Shura (1971) carries the subtitled print title of Shura: The 48th Ronin, giving the impression that Shura is the name of the film's antihero, which is soon discovered not to be the case.

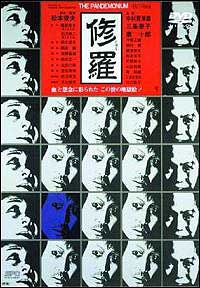

But nowadays the film tends to be given simply as Shura & I like that best. But it has also been distributed as Pandemonium which is a lousy title; as Bloodshed which is awfully generic for a samurai film; & as Demons which is finally correct, the term Shura being derived from asura, a sanskrit buddhist/hindu name for a demon. But nowadays the film tends to be given simply as Shura & I like that best. But it has also been distributed as Pandemonium which is a lousy title; as Bloodshed which is awfully generic for a samurai film; & as Demons which is finally correct, the term Shura being derived from asura, a sanskrit buddhist/hindu name for a demon.

Shura is sometimes regarded as a specific asura, a dark god who suffers & declines unless steeped in constant warfare, for which he eternally hungers. The word is additionally a Noh drama term for for a type of play about ghosts or suffering warriors, which would be a dead-on description of the gloomy haunted protagonist of the film.

1971 may seem awfully late for a black & white samurai film. But Shura is of a very special sub-genre of "cruel jidai-geki" which by tradition were filmed in black & white to enhance the horror of the situations. In the late 50s & 1960s when most "fun" samurai films with smiling heroes were in full color, "serious" doomful films were still in black & white.

Cruel jidai-geki was kind of the last stand for film noir in which nihilistic samurai followed paths of destruction & self-destruction in worlds of shadow. And Shura is the last great example of cruel jidai-geki in its purest form.

Shura actually begins with a full color image of the sun going down. As the demon-haunted night descends, the film becomes b/w, & gets increasingly dark as the characters come closer & closer to madness.

Washing the color out of the opening scene is like "announcing" this is a cruel tale, & the director pushed the cinematographer to extremes to capture sharp images of character's faces amidst the deepest of sinister shadows. It's a world wherein occasionally the only thing visible were lanterns, or a few facial elements leaning into candlelight, almost like disembodied spirits. Washing the color out of the opening scene is like "announcing" this is a cruel tale, & the director pushed the cinematographer to extremes to capture sharp images of character's faces amidst the deepest of sinister shadows. It's a world wherein occasionally the only thing visible were lanterns, or a few facial elements leaning into candlelight, almost like disembodied spirits.

Shura is based on the play Kamikakete sango taisetsu by Nanboku Tsuruya (1755-1829), whose most famous kabuki play is the often filmed Yotsuya Ghost Story. Shura though not quite as overtly supernatural as Yotsuya Ghost Story is nevertheless powerfully infused with a sense of demonic posession.

The screen adaptation was written & directed by Toshio Matsumoto. Matsumoto was an experimental filmmaker & some of his avant gardism finds its way into Shura but not so much that it seems to leave the samurai adventure genre.

A typical experimental treatment is when Gengobe breaks into the room where Koman is being sold to a patron & stops the transaction by redeeming her himself. But then he snaps to from this fantasized event & runs into the room to stop the transaction a little differently than imagined. Throughout there are odd little tricks played so that the line between reality, imagination, & nightmare blends.

Matsumoto is also a well known artist & photographer in Japan, & his pictorial sensibilities are all over this visually gorgeous, if horrifying, film.

Be warned there are SPOILERS AHEAD in this close look at a doomful story. The no-spoilers version would be simply, "This is a great movie, see if it you get the chance!"

Be warned there are SPOILERS AHEAD in this close look at a doomful story. The no-spoilers version would be simply, "This is a great movie, see if it you get the chance!"

The protagonist Gengobe Satsuma is played by Katsuo Nakamura. Katsuo is best known in the west for his role as Hoichi the Earless in Masaki Kobayashi's stunningly beautiful Kwaidan (1964). He is the brother of the late great Kinnosuke (Nakamura) Yorozuya, & is just about as superb on the screen as was his older brother, but with a strikingly natural sweetness about him which makes his monstrous decline in Shura all the more unsettling.

As the film artfully mixes dreams with waking events with imagination & finally with madness, reality is only a shifting perception. Only the feelings of loss & horror & sadness are certainly real.

Gengobe, though himself a poor ronin, has sold piece by piece everything he owns, save only for his sword, & taken on further debt in order to support a "country concubine" or low-grade geisha named Komon (Yasuko Sanjo). On the surface, Komon seems genuinely devoted to Gengobe, but as she herself admits, "A geisha's life is lies."

