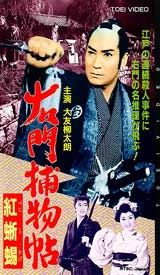

In the "samurai detective" movie Whirling Spider (Umon torimonocho: Manji gumo, 1962), an Edo constable, Umon Kondo, looks into the case of a ronin unjustly accused of murder.

The ronin is pursued by a second constable, Umon's inept rival Murakami, & his baffoon sidekick, who only want to prove the ronin guilty. But our hero detective, played by Ryutaro Otomo, knows the ronin is innocent & eventually will fight the bad-guys at the ronin's side.

The beautifully photographed black & white film sparkles with naive innocence, a happy film with a happy conclusion, typical of the samurai detective adventures produced by Toei Studios during this time. Viewers who have the impression of Japanese cinema as intense, gloomy, & tending to unhappy endings have missed the "B" films which are upbeat family entertainment.

A western viewer might suspect this film is a hybridization of the west's idea of a detective story & a Japanese samurai film. In actuallity the samurai detective story originated in the Tokugawa Period with Tales of Japanese Justice by Ihara Saikaku (1642-1693). Saikaku's mystery short stories told of the clever detective work of leading Edo magistrates famed for upholding justice & arriving at fair judgements.

So films like Whirling Spider are a continuation of a very old & traditional method of storytelling. And the western assumption that detective fiction begins with Edgar Allen Poe immediately before the Victorian Age, if such could be credited, would mean that Japanese detective fiction reached a high level of sophistication centuries before short story art matured in the west.

The climactic swordfight in Whirling Spider is rapidly choreographed & lengthy. Some of these Toei family films are bloodless, but in this protracted massive duel, the key villains do get killed. Still, the violence never seems more than the grand fun of movie-pretense. The lives of the magistrate & the ronin are never threatened & the blood of the deserving dead is practically invisible.

Continuing in a vein of comedy which is a major attribute of the Detective Umon series, the audience is treated to numerous sight-gags in Woman with an Umbrella (Umon Torimoncho: Jyanomegasa no onna, 1963).

For example, Umon's career rival, Murakami, who never knows how silly he is, happens to have freckles across his nose. When we see Murakami's two children in an early scene, the little squirts have the exact same freckles. And during the misadventures of Umon's sidekick Den, the comedy relief is typified by a scene wherein Den is trying to gather useful information but everybody pretends to be deaf so they won't have to talk to him.

Ryutaro Otomo as the Edo magistrate Umon Kondo is out to solve a crime that centers around the murder of a jail guard & the escape of a criminal who is later himself killed. His dying words in Umon's arms were, "I didn't kill the guard."

The murdered criminal had been a safe-cracker & only his girlfriend knows where he hid a fortune (at the bottom of a pond). She is kidnapped, so the plot gets thicker & thicker.

Above Umon & Murakami is their kindly senior, Kakurai, who we slowly begin to suspect of having had something to do with the criminal happenings. The non-stop comedy of the bulk of the film actually runs out shortly before the ending, when Kakurai's motives for turning into a bad cop are unveiled. Kakurai had been such a kind man we sympathize with him more than a murderer deserves. Umon has sympathy, too, & promises to report that Kakurai died nobly in the line of duty, if he will commit seppuku at once.

Kakurai instead attacks Umon & for the first time in the whole film, Umon draws his sword. He kills his senior & tells the other constables a few moments later, "After he fulfilled his duty -- he died." Only Umon & his tearful sidekick Den know the truth, but justice is no less restored.

Samurai detective yarns are rarely serious films & even though few are as overtly comical as magistrate Umon films, they are never severe or nihilistic like the best adult jidaigeki historical swordplay films. Lighthearted tales of samurai detectives series were especially common during the 1950s samurai film revival, & continued into the mid-1960s as a subgenre of their own, but thereafter moved to episodic television.

Though such films are suitable for children, they do interest adult viewers, as they tend to have a sophisticated level of acting despite lightweight plots. The stars, including Ryutaro Otomo, were often middle-aged or older gents who'd been matinee idols from the silent era to the 1940s. Though such films are suitable for children, they do interest adult viewers, as they tend to have a sophisticated level of acting despite lightweight plots. The stars, including Ryutaro Otomo, were often middle-aged or older gents who'd been matinee idols from the silent era to the 1940s.

During the Occupation, swordplay films were banned by McArthur due to the supposed military spirit of all chambara or jidaigeki (though in fact many such films were no more militaristic than a cowboy film in the west). When Japan was back in control of its own affairs, samurai films returned with a vengeance, & actors like Otomo or Chiezo Kataoka who'd been big jidaigeki stars before & during the war returned for a second wind in their careers. By now mature actors, they have a definite adult appeal.

The martial arts action in the Umon series is not generally graphic. In the final battle sequence of Woman with an Umbrella, Umon fights with a jitte, a defensive women which is also the equivalent of a lawman's badge. It's surprising more films don't focus a bit on jitte action, as it's a forked weapon that can stop a sword, & with the right twist can even break a sword. In the right hands it can render a swordsman helpless.

