Dead too soon of throat cancer in 1984, & still young-looking in his fifties, Hashizo Okawa created many wonderful characters during his film & television career, including the almost-gender-bent Shingo Aoi, in two sets of four films each in which he plays a momma's boy with a sword.

Hashizo designed his own bordering-on-effeminate costumes for those films. When still a youth, he had been an onnagata (player of female roles) in the kabuki theater, & it took some while adjusting to his "samurai hero" roles for cinema after he arrived at Toei Studios in 1955.

Hashizo designed his own bordering-on-effeminate costumes for those films. When still a youth, he had been an onnagata (player of female roles) in the kabuki theater, & it took some while adjusting to his "samurai hero" roles for cinema after he arrived at Toei Studios in 1955.

In the first couple films in which he is supposed to be a samurai, you sort of half expect Hashizo to say "take that you!" as he flops forward with his sword as though it were his purse. Years later Hashizo admitted he was humiliated to see his own fighting scenes in that early film footage. So he began studying fighting techniques for real, which paid off wonderfully.

But with Shingo's character he fused the two aspects of his acting ability & created a masculine hero (or at least a spoiled boy who throws temper tantrums) with a feminine soul, which was supposed to represent Shingo's samurai paternal half (ill tempered boy) & his peasant maternal half (delicate sensitive girl).

The "design" of Shingo -- the wig, inked hairline, & heavy make-up -- is sometimes rather drag-queeny. But in the main, the character design has considerable beauty with just a little Kabuki excess preserved.

The series is about a Shogun's bastard son, who Shogun Yoshimune dares not acknowledge for political reasons. It's about the young man's attempts to impress his absent father from afar, a father who in who in fact secretly loves & protects Shingo.

After all sorts of heroic mayhem in multiple films, the "Shingo's Challenge" trilogy nevertheless concludes with him giving up the sword & living happily ever after as a peasant rice farmer with his mommy.

Imagine such a series shown in some tough American inner city cinema house. Afterward, all the sissies who attended the films come out puffed up & getting menacing at the gangbanger homeboys, who back down trying to save face with "I ain't fighting you, bitch" routines.

Clearly in Japan there was no sense of whimsy or weakness in the idea of a partially effemininate ultra-skilled swordsman. There is no irony in being girlishly pretty & a deadly fighter, as there no doubt would be if an American action film attempted to present such a ambiguous figure of manhood. This is only part of what lends a superior quality & originality to the Shingo Aoi films inspite of these films commonplace action premises.

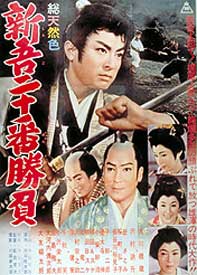

Shingo's Challenge Part I (Shingo ni-juban shobu - dai ichibu, 1961) gets off the ground the unexpected slogan "The life with no peace of mind is a life of fencing."

Shingo's Challenge Part I (Shingo ni-juban shobu - dai ichibu, 1961) gets off the ground the unexpected slogan "The life with no peace of mind is a life of fencing."

Shingo Aoi has built a reputation as Japan's Number 1 fencer, an achievement previously outlined in an earlier set of four films, Shingo's Ten Duels (Shingo juban shobu, 1959-1960). These earlier films were somewhat confusingly retitled the Shingo's Original Challenge parts one thru four, & some commentaries to the two series have since become garbled.

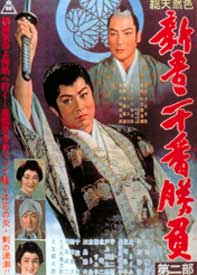

More precisely there were four films in the Ten Duels series, a trilogy of Challenge films, & a final "Extra Challenge" film, for a total of eight. So numbering of the series by varying references can be confusing, too, as they are properly numbered one through four, one through three, plus one, but sundry variations are encountered. Even in the original Japanese there is only one syllable difference from the overall series titles, Shingo juban shobu for the Ten Duels set of four, & Shingo ni-jubon shobu for the Challenge trilogy, the last film alone being distinctly titles, Shingo bangi shobu.

Biographical basics are not recapped for the second series but allusions are continuously made to earlier events. It helps to know that when Shingo was born he was not acknowledged by his father the Shogun, & he was supposed to be sent into exile with his mother Koi. But Koi's original betrothed Mazaki Shozaburo, a master swordsman, kidnapped the infant & raised him as his own son.

Practically weaned on swordsmanship, he was a teenage boy before he learned his origins, & set out on a quest of swordsmanship full of conflicting emotions. He somehow managed to blame his true father the Shogun for all his angst & confusion & developed an irrational hatred for him. But he had equally irrational sentimental feelings toward his mother, who he instantly romanticized & deeply loved. The reality was that he knew neither one of the, & by deciding the pursue swordsmanship on a sort of perpetual "knight's journey" he was able to put off meeting them.

At this stage in Shingo's career, as the first of Challenge or fifth Shingo Aoi film opens, he has already gained a national reputation because of his defeat of Takeda Isshin, the previous barer of the purported Number 1 standing. The "secret" that he is the Shogun's bastard son is by now generally well known, as is the fact that he must remain unacknowledged due to issues of succession.

