IIt is so hard to make top-ten lists of anything, but any list of "top ten samurai films" easily leads off with Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (Schicinin no samurai, 1954).

IIt is so hard to make top-ten lists of anything, but any list of "top ten samurai films" easily leads off with Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (Schicinin no samurai, 1954).

Harder is to make a top ten list of the whole of world cinema. But there are a few films throughout my life have refused to get knocked off the very tippy-top of my favorites.

It's the rare film I'd even want to see twice, but rarer still are the ones I must see every few years if not oftener, always getting something new out of them.

Besides Seven Samurai, some of the other films that have become part of my very being, enriching my life lastingly & recurringly, & which pop to mind soonest whenever I think of a world-wide "top ten," include such as these, in no particular order:

Marcel Carne's Children of the Paradise (Le Enfants du paradise, 1945), Wojchiech Has's The Saragasso Manuscript (Rekopis znaleziony w Saragossie, 1965), Luis Bunuel's The Exterminating Angel (El Angel exterminador, 1962), Masaki Kobayashi's Harakiri (Seppuku, 1962), Frederico Felllini's La Strada (The Road, 1954), King Hu's A Touch of Zen (Hsia nu, 1969), Roberto Gavaldon's Macario (1960), Carol Reed's The Third Man (1949), & the only director to appear twice in these lastingly influential choices, Kurosawa again for Ikiru (To Live!, 1952).

And that's the dangerous ten. Even that's not easy to do, for fear it's cast in stone, for fear I'll remember a half-hour from now some film that changed forever this world of dreams. One begins wondering should it really be Kobayashi's Harakiri instead of the "Hoichi the Earless" episode of his Kwaidon (Kaidan, 1964)? Is The Third Man a better film for English language inclusion than Casablanca (1954) or something slightly off the wall, but hey, how about The Night of the Hunter (1955)?

Or, do I for sure prefer La Strada to Fellini's Casanova (1976)? For wuxia, is King Hu's Touch of Zen for absolute certain more powerful for my tastes than Ho Meng Hwa's The Lady Hermit (Shong kui niang zi, 1971)? And what about Fritz Lang's M (1931). Wouldn't some example of German Expressionism belong in any serious top-ten instead of doubling up on bloody samurai films? And so on until it's obvious I need a top-100 favorites-list just to get started.

But what is unchanged in every permutation, Seven Samurai is always present.

I've long put off writing an article on Seven Samurai because it has been written about endlessly by hundreds of film critics & historians.

I've long put off writing an article on Seven Samurai because it has been written about endlessly by hundreds of film critics & historians.

I wanted first to bring attention to a lot of neglected films before I got round to Kurosawa who has so much coverage elsewhere.

I was also leery of writing something poorly about which others have written so well. And while I could easily lavish praise on Seven Samurai all day & all night, in fact I have a certain approach & analyses that some may find insulting, & who wants to insult one of one's own favorite films?

What finally got me to break down & start this essay was someone who wrote me a hostile letter insisting I knew nothing whatsoever about Japanese cinema or Kurosawa & should try boning up on my subject by reading this & that book which, of course, I had already read.

My unfriendly attacker posited absurdly that I'm ill-informed about Japanese cinema. I guess he'd read selectively only the Kurosawa reviews already accessible at the Weird Wild Realm. My unfriendly attacker posited absurdly that I'm ill-informed about Japanese cinema. I guess he'd read selectively only the Kurosawa reviews already accessible at the Weird Wild Realm.

He had detected my "approach & analyses" to Kurosawa correctly enough. But being otherwise a boob, he interpretted this approach as akin to saying Kurosawa was a rightwing bonehead, & out of misguided chivalry (giving the chap the benefit of the doubt) thought he should write an angry email in the dear ol' Taisho's defense.

In being a stand-up guy for his favorite director, he decided to allege that Kurosawa was a leftist, & how dare I call him conservative. Inherent in my angry emailer's hostility was his own belief, not shared by me, that conservatives cannot be decent & humane, & that by insisting Kurosawa was both a conservative & a classist, I had called him a heartless pro-fascist son of a bitch. Whereas, apparently, I was supposed to declare him a Socialist & great humanitarian.

Others have already taken that approach. It is in fact so often alleged that Kurosawa is a left-leaning "tendency film" advocate that's almost like film historians are just copying out of each others misguided assessments. And my angry critic put me thinking about Kurosawa's artful blend of humanity & conservatism, why anyone should mistake that for a lefty, & thus erupted thoughts regarding his entire output but especially Seven Samurai.

So while I might've been offended by some boob writing to tell me how ill-informed I am about Japanese cinema & so forth, I may owe him a hat-tip of gratitude for bringing some haphazard thoughts about Kurosawa's greatest film nearer to cohesion.

