Although Sanders of the River (1935) is by no means a musical, by casting Paul Robeson as the city-educated trival chief Bosambo, it would go too far against expectation not to have him sing.

Although Sanders of the River (1935) is by no means a musical, by casting Paul Robeson as the city-educated trival chief Bosambo, it would go too far against expectation not to have him sing.

The music is more than incidental, but in the main is worked into the film's text well enough not to interupt what is essentially a "jungle adventure" straight & simple.

Still, it's an extra treat to hear Robeson sing "Canoe Song," "Love Song" aka "My Little Black Dove"; & most memorably "The Killing Song" aka "The Song of the Spear."

Nina Mae McKinney as Bosambo's wife Lilongo lends her voice to "Love Song" as well, & sings "Congo Lullaby" aka "Lion Song."

These songs were composed by Mischa Spoliansky (music) & Arthur Wimperis (lyrics) with an intent to sound Romanticist in the "noble savage" tradition.

Despite this dubious intent, Spoliansky had enough genius to do it well, & Robeson's voice is so amazing that it all works splendidly, even with lyrics by Wimperis with unintentionally silly rhymes (rattle, battle, cattle). Spoliansky would soon after score King Solomon's Mines (1937) which also starred Robeson.

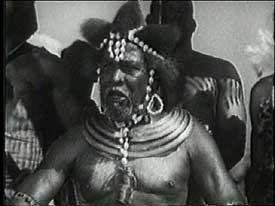

Actual Congo chiefs participated in Sanders of the River, & we see tribal peoples of the Acholi, Sesi, Tefik, Yoruba, Mendi, & Kroo tribes. The documentary footage inserted throughout the film shows the every day lives & celebrations of West African tribal groups of the Congo, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, Guyana, & Liberia, without regard for the story's specific location in Nigeria. Actual Congo chiefs participated in Sanders of the River, & we see tribal peoples of the Acholi, Sesi, Tefik, Yoruba, Mendi, & Kroo tribes. The documentary footage inserted throughout the film shows the every day lives & celebrations of West African tribal groups of the Congo, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, Guyana, & Liberia, without regard for the story's specific location in Nigeria.

In staged native-costume battles, whatever else one thinks of the film's story, it's clear the native actors were having a grand old time. They did not interact with the primary cast, however, who filmed on very well designed sets on the Themes.

Among the London cast was Jomo Kenyatta, who later became president of Kenya, & already a significant community leader when he agreed to appear in a cameo role, expecting, even as did Paul Robeson, a film that represented Africa & Africans much better than turned out to be case.

Sanders of the River has in recent years been most addressed for its paternalistic racism & exaggerated imperialism, often reducing Paul Robeson's work to that of a grinning white-butt-kissing spear-chucker, named, no less, Boy Sambo.

Paul was all too soon sorry he made the film, & it's the only film he ever expressed a desire to disown, as the script he agreed to did not include such a weight of pro-British propaganda which the censors insisted the director add if it were to be released at all, during a sensitive period of British & African relations.

Robeson was no naif & well knew from the start the chance he was taking. It was not the result of later Civil Rights activism that led to a community disdain for good actors typecast as spearchuckers, this was for a very long time a thorn in the side of black intellectuals of which Paul was definitely one. But mightn't that standard role be given authenticity? That was the pressing question for a serious actor.

Paul had meetings with African activists in London to discuss beforehand whether he should accept such a role. Everyone resoundingly thought he should do it, for no matter what else the whites made out of images of Africa, Robeson's inherently dignified & powerful presence could not help but convey a degree of greatness that would otherwise be lacking.

There's a story Robeson would later tell of walking out on the premier, disgusted by how the film came out. Modern historians have called this an invention of hindsight, as Robeson's embarrassment was a couple years in the future after a little too much feedback from his own community leaders.

The truth seems to be that Robeson did walk out, perhaps more depressed than angry, but was pursued & convinced to return to the screening, as Jomo Kenyatta & other friends & supporters were at the premier & he should remain as much in support of them as they of him. So when the lights came up at the end of the showing, Paul had already come back to put the best face on a sorry situation.

Disappointing as the film was, if assessed for what it is, a piece of pulp fiction based on a short story collection by Edgar Wallace, it's not ineffective as a "jungle movie" piece of entertainment. And such films had as likely a shot at political correctness as as a porkroast at Passover.

Disappointing as the film was, if assessed for what it is, a piece of pulp fiction based on a short story collection by Edgar Wallace, it's not ineffective as a "jungle movie" piece of entertainment. And such films had as likely a shot at political correctness as as a porkroast at Passover.

If somewhat forgiven for the context of its time, the paternalism & imperialism truly belongs to the age depicted, & who could expect white & especially English filmmakers to show England anything but a positive influence on Nigeria.

Even today British essays & books about Nigeria almost always allude to it as "the former British colony" & who really could expect a 1930s movie to address the civil unrest against oppressive colonial rule, the mass protests, the Igbo Women's Revolt, the forcing of unnatural national boundaries in order to better siphon the wealth of the nation into white hands, the exploitation of Africans as cheap labor, & support for terrifying warlords so long as they subjugated their people to British interests.

The average British & American viewer of the era might never have questioned the greatness of Empire & the superiority of British rule over tribal peoples. Our personal hindsight is not something that would have entered the minds of the story's while characters.