Gengobe had once been a retainer with the Asano clan. He keeps secret even from Komon that he is actually Soemon Fuekara, cast out from his clan due to financial irresponsibility. The clan was since dissolved by the shogunate, for reasons so void of reasonableness that the bravest of the clan's retainers were plotting an act of revenge that would be like a slap in the face to the shogunate. Gengobe had once been a retainer with the Asano clan. He keeps secret even from Komon that he is actually Soemon Fuekara, cast out from his clan due to financial irresponsibility. The clan was since dissolved by the shogunate, for reasons so void of reasonableness that the bravest of the clan's retainers were plotting an act of revenge that would be like a slap in the face to the shogunate.

If Gengobe/Soemon could only clear his old debt, he could have been, with clean slate, the 48th ronin among those who have come down to us through history as "The Brave 47."

A group of farmers & poor merchants who loved the wronged Lord have raised the money Gengobe requires, at great sacrifice to themselves, so that he would be able to join the others in the brave act. The funds are brought to him by an aging & devoted vassal, Hachiemon (Masao Imafuku), who begs him to repent of his wastrel existence with Komon, pay his neglected debts, & join the Brave 47 Ronin in their pursuit of a just revenge.

Moved to shame, Gengobe swears to do exactly as honor requires. But Komon, who had been gone most of that evening entertaining a client, happened to return home for a moment & caught a glimpse of the money. She leaves with pretense of not having seen a thing.

Soon Komon's pimp Sangoro (Juro Kara) arrives to warn Gengobe that one of Komon's clients is at that moment attempting to buy out her contract to make her his private mistress.

Soon Komon's pimp Sangoro (Juro Kara) arrives to warn Gengobe that one of Komon's clients is at that moment attempting to buy out her contract to make her his private mistress.

Gengobe is at risk of never seeing her again! He follows Sengoro along dark streets & then peers into a peep-hole made in a rice-paper window. He watches a tableau, as on a stage, which his naivete convinces him is in no way put on for his benefit, believing Komon couldn't possibly know he is spying on that room.

Several people are trying to convince Komon to let her client buy her contract. He promises her a luxurious life. It is obviously to her advantage not to have to do work as an indentured geisha. Everyone knows of her affair with the poor ronin & disapprove of him, for he has nothing to offer her. She declares that she loves Gengobe & would rather kill herself than live without him.

Eventually Gengobei bursts onto the scene & after great to-do tosses down the money that had been raised for him by others. He knows he is throwing away his destiny, but the chance to take Komon as his wife is worth the loss of all other things. Eventually Gengobei bursts onto the scene & after great to-do tosses down the money that had been raised for him by others. He knows he is throwing away his destiny, but the chance to take Komon as his wife is worth the loss of all other things.

But after his money is gone, & he stands prepared to marry her that very night, it is revealed that Komon is already married. In fact she is married to her pimp Sangoro, & they have a child together, which Gengobe had known nothing about. Realizing too late his naivete, Gengobei has lost both his destiny & his illusion of love.

Later that night he creeps back into the residence & in the abject darkness finds Komon in bed with Sangoro. He kills them both, along with others of the household. His acts of murder come off much closer to psychotic than the act of a samurai.

Due to the depth of the night, the foul deed is already done before he realizes he has actually killed only Komon's confederates. He doesn't regret the error since they were part of the ploy to defraud him & it was his plan to kill everyone involved. But the two primary objects of his revenge have escaped.

All this has happened in a single night. The rest of the film takes place some while later, on another & similar night. We never see dawn break in this film.

The film is slowly paced & it does not have a lot of violence in terms of percentage of screen time, though what violence it does have is extreme & appalling & unheroic to the highest degree.

This refusal to glorify violence has a distinct morality such as is missing from the common attitude of all sorts of filmic genres that assume killing is fun, revenge is good, & capacity for murder is manly & healthy. But the present film's vaster morality was completely misunderstood by the British censors who banned Shura in the UK. This refusal to glorify violence has a distinct morality such as is missing from the common attitude of all sorts of filmic genres that assume killing is fun, revenge is good, & capacity for murder is manly & healthy. But the present film's vaster morality was completely misunderstood by the British censors who banned Shura in the UK.

Gengobei, now again living as Soemon, is staying at a temple run by Priest Tokuemon. By a shocking set of coincidences unknown to Soemon, Tokuemon's son is Sangoro, his daughter-in-law is Komon. They have left the world of the sex trade, reclaimed their infant child, & are trying to get their lives back on a decent track.