So he both is & isn't a member of the ruling Tokugawa family, with a piece of rice-baring land assigned to him so that he is independenly wealthy, but without other perks & privileges of his lineage.

The extravagant success of his swordsmanship which the earlier series established has, for the new series, proven less rewarding than expected. For it means Shingo can't even take a nap with ease, needing always to be alert for challengers jealous of his claim to being the nation's pre-eminant fencer, & eager to take his title.

Rokuheita (Minoru Chiaki) demands to be Shingo's student & dogs him. Shingo does not want to be saddled with an acolyte, but can't seem to shake the man. Since Rokuheita has supernaturally acute hearing, he is useful in avoiding danger.

Yajiro is a wretched ronin who wants to kill Shingo, since obviously to kill the best means being better than the best. Their first duel is interupted by an old man whose footsteps had previously awakened Shingo from uneasy sleep, for he recognized a hidden power in the old man even from his foot treads.

The old man, Notomi Ichimusai, is a monkish, retiring fellow, but a great swordsman without question. He was the wild ronin's sword instructor. Despite Shingo's supposed status as the best in the nation, the reality is that this ronin could well outmatch him, since the good publicity of official duels & their official outcomes does not always line up with reality on the ground.

The Shingo Aoi films are among the prettiest for physical posturing with swords. The tableaus before fights are engaged, & sudden new tableaus between each clash of sword, are beautiful moments to behold, & would seem to encourage a cultural notion that sword-posturing represents manhood. The Shingo Aoi films are among the prettiest for physical posturing with swords. The tableaus before fights are engaged, & sudden new tableaus between each clash of sword, are beautiful moments to behold, & would seem to encourage a cultural notion that sword-posturing represents manhood.

The series surely inspired many a Japanese kid with stick or toy sword to strike just such showy postures, & when old enough, to enroll in some dojo. These are after all kids' movies foremost, but with enough substance to Shingo's character to merit adult viewing too.

The Shogun throughout this series, played by Ryutaro Otomo, can get a little tiresome for being portrayed as such a gentlehearted & generous fellow, who ignores his son only out of political necessity, personally suffering for his nation, & secretly weeps with love for Shingo. It's a damned strange fantasy that seems to encourage an unfortunate reality in Japan even to this day, that men are generally absent fathers with greater fealty to their employer than to their family.

Shingo may intellectually understand why his father never sends for or acknowledges him, but emotionally he never accepts it. He is full of anger against his dear old dad, as opposed to his almost slavish devotion to he greatly loved though equally absent mother.

Yet even when he learns his father keeps close tabs on him, it only makes him madder. It will turn out that his self-selected servant/acolyte Rokuheita is actually in service of the Shogun. Plus Sanuki, one of the Shogun's chief vassals, orchestrates a veritable ring of spies that report back to the Shogun about his son, chief among whom are Rokuheita, & Sanuki's own daughter Nui. Nui loves Shingo & serves Shingo's mom as a maid & is her messenger. She nevertheless reports whatever she finds out to her father, who in turn reports to the Shogun.

Sanuki's daughter additionally helps Princess Yuki (Satomi Oka), who also loves Shingo, reconnect with the object of her affection. By the second Challenge film they behave more like rivals for Shingo's affections, but in the initial chapter Nui lives to serve.

Yuki had previously left the court & lived under the assumed indenty of Otaka (in the Ten Duels series), & that was when she fell in love with Shingo, & he in a fickle manner with her. But when he found out who she really was, he became distant, & she would ultimately return to her rightful position at Edo Castle. She longs to be Otaka again, to be Shingo's sweetheart.

Everyone has Shingo's best interests at heart, but it's not all that surprising to think a grown man, however young & idealistically naive, whether or not he has felt neglected by his father his whole life, would get peevish to discover just about everyone he befriends & likes is tattling to daddy about every move he makes.

It's hard to tell from the script whether the writer understood Shingo's recurring temper against his father has large justification, as Hashizo plays Shingo in these moments like a small boy having a temper tantrum, his father being largely faultless.

The Shogun feels the necessity to secretly protect Shingo because there are factions within the shogunate who would either use him against the established line of succession, or kill him for fear of any future claim on the inherited position of Shogun.

While his mother lived exiled Shingo's existence was of small concern to rival factions. But when Koi is recalled to the Shogun's court as a favorite, factions begin to fret he will make Shingo, his actual eldest, primary heir, & move against him, Shingo all the while having no direct contact with any such court intrigues, devoted as he is to wandering & improving his swordskill as a method of spiritual toughening.

Shingo meets an expert pickpocket/thief Seisichi who is a good actor, who can pose as a woman if need be, or as a samurai though he's a peasant. He'll turn out to be a ninja, but one who has Shingo's well-being at heart. He's counterpoint to Oga Jinzo, an evil ninja whose mission is to take Shingo's life.

Seischi being a pretend-pickpocket but actually a ninja protecting Shingo extends the series' curiously consistent subtext that duplicitous friends are the best kind, vis, friends who are never completely honest with you about who they are & what they're up to are the ones you can rely on. Only villains like the unruly ronin are ever totally upfront about what they're doing.