It takes no great leap of reasoning ability to find Kurosawa a conservative & traditionalist, which is not to be mistaken for rightwing politics, words like "conservative" being more loaded nowadays than they should be.

It takes no great leap of reasoning ability to find Kurosawa a conservative & traditionalist, which is not to be mistaken for rightwing politics, words like "conservative" being more loaded nowadays than they should be.

Kurosawa's youthful flirtation with leftist philosophy didn't go very far or last very long because it did not fit his heart. In his most sensitive films he finds an apolitical humanist stance which says, essentially, as in Ikiru, that it's sad to have lived one's life achieving nothing, pursuing no dream, being a cog.

But he cannot bring himself to posit that the larger society -- government & social norms -- have gone seriously awry, politically & spiritually, to render so many people only cogs. If only the most greatly heroic, or the desparate & dying, can rise above what appears to be inevitabilities, then society itself has failed. Kurosawa lacks such insight.

His vision is purely conservative when he imagines a world wherein heroic samurai assist weak, stupid peasants incapable of helping themselves. His vision is purely conservative when he imagines a world wherein heroic samurai assist weak, stupid peasants incapable of helping themselves.

Keiko-eiga or the left-leaning film movement was over before Kurosawa started directing, but in its lingering influences he contributed between little & nothing.

Lefties selected either a peasant hero or a peasant victim, or showed the hypocrisy of samurai ethos & the destruction of anything good in favor of the status quo, defense of the samurai ethos being folly. And while it is easy to criticize the inherent injustice of feudalism, for lefties such critique is generally a veiled criticism of modern militarism, nationalism, and/or capitalism.

Kurosawa couldn't even begin to think in such terms, because he believed in his own class heritage, which was samurai class, as superior to others. If he would never say so, he would certainly show it to be so, time & again, in his films.

And he treated people accordingly in his actual life. He was a great man, no doubt about that, but not a nice friendly man to anyone who failed to kowtow appropriately. And this contributed to the fact that he was also an unhappy man, a lonely intellect not because his thinking was legitimately above all others (it was distinctly not so), but for having placed himself on an unsteady pedestal.

When someone expected to be treated as an equal, Kurosawa was not warm & pleasant & eager to embrace others as his peers, even if they were.

When someone expected to be treated as an equal, Kurosawa was not warm & pleasant & eager to embrace others as his peers, even if they were.

A tragic example is when he jettisoned all future relationship with Mifune for getting too big for his britches, thus losing the greatest asset of his own filmmaking career.

My perception of Mifune the man is that he was humble & decent beyond necessity, in no way deserving Kurosawa's essential betrayal. Since that betrayal did not serve Kurosawa emotionally or materially, it can only be understood as a self-damaging flaw in his character.

Or when he pitched pure hatred at Shintaro Katsu to the detriment of the value of his own film Shadow Warrior (Kagemusha, 1980) which required someone like Katsushin who could by turns convey either peasantry or nobility & was perfect for the double-role.

By contrast his replacement, the compliant Tatsuya Nakadai with his Shakespearean air, has such noble bearing that when plalying the peasant he seemed more like a painted clown & nowhere near the real deal. By contrast his replacement, the compliant Tatsuya Nakadai with his Shakespearean air, has such noble bearing that when plalying the peasant he seemed more like a painted clown & nowhere near the real deal.

That is not to say Katsushin couldn't be a complete shithead & nuisance, but for the sake of one's own art, one bares up to the eccentericities of fellow artists if the work & the art takes precedence over the ego. Due to ego, Kurosawa turned against people whose assistance to his own projects could not be equalled by anyone else.

And it's my contention that it was this same misguided egoism that defined the manner by which he assumed, & conveyed, the nature of the samurai class, his heritage, as greater & prettier & more glorious & more significant & even more humane & decent than other classes & types of people. Certainly the parallel is present between how he conducted his troubled professional relationships & how he depicted fictional ronin as requiring nothing but themselves.

These self-sabotaging errors of Kurosawa's life were what arose when someone failed to call him Taisho (Emperor) & failed to treat him as Taisho. Well, he was not Taisho, he was a man, depressive & suicidal, & that doubtless helped make his work become emotionally real. He wasn't a bad man & he certainly was one of cinema's greatest artists, but he used that art foremost to uphold the superiority of his own class heritage.

Kurosawa was (whether or not tepidly) a nationalist even at the height of the worst atrocities of the Sino-Japanese & Pacific War. He was not a raging example thereof, & was not blind to cruelty & injustice. Being as a nationalist at heart, he was never at risk during the war years as were leftist directors. Kurosawa was (whether or not tepidly) a nationalist even at the height of the worst atrocities of the Sino-Japanese & Pacific War. He was not a raging example thereof, & was not blind to cruelty & injustice. Being as a nationalist at heart, he was never at risk during the war years as were leftist directors.

