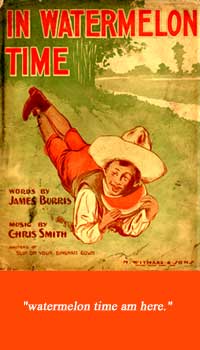

A song by James Burris & Chris Smith published in 1909 was called "In Watermelon Time" which begins illterately, "Watermelon time am here." It's not really a song about race; it's about getting married when it's time to harvest watermelons. A song by James Burris & Chris Smith published in 1909 was called "In Watermelon Time" which begins illterately, "Watermelon time am here." It's not really a song about race; it's about getting married when it's time to harvest watermelons.

And yet the painting on the cover of the sheet music assumes a young black man is the watermelon-chomper of the song (I reproduce that picture above; in it's favor, it's not an awful caricature, he's just a handsome young black guy).

Why were watermelons so strongly identified, in white minds, with black folk? I grew up eatin' 'em, & I ain't black. The reason chitlins' & pig's feet became soul food to the black community is because it was the cheap food or the garbage that was fed to slaves. Were watermelons part of that legacy?

It's also speculated that watermelons came to the Americas in the 17th Century together with slave ships, as water & food for the cargo. I doubt that theory since watermelons had been in the Americas since the 1500s, probably brought by free black Berbers who worked as sailors from the earliest days of European contact.

What I find plausible is that North American whites didn't know how to grow watermelons but their slaves did, & far from being "lazy darkies" they gardened so their enslaved families could eat better than some s.o.b. "master" would feed them, & their choices would be crops from Africa. Whites instead of thanking anybody for teaching us how it's done just made caricatures out of it.

From the very beginnings of the history of motion pictures, this stereotype has been present. It's too bad that issues of race are such that the mere act of showing black guys devouring watermelons at full tilt comes off as racist humor. It should just be people eating watermelon, since that's why we grow them for crine out loud.

The Watermelon Contest; aka, Watermelon Eating Contest (1896) from the Edison Manufacturing Company seems to have been the first of what would become a veritable genre of short-short films showing black people eating watermelons. It shows two happy watermelon-chomping fellows racing to finish their cooling treat & spitting seeds. The Watermelon Contest; aka, Watermelon Eating Contest (1896) from the Edison Manufacturing Company seems to have been the first of what would become a veritable genre of short-short films showing black people eating watermelons. It shows two happy watermelon-chomping fellows racing to finish their cooling treat & spitting seeds.

In its day it was categorized as "an expression film" as it was about mugging to the camera. Facial expression films were not about race, & it really looks as though the whites who concocted such films never even thought about the aspect of racial stereotyping in this film. It just popped out of the young film industry naturally, without thinking.

Soon after the first Watermelon Eating Contest film proved to be a hit, there was Watermelon Feast (1896) from American Mutoscope showing a black family eating what the Mutoscope film catalog described as "the favorite food of their race."

It's hard to believe audiences loved the topic of these mini-films so much. When so many copies of Watermelon Easting Contest had been struck that the original negative wore out by 1900, the Edison company remade it as Watermelon Contest (1900), extending it to well over a minute, & adding a few nuances of the four contestants interfering with one another. The four guys are poking & grabbing each others melons, knocking a hat off, spitting seeds, & making themselves laugh.

Then New Watermelon Contest (1903) was filmed by Lubin in order to horn in on the "classic's" profits, though some old records suggest Lubin actually made it in the wake of the first Edison Company version as New Watermelon Contest (1897). Lubin also made Eating Watermelon for a Prize (1903) which was more of a free-for-all of black men eating, fighting, & washing with watermelons.

Lubin also made Who Said Watermelon? (1902) in which women get to be the ravenous devourers of the lucious fruit, & the Lubin catalog noted that they'd made this one in order to meet the public's demand for just this theme.

Then Selig Polyscope Company wanted in on the bonanza &, with Who Said Watermelon? (1903) about an old black man who has obtained a large watermelon & is set upon by black urchins eager to steal it, with funny-sad results for everyone.

Selig like the other early film studios made lots of films with black casts, & it's just too damned bad these couldn't've been realistic moments in African American history rather than comedy antics designed to fulfill a narrow white expectation of black behavior.

Although, to be sure, Selig was deeply familiar with minstrel shows, having formerly been a magician & minstrel show manager, & some of the stereotypes caught on film were promulgated by black performers themselves.

This is perhaps why his Who Said Watermelon? honestly comes of as a "bad boys" film which were almost always about young white troublemakers. There's no intimation here that the attempted thievery was because of blackness, but only because boys will be boys.

All too many of the "watermelon" films wouldn't work for white folks if they'd been about white folks, as the humor for some gawdforsaken reason was the fact that it was black folks eating them. But with Selig's Who Said Watermelon? it's easy to see that the same story would have been just as effective regardless of race.

Not all these films survive but they are well-documented in contemporary catalogs, a great many more than mentioned here. I've cited only those stereotyping films that feature watermelons. The examples that are presently easy to find in circulation are the two James H. White "contests" & The Edwin S. Porter discussed below.

More alarming (& revealing) than these simpleminded images of race stereotypes is the one-reel ten-minute The Watermelon Patch (1905) which by its greater substance manages to pack in more than just the awful stereotypes.

More alarming (& revealing) than these simpleminded images of race stereotypes is the one-reel ten-minute The Watermelon Patch (1905) which by its greater substance manages to pack in more than just the awful stereotypes.

The creators of this film, Edwin S. Porter & Wallace McCutcheon, who were among the best the kinetoscopic era.

In its favor, The Watermelon Patch tells a full story rather than just a scene. The black actors also put their hearts into their roles & are sufficiently talented I have to assume they were hired from a chitlin circuit vaudeville company.