Instead of the grim realities, we are treated to a view of British rule as benevolent & only strong-fisted when those childlike & naturally violent tribes reverted to their inherent state of warfare, non-monogamy, & lack of prosperity. This film by reflecting an attitude of the age is actually "true" to its contemporary attitudes & can be appreciated as an authentic reflection of colonialist self-image.

Except, of course, the only real reason to watch the damned thing is to see Paul Robeson. And so the film's culturally assaultive narration looms at a modern viewer as awesomely inappropriate.

Robeson acquired a sincere interest in African culture while in England, where he encountered Africans of sundry nations who as members of a Commonwealth were a commonplace in London, unlike in America where African Americans of the time rarely had the opportunity of meeting native Africans, & where the possibility of immigration of large numbers of African people was restricted by legal barriers.

Robeson acquired a sincere interest in African culture while in England, where he encountered Africans of sundry nations who as members of a Commonwealth were a commonplace in London, unlike in America where African Americans of the time rarely had the opportunity of meeting native Africans, & where the possibility of immigration of large numbers of African people was restricted by legal barriers.

You didn't walk through the streets of Harlem seeing folks from West Africa the way you would in London, & this was just one of the many things that lent Paul eye-opening experiences.

And it was due to Robeson's influence on the film while in production that the characters are never reduced to lines like "Bad juju, Bwana," but speak well & convey their own pride, family lives, dreams & ambitions.

Some viewers will not be able to get past Robeson in a skimpy leopard skin parading among fully clad white actors & bowing to Lord Sandy as though Sanders is the be-all & end-all jesus & daddy rolled into one. It's undeniably appalling. But lovers of pulp fiction will recognize a few improvements over the conventions of the African adventure story, which quite commonly included heroic native characters assisting white heros, which Robeson in fact plays beautifully.

Fact is, Lord Sandy comes off as some kind of wuss, & the "tame" & adoring Bosambo a giant of a man who simply must be kowtowing for pragmatic reasons since he's well enough educated to know this Lord Sandy isn't much in himself but represents a lot of spooky power that can be used for Bosambo's own rise among the clans, or against him.

At least, I never for once believed the bowing & scraping was sincere worship of a dork like Sanders. I was willing to suspend disbelief that the brawny & intelligent Chief Bosambo might authentically accept Sandy as a friend & veritable family member, the same way one might have a genuine fondness for any dufus within one's sphere or family.

For reasons of British pride the script makes much of regional commissioner Sanders (Leslie Banks) doing away with intra-tribal slavery, ending war, enforcing peace, & teaching the natives monogamy. The idea that no African suffered under British rule is such an amazing lie that many will not forgive anything else about the film, but try to view it like a story belonging to pulps of the 1930s, which were so much worse than this.

Edgar Wallace's story tried to be at least a little more than imperialist propaganda, & it's fairly obvious Sanders' little enclave of whites would've been eradicated very quickly with resultant all-out-war with England against the natives of Nigeria if Bosambo the educated soldier-chief had not been Sanders' ally.

Edgar Wallace's story tried to be at least a little more than imperialist propaganda, & it's fairly obvious Sanders' little enclave of whites would've been eradicated very quickly with resultant all-out-war with England against the natives of Nigeria if Bosambo the educated soldier-chief had not been Sanders' ally.

And when Tony Wane as Chief Mofolaba first backs down before Sanders, it is not for respect due a superior race, but a calculated withdrawal from an occupation army that possesses machine-guns & a swift willingness to slaughter thousands, never by the superiority of their civilization but only the superiority of their weapons, an occupying force with sufficient disbelief in the humanity of Africans that any number of them could easily be killed without guilt or restraint.

The strong scenes in the story are when Sanders is not visible. Bosambo & his moslem wife Lilongo at home in their village, with their children, are great scenes of domestic love & tribal leadership.

Nina Mae McKinney, who in England was dubbed "the Black Garbo," had very few great roles, & zero great movies to her credit, but she was personally a great actor & all-round talent, as well as an incredible beauty. She has to be appreciated as Lilongo in Sanders & as Chick in Hallelujah (1929), as there just isn't better to see her in.

When the rival Chief Mofolaba (Mo Fo, ha ha ha) kidnaps Lilongo & Bosambo strides into the enemy village alone, with every intent of saving his wife without violence, it is a stupendously heroic moment, worthy of the best of pulp fiction. Through this part of the tale I was scared shitless for Lilongo, who Mofolaba had every intention of slaying in front of his enemy's eyes, with no real chance of peace between them.

And though the paterialism of the tale rises again when it is Sanders who races to the rescue, if you look closely at these scenes, you see that it as much Bosambo who saves Sanders.

And gads, the very idea of a white district commissioner risking everything for the life of one man whose family he cares for is not in that moment political or self-serving or great-white-burden, it is about mutual friendship between him & Bosambo. So even if you have to look hard to find it, there are things in this film that rise well above its overall neenerisms about the great & godly propriety of imperialism.

A decent budget & the best intentions of the director & producer failed to deliver a film that is genuinely fair to Africa & Africans as was intended. That it is afflicted with the same flaws as any Z-budget jungle flick says a lot about the inability of the British to overcome their own agendas & racisms, different in type though these faults may have been from parallel American agendas & racisms.

Even so, Nina & Paul are wonderful. If a viewer can momentarily embrace pulp adventure fiction as jolly good fun, a lot of entertainment value & pride can be found in these two performances. That whoever the hell played Sanders leaves no more impression than a sandbag tells us more than does the script's delight in imperialism.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|