through a mouth & out the neck; of a samurai being pinned momentarily to a wall; another having both cheeks opened as the spear passes hirozontally through his mouth... blocks, evasions, close calls... It is no easy contest & our physically beautiful peasant hero is scored along the back, down the cheak, has a broken sword thrown into his right eye...

His new samurai hairstyle comes undone & what remains of his beauty only adds to his monstrousness. The other laborers help him get the last two Okunogi men, then flee lest they become further involved.

The magistrate is coming. He's another corrupt samurai who has promised to kill Gonza & cover up the matter. He has gunners with him. Gonza is already lying as though dead among the carnage.

Chizuku, the girl who was a look-alike for his girlfriend in Edo, arrives to try to help him, but is killed by the first barrage of bullets while Gonza strives hideously for one more stand. Despite the blood oozing from his cheek & mangled eye & his hair wild like a ghost's, he is yet wierdly beautiful, & he smiles when the gunners pellet him the second time, not from masochism but from resignition to his fate, the irony of his wish to be a samurai for a day having come true.

Ito has not portrayed commoners as winners. But he has assured us that only men of ill-will can defend the feudal system, & men of good will are injured by it. Samurai are bad. Commoners are good. Though simplistic, it is certainly a defensible position.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|