There are other scenes of action, but the greater focus is on uncovering the clues, in a manner that allows for the viewer to solve the crime even before Umon explains everything near the end.

The other focus, of course, is comedy. Even so, there are serious moments, & post-climax codas aren't invariably entirely happy. In Whirling Spider the final carnage brings death to all the criminals, but it is staged in such a way as to be a pretty strightforward "Isn't Justice Fun" battle. But in Woman with an Umbrella, good guys & good gals as well as bad ones have died along the way, & a man who had formerly been good becomes corrupted; so the final resolution retains an air of tragedy. The other focus, of course, is comedy. Even so, there are serious moments, & post-climax codas aren't invariably entirely happy. In Whirling Spider the final carnage brings death to all the criminals, but it is staged in such a way as to be a pretty strightforward "Isn't Justice Fun" battle. But in Woman with an Umbrella, good guys & good gals as well as bad ones have died along the way, & a man who had formerly been good becomes corrupted; so the final resolution retains an air of tragedy.

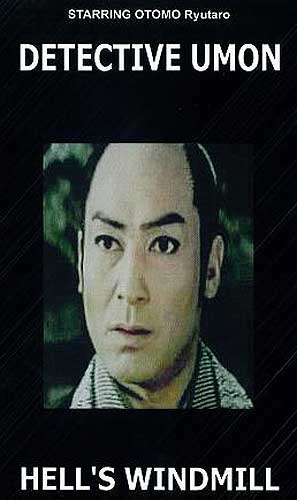

Otomo played Umon Kondo several times, including in Tadashi Sawashima's Hell's Windmill (Umon Torimonocho: Jigoku no kazaku-ruma, 1960). In this adventure, he must clear falsely charged individuals of murder before his rival magistrate Keishiro destroys innocent lives. Otomo played Umon Kondo several times, including in Tadashi Sawashima's Hell's Windmill (Umon Torimonocho: Jigoku no kazaku-ruma, 1960). In this adventure, he must clear falsely charged individuals of murder before his rival magistrate Keishiro destroys innocent lives.

In the same director's The One-eyed Wolf (Umon torimonocho: Katame no okami, 1959) Umon has to track down the titular assassin known as the One-Eyed Wolf while solving the mystery of the bowstring murders.

Although Otomo became strongly identified with the Umon Kondo role (probably only his recurring role as the folk figure of Tange Sazen was more popular among his performances), he was scarsely the first to play the character.

An important silent film survives, Kumahiko Nishina's Umon torimonocho rokuban tegara jinenji kidan (The Samurai Detective, aka The Detective Records of Umon, aka Detective Umon Diary: Exploit Number Six, 1930). Umon on his shining white horse stops a conspiracy against the Shogun. Umon was played by Kanjuro Arashi in this early film, & long after in the post-Occupation jidaigeki revival he reprised the role in Kajiro Yamamoto's Muttsuri Umon torimonocho (1955), helping to launch the renewed interest in such films.

Chiezo Kataoka played Umon Kondo in another early version which survives, Tsuji Yoshiro's Umon torimonocho: sanjuban tegara (The Casebook of Umon: His Third Achievement, 1932). Chiezo, like Otomo, played similar samurai detective characters during the post-occuptation jidaigeki rivival, & one of his best-known detective characters was "the tattooed cherry blossom judge."

One factor in most of the samurai detective series is not much reflected in Otomo's Detective Umon films. Because stars like Ryutaro Otomo & Chiezo Kataoka lacked youth appeal, it was typical to have a handsome young newcomer as second lead. At Toei Studios, Ryutaro & Chiezo commonly co-starred in samurai detective films with youthful Hashizo Okawa or Kinnosuke Nakamura. See the reviews of Mito Komon & Three Young Rebels for examples of youth with senior casting in the samurai detective genre.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

Though such films are suitable for children, they do interest adult viewers, as they tend to have a sophisticated level of acting despite lightweight plots. The stars, including Ryutaro Otomo, were often middle-aged or older gents who'd been matinee idols from the silent era to the 1940s.

Though such films are suitable for children, they do interest adult viewers, as they tend to have a sophisticated level of acting despite lightweight plots. The stars, including Ryutaro Otomo, were often middle-aged or older gents who'd been matinee idols from the silent era to the 1940s. The other focus, of course, is comedy. Even so, there are serious moments, & post-climax codas aren't invariably entirely happy. In Whirling Spider the final carnage brings death to all the criminals, but it is staged in such a way as to be a pretty strightforward "Isn't Justice Fun" battle. But in Woman with an Umbrella, good guys & good gals as well as bad ones have died along the way, & a man who had formerly been good becomes corrupted; so the final resolution retains an air of tragedy.

The other focus, of course, is comedy. Even so, there are serious moments, & post-climax codas aren't invariably entirely happy. In Whirling Spider the final carnage brings death to all the criminals, but it is staged in such a way as to be a pretty strightforward "Isn't Justice Fun" battle. But in Woman with an Umbrella, good guys & good gals as well as bad ones have died along the way, & a man who had formerly been good becomes corrupted; so the final resolution retains an air of tragedy.