As a traditionalist-conservative (a more apropos category than rightwinger), it was not hard for him to knuckle under to the imperial military requirements for cinema to support the war. Only afterward when it became easy & even a fad did he reveal he never especially liked fascists.

As an artist, he lacked the guts to criticize at moments when it would count; he was no Sadao Yamanaka doomed to be sent to the front as a punishment from which he would never return; or Satsuo Yamamoto, who did make it through to continue making films, explicitely about war as an evil that makes men evil.

When the war was over & anti-war films were a dime a dozen, Kurosawa made his closest thing to a tendency-film in No Regrets for Our Youth (Waga seishun ni kuinashi, 1946), about the persecution of a leftist.

Alas it's not much of a film, & far, far better anti-war films were to be made by others, including Kon Ichikawa's The Burmese Harp (Biruma no tategoto, 1956), Masaki Kobayashi's monumentally horrific The Human Condition (Ningen no joken, 1959), Alas it's not much of a film, & far, far better anti-war films were to be made by others, including Kon Ichikawa's The Burmese Harp (Biruma no tategoto, 1956), Masaki Kobayashi's monumentally horrific The Human Condition (Ningen no joken, 1959),

Kurosawa's other anti-war film is really only an anti-atomic bomb film & so no more meaningful than Godzilla. A-bombs suck, sure; that's too-easy a subject, & deflects criticism away from Japan entirely. With I Live in Fear: Record of a Living Being (Ikimono no kiroku, 1955) Kurosawa trivialized what Kobayashi did with enormous vigor & Ichikawa composed with tragic poetry.

So with both I Live in Fear & No Regrets for Our Youth, we're not talking about films of his very soul. He would not be even on the secondary lists of great directors if these were the best he could do.

By contrast, when he made They Who Step on the Tiger's Tail (Tora no o wo fumu otokotachi, 1945) it was to please the war interests with a great nationalist hero, Yoshitsune, selflessly adored by his chief vassal Benkei, who would die for him.

And Kurosawa was shocked that the government who wanted just such films paranoically suggested the film's best scene, Benkei's drunkenness, was a criticism of the military, when Kurosawa had no such criticisms in mind.

He took some critical flack after the war for his willingness to make films in support of Imperialism, including The Most Beautiful (Ichiban utsukushiku, 1944) which makes it heroic to work in factories in support of war, & his two Sanshiro Sugata films (1943 brilliant, 1945 not brilliant) encouraging young men to obey their elders & become strong warriors.

I don't fault Kurosawa morally for any of this; it just is what it is, & what is seems to me to infuse his film art.

If one brief statement would convey what I mean it would be this: If one brief statement would convey what I mean it would be this:

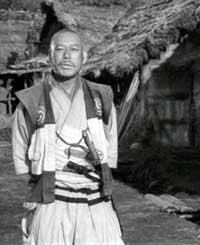

In Seven Samurai, peasants are helpless unwashed cowards & betrayers. The only strong peasants are bandits without scruples. A peasant who wishes he were a samurai (Toshiro Mifune) is a bravely ignorant retard. Only true samurai are capable of effective heroic action.

That's the essence of what Kurosawa conveyed, & conveyed often enough that it's evident it's what he believed. It's the essence of what he infused into his art. And that is the very epitome of Japanese conservative thinking. Yukio Mishima would've gotten along with him on that level.

What his films can't admit is the samurai class was not "the flower of Japan" but an albatros at the neck of decent peasants who seriously never needed them. And Japanese history does not support Kurosawa's vision of wholesome heroic samurai as benefactors to cowardly unbathed peasants.

This went deep in the man's soul & it's in nearly all his films -- which romanticize feudal values & accept the class system. He conducted his directorial habits like a feudal lord, banishing those who were insufficiently submissive until his odd behavior & sense of a daimyo's abject entitlement hampered even his ability to get work.

In his fantasy life of fictional constructions, his peasants are stereotypes. The fact that he has enormous sympathy for them causes many to view him as humanitarian critical of injustice toward the downtrodden. But his sympathy for peasants is that of a sentimentalist who hates to see a dog abused, the same dog he could easily put to death as the humane alternative to cruelty.

So too his women tend to be simpering weak creatures, like the hair-shortened maiden of Seven Samurai whose presence is the one huge note of absurdity in the tale. Supposedly disguised as a boy, the "disguise" wouldn't fool a nearsighted priest at eighty paces.