The money they took from Komon's ronin lover, however, was not used for their own benefit, but was turned over to Sangoro's father, who in turn intended to use it to clear Soemon's debt. They have all secretly been supporters of the cause of the 47 Ronin!

Everyone in the tale stands balanced at a point where a just outcome for everyone seems possible. Alas, Soemon knows nothing of these connections. Although Komon knows she defrauded Gengobe to help a ronin named Soemon, she never knew they were the same man; & all "Gengobe" ever saw was that he was defrauded by a couple of thieves that preyed upon his naivete & emotions without regard for his ruin.

Terrible, terrible misery & death is what will be experienced instead of the just outcome that was a hair's breadth from occurring. Priest Tokuemon too late reveals to Soemon that he will be able to join the 47 ronin, because of the efforts of Komon & Sangoro. But by then, Soemon has already murdered Komon by a method of extreme horror, after first forcing her to grasp his sword as he murdered her infant.

Soemon sinking into the worst despairing guilt exclaims, "I no longer have the right or desire to be one of the faithful retainers." Realizing his demonic acts of that very night had no just basis whatsoever, he breaks down & confesses all that he has done, to Tokuemon's horror.

This whole while, Sangoro had been hiding nearby in a barrel-coffin for fear of being found by Gengobe. He has overheard that Gengobei is Soemon, who has killed Sangoro's wife & child. When Sangoro stands from the coffin, he is himself transformed into a hideous ghostly thing so lacking in desire to live that nothing remains but to kill himself.

The twists of horror have been many, ironic, & always very cruel. Last of all, Sangoro disembowels himself, having asserted, "This maggot can dwell only in the darkest place!"

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

But nowadays the film tends to be given simply as Shura & I like that best. But it has also been distributed as Pandemonium which is a lousy title; as Bloodshed which is awfully generic for a samurai film; & as Demons which is finally correct, the term Shura being derived from asura, a sanskrit buddhist/hindu name for a demon.

But nowadays the film tends to be given simply as Shura & I like that best. But it has also been distributed as Pandemonium which is a lousy title; as Bloodshed which is awfully generic for a samurai film; & as Demons which is finally correct, the term Shura being derived from asura, a sanskrit buddhist/hindu name for a demon. Washing the color out of the opening scene is like "announcing" this is a cruel tale, & the director pushed the cinematographer to extremes to capture sharp images of character's faces amidst the deepest of sinister shadows. It's a world wherein occasionally the only thing visible were lanterns, or a few facial elements leaning into candlelight, almost like disembodied spirits.

Washing the color out of the opening scene is like "announcing" this is a cruel tale, & the director pushed the cinematographer to extremes to capture sharp images of character's faces amidst the deepest of sinister shadows. It's a world wherein occasionally the only thing visible were lanterns, or a few facial elements leaning into candlelight, almost like disembodied spirits.

Gengobe had once been a retainer with the Asano clan. He keeps secret even from Komon that he is actually Soemon Fuekara, cast out from his clan due to financial irresponsibility. The clan was since dissolved by the shogunate, for reasons so void of reasonableness that the bravest of the clan's retainers were plotting an act of revenge that would be like a slap in the face to the shogunate.

Gengobe had once been a retainer with the Asano clan. He keeps secret even from Komon that he is actually Soemon Fuekara, cast out from his clan due to financial irresponsibility. The clan was since dissolved by the shogunate, for reasons so void of reasonableness that the bravest of the clan's retainers were plotting an act of revenge that would be like a slap in the face to the shogunate.

Eventually Gengobei bursts onto the scene & after great to-do tosses down the money that had been raised for him by others. He knows he is throwing away his destiny, but the chance to take Komon as his wife is worth the loss of all other things.

Eventually Gengobei bursts onto the scene & after great to-do tosses down the money that had been raised for him by others. He knows he is throwing away his destiny, but the chance to take Komon as his wife is worth the loss of all other things. This refusal to glorify violence has a distinct morality such as is missing from the common attitude of all sorts of filmic genres that assume killing is fun, revenge is good, & capacity for murder is manly & healthy. But the present film's vaster morality was completely misunderstood by the British censors who banned Shura in the UK.

This refusal to glorify violence has a distinct morality such as is missing from the common attitude of all sorts of filmic genres that assume killing is fun, revenge is good, & capacity for murder is manly & healthy. But the present film's vaster morality was completely misunderstood by the British censors who banned Shura in the UK.