Alas, while it's supposed to be a comedy, & has some quaintly amusing bits, before it's over it is much more wholly about race hatred.

Rural black guys are crawling around on their hands & knees in the watermelon patch, stealing watermelons from the white farmer.

The two scarecrows turn out to be white guys who've sprung a trap. They throw off their scarecrow garments & reveal their "skeleton bones" outfits. Negroes being childlike & naive, they run off convinced these are real spooks. The two scarecrows turn out to be white guys who've sprung a trap. They throw off their scarecrow garments & reveal their "skeleton bones" outfits. Negroes being childlike & naive, they run off convinced these are real spooks.

An extended chase scene has the skeletons chang the black men through woodlands, cornfields, & country roads, but eventually the watermelon thieves escape from the skeletons.

The family back home is dancing up a storm to banjo music. Some of the dances are pretty darned good, played for laughs. Suddenly one of the watermelon thieves shows up & soon everyone's eating watermelon.

Incorporated into the eating scenes is a veritable remake of the original facial expression-film, Watermelon Eating Contest, of two guys seated side by side making faces while rapidly eating their slices of melon.

Meanwhile a group of white vigilantes with their hounds are tracking the thieves back to their cabin, which they immediately nail closed & seal up all the windows. Meanwhile a group of white vigilantes with their hounds are tracking the thieves back to their cabin, which they immediately nail closed & seal up all the windows.

The rednecks begin to seal up the windows & doors & even plug the chimney. If they were the Klan they'd've set fire to the place, but this is supposed to be "funny" so the only thing that happens is the people in the cabin nearly die of affixiation.

Porter almost acknowledges the horror of the event where he cuts to an interior shot of the trapped family listening to the whites boarding up their cabin. But in the main it's played for laughs. What a shame this "land of the free" has had, & continues to have, such a legacy of hate that this could ever have been regarded funny by anyone at all.

It's only an assumption the eager audience for multiple films on the topic of black folks gobbling down watermelons were just about exclusively white folks.

If that assumption is true, then the question would be, what on earth was so interesting about it? The theme was also popular for post cards & fruit labels. Did whites never notice their own race also liked to gobble down watermelons? If that assumption is true, then the question would be, what on earth was so interesting about it? The theme was also popular for post cards & fruit labels. Did whites never notice their own race also liked to gobble down watermelons?

It's not impossible, however, that these films were additionally popular in kinescope parlors that served a black clientelle. If it were the only way of seeing oneself represented, it'd have to do, & it was true that black comics on the chitlin circut did similar kinds of humor, which naturally took on a different meaning done black for black.

These films are important for showing the beginnings of cinematic portraits of black America, & show that at the very beginning of the movie industry blacks were present, however imperfectly represented. By the mid teens America would have its first black filmmaker & film star with Bert Williams who wrote, directed & starred in three short films for Biograph, of which Natural Born Gambler (1916) survives.

By 1919 Oscar Micheaux arose as the "first black film impressario," The Homesteader (1919) the first full-length feature film written & directed by a black American. When blacks were at the helm we got such films as Micheaux's Body & Soul (1925) in which a white woman (Marcedes Gilbert) falls in love with & wants to marry a black man (Paul Robeson).

With whites dominating the industry, the biggest black film stars ended up being character players like Lincoln Perry billed always as Stepin Fetchit the ultimate slow-witted slow-talking slow-shuffling shiftless eye-rollin' ske'ert darkie.

Although Perry is overly maligned for this character. Stepin Fetchit never got round to fetching anything for anyone not because he was lazy & shiftless & stupid but because he was a subversive trickster who managed never to serve the oppressor.

That, at least, is what was perceived by black audiences who'd often seen such characters portrayed in all-black minstrel shows, & probably seen it played for real when some commanding "massah" was trying to get unpaid labor out of someone. But it's true such characters inevitably meant something else when presented by white directors to predominantly whlite audiences.

It's a long way from there to today's superstars like Denzel Washington & Wesley Snipes, but it did all begin with those "facial expression films" of black folks eating watermelons.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|

The Watermelon Contest; aka, Watermelon Eating Contest (1896) from the Edison Manufacturing Company seems to have been the first of what would become a veritable genre of short-short films showing black people eating watermelons. It shows two happy watermelon-chomping fellows racing to finish their cooling treat & spitting seeds.

The Watermelon Contest; aka, Watermelon Eating Contest (1896) from the Edison Manufacturing Company seems to have been the first of what would become a veritable genre of short-short films showing black people eating watermelons. It shows two happy watermelon-chomping fellows racing to finish their cooling treat & spitting seeds.

The two scarecrows turn out to be white guys who've sprung a trap. They throw off their scarecrow garments & reveal their "skeleton bones" outfits. Negroes being childlike & naive, they run off convinced these are real spooks.

The two scarecrows turn out to be white guys who've sprung a trap. They throw off their scarecrow garments & reveal their "skeleton bones" outfits. Negroes being childlike & naive, they run off convinced these are real spooks. Meanwhile a group of white vigilantes with their hounds are tracking the thieves back to their cabin, which they immediately nail closed & seal up all the windows.

Meanwhile a group of white vigilantes with their hounds are tracking the thieves back to their cabin, which they immediately nail closed & seal up all the windows. If that assumption is true, then the question would be, what on earth was so interesting about it? The theme was also popular for post cards & fruit labels. Did whites never notice their own race also liked to gobble down watermelons?

If that assumption is true, then the question would be, what on earth was so interesting about it? The theme was also popular for post cards & fruit labels. Did whites never notice their own race also liked to gobble down watermelons?