So too his women tend to be simpering weak creatures, like the hair-shortened maiden of Seven Samurai whose presence is the one huge note of absurdity in the tale. Supposedly disguised as a boy, the "disguise" wouldn't fool a nearsighted priest at eighty paces.

His rare "spunky" gal in Hidden Fortress (Kakushi-toride no san-akunin, 1958) is an even worse cartoon character in a miniskirt, who struts like she could do something but never does.

Lady Asaji of Throne of Blood (Kumonosu jo, 1957) as femme fatale becomes the anti-hero's scapegoat for being such a bad apple. In most of his films the female characters take such backseat positions they might as well not be there at all.

Sometimes in his films the only women who are heroic are prostitutes, & their heroism is in their capacity to love some ineffectual man completely, or not become bitter by their lot in life, or just to suffer without complaint.

His posthumously filmed The Sea Is Watching (Umi wa miteita, 2002) is the strongest of his films glorifying hookers, but the heroic or the suffering sex worker will also be encountered in Ikiru, The Lower Depths (Donzoku, 1957), & other films, including a co-scripted & abominable romanticization of wartime "pleasure women" in Escape at Dawn (Akatsuki no dasso, 1950) which concocts a fable about women's experience in Manchuria that rises to the level of an abominable lie.

Rather like Ozu, Kurosawa had a whoremonger's heart & romanticized hookers almost as much as samurai.

The poetry of his films works best when presented from the perspective of the male upholding a single class's right to carry & sword & kill at will.

If you want to see samurai films that honestly lean to the left, & are legitimately humanitarian rather than sentimental toward injured puppies who are less than human, don't look to Kurosawa, but to the films of Daisuke Ito, Kaneto Shindo, Hideo Sekigawa, Satsuo Yamamoto, Kenji Mizoguchi, or of course Sadao Yamanaka's surviving legacy, Humanity and Paper Balloons (Ninjo Kami-Fusen, 1937), & prepare to have your heart broken.

If some of this sounds so critical as to condemn, it is only because it's an eggheady analysis from the mind, not from the heart.

If some of this sounds so critical as to condemn, it is only because it's an eggheady analysis from the mind, not from the heart.

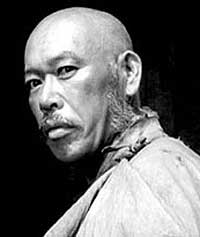

From my own heart I am deeply impressed with the selflessness of Kambei Shimada (Takashi Shimura, one of the greatest actors who ever lived) when he shaves his head, losing status along with his topknot, in order to pose as a priest & save the life of a random child.

Or when Mifune as Kikuchiyo crazily, bravely, clumsily, stupidly gives his life on the bridge, I felt so deeply sorry for him, for the folly of his dream & pretence of being a samurai.

The fact that the peasants who hired them are treacherous, unwashed, & cowardly doesn't seem a necessity for these samurai to have come off as great men each in his own right.

But Kurosawa thought otherwise, & making peasants scum without exception does make it all the sadder that some of the higher grade of humanity, i.e., these six noble samurai plus one bold fool, have put their lives on the line, some to die, for disgusting subhumans who could never deserve such sacrifice.

So when the perpetually calm ultra-swordsman Kyuzo (Seiji Miyaguchi) falls into the mud, not because met by greater skill, but to a sniper's bullet, I was afflicted with abject gloom that such beauty & grace should thus be extinguished. So when the perpetually calm ultra-swordsman Kyuzo (Seiji Miyaguchi) falls into the mud, not because met by greater skill, but to a sniper's bullet, I was afflicted with abject gloom that such beauty & grace should thus be extinguished.

And I easily embraced the idea that such a swordsman could become invincible in any battle which pitted skill against skill, but had no place in a changing world when any bandit son of a bitch might have a gun.

The moments that move me in this film are numerous, & while I noticed that only samurai have real personalities & histories while peasants & bandits are for the most part wicked members of a faceless horde of unworthies, I even so loved these few men as Kurosawa intended we all should.

The visual beauty, the poetry of motion & emotion, are so extraordinary that the film's failings (the absurdity of the pretty peasant girl; the malignant attitude against peasantry) simply shrink away into a symphony of spirited & tragic heroism.

Much more could be written of this film. A whole essay could be written just on the amazing musical score, perhaps the best any action film ever possessed before Sergio Leone, who of course was inspired by Kurosawa.

But so many others have written so much so well about Seven Samurai that I won't rehash the better-covered themes among commentators. I have presented my own themes, whether they induce further hate-mail from boobs convinced Kurosawa is Mother Theresa, or makes a few people ponder a little more deeply a thing each of us do treasure.

Enough to conclude with the unwavering sentiment that this is one of the films every human being who loves cinema should see more than once. No life as a film fan can be complete without immersion into the world of Seven Samurai.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|