Yajiro the wild ronin wants to finish their duel, & challenges Shingo during a fierce storm, which makes for a nice sequence. The Iga spy Oga Jinzo throws darts to assist Yajiro, so that the ronin wins. But Yajiro never wanted the duel to be a cheat. He fights Oga Junzo lest it become known his defeat of Shingo was not strictly above-board.

Yajiro's teacher Notomi Ichimusai finds Shingo at the base of the a cliff where he fell after being defeated by Yajiro with the dark ninja's assistance. Ichimusai nurses Shingo in his hermit's shack. He feels a deep responsibility for having trained so poorly selected a disciple as Yajiro, & will reveal fighting techniques or philosophies to Shingo useful in defeating Yajiro.

Being emotionally in many ways a silly little boy, Shingo wants to duel the old man who saved him, & petulantly refuses to be turned down. He draws on the old man, but is defeated instantly even though Ichimusai was armed only with a bamboo stick. He tells Shingo, "The right attitude can make your fencing unrivaled. It is not good to swing recklessly."

"I'm sad," Shingo later admits to himself. "Am I the best fencer in Japan?" It's clear to him that the old man is better. His defeat of Takeda Isshin only gained him an illusory title. His self-confidence is shattered by Master Notomi Ichimusai. Yet Shingo can only assert deep in his heart, "No matter how harsh & painful the path may be, I will stay with fencing."

Yajiro meanwhile is "up to no good" again, terrorizing a royal messenger's entourage, forcing them to pay him to stop threatening them & leave. Shingo intervenes & Yajiro promises they will meet again.

But it is Master Notomi who tracks down Yajiro & defeats him with his bamboo cane. Yajiro waits to be killed with his own sword, which Master Notomi has easily taken. But the great fencing master loves Yajiro as a son, even if he is a black sheep. He thought he could do it, but he cannot kill the beast he created.

This is an extremely moving part of the film, like a fable of a family in crisis, & serves as an "interior climax" to this episode of the life of Shingo & satelite figures like Yajiro.

Shingo Aoi films tend to be very loosely plotted like a string of short stories within a single episode. The last story in the first episode hinges on politics & how Shingo is snared by shogunate intrigues without trying to be involved.

He gives a well-intended donation to the Emperor for a shrine restoration, but there is a ban on members of the Tokugawa family contributing such funds. Shingo as a bastard of the Shogun failed to consider appearances.

Everyone involved with his good intentions must be punished one way or another. Kindly Sanuki may well have to slit his stomach. Shingo's mother will also be involved. Princess Yuki begs to be blamed, as she would gladly die for Shingo.

The convoluted intrigues are not the most interesting bits of this film, & Shingo should've predicted all this besides. Fortunately whenever one of the string-of-tales within an episode is weak, it's soon exhausted & over with.

His mother Akoi goes into confinement & the Shogun must more than ever distance Shingo from the bakufu government or any degree of acknowledgement. The Shogun suffers dramatically for these political necessities, as both Akoi & Shingo are dear to him.

When intriguers finagle a legal order to punish Shingo, he fights & kills men sent to arrest him. He incorrectly blames his father for it, & throws one of his infamous temper tantrums, getting super-mad at daddy.

Temper Tantrum Devil Boy breaks into Edo castle screaming angrily with patricidal fury, not knowing his father has already that day been able to resolve the troubles Shingo instigated with his imperial donation.

When Shingo finally comes face to face with his father, he sees the Shogun is weeping, & he breaks down like a little boy full of his own tears too. He flees from the emotional moment, failing to complete the great meeting of which both have dreamed.

How much legitimate history can be detected in Shingo's story? Well, it's 99 percent fiction, obviously, but context is at times surprisingly credible.

Historically speaking, Shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751) did muddle the rules or expectations of inherited rule somewhat, as he was himself an interruption of the general premise that a son of a Shogun would inherit this signal position. He was of a different Tokugawa branch than previous shoguns, the boy-shogun Tokugawa Ietsugu having died at age seven years far too early to have sired a proper heir. So shifts in the pattern of inheritance could well have been on the minds of court ingriguers.

Shoguns were inherently conservative in nature & a great portion of Yoshimune's rule could be likened reactionary. Still, relative to other shoguns, Yoshimune's rule had liberal aspects, especially insofar as he encouraged foreign studies of science & technology that were formerly banned. So perhaps the smily-smily version portrayed by Ryutaro Otomo isn't totally absurd.

But most of his "good" reforms were financial rather than social, & while he was an able national governor, the glowy fictional chap Otomo plays really is mainly a comic book revision. Nevertheless, the tale of Shingo's financial snafu which caught him up in unwanted intrigues is actually a pretty reasonable fiction to impose on a Shogun whose financial reforms were his chief legacy.

It's also a fact that in a time of peace when martial skills were deteriorating in Japan, Yoshimune placed a renewed significance on the samurai class's relationship to swordsmanship as the highest spiritual & physical attainment. So if he had had a bastard son who pursued fencing with Shingo Aoi's singlemindedness, he would indeed have been proud.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|