"The only 'ism' Hollywood believes in is plagiarism."

-Dorothy Parker

Big Fat Liar (2000) is a light comedy featuring child actor Frankie Muniz as a fourteen year old writer whose work is plagiarised by a film director (Paul Giamatti) who is confident nobody will ever believe his script originated with a child. The kid, however, is not taking the theft lying down. Adult & child spend most of the movie in a slapstick battle of wit & will, culminating in the crooked director's professional annihilation & the child's full screen credit.

Big Fat Liar is not-so-secretly a Hollywood in-joke about how Hollywood actually works. In the real world of the film industry, moguls just about never get punished for their crimes. Little guys are robbed left & right & are helpless against injustice. So Big Fat Liar is something of a fantasy of what might happen if justice were possible. And even in the fantasy version, what it takes is extreme measures.

Because ideas cannot be copyrighted, to steal ideas skirts along the possibility of legality. If a director or producer reads someone's script, rejects it out of hand perhaps even pretending never to have read it, & then sets out to write another script just like it, proving that the two scripts full of cinematic cliches have a common origin might not be enough to establish a breach of copyright laws.

And this happens all the time. Steven Spielberg is one of the most notorious practitioners of the fine art of taking credit where credit is not due (see the article on Amistad, Steven Spielberg, & Plagiarism).

Spielberg is not an exception in an otherwise honest sphere. He's merely the power-man, the trend-setter. Here are a handful of examples of what Big Fat Liar is on about in the world of Hollywood plagiarism:

In an industry obsessed with remakes & sequels & spinoffs & movie versions of old tv shows, originality is never expected, & the line between "influence or adaptation" vs outright plagiarism is often only a matter of who got paid & who got screwed out of being paid.

Either way the the film will not be particularly original, & the way films steal from each other is sometimes so obvious you'd think they were proud of it. The Screenwriter's Guild has elaborate rules for who gets the writing credits -- & within the rules, there is often only a tangential relationship between screen credit & the actual originator or majority author of a script.

The actual authors of original screenplays or of works of fiction from which screenplays take all their key points, or other original works whose creators don't get paid or credited, never feel that these thefts are cinematic homages as when Lucas swipes images from nazi propoganda films to make Star Wars look cool. No, the authors would rather get credit and money, though they'll very often settle for just the money if they can get even that. The actual authors of original screenplays or of works of fiction from which screenplays take all their key points, or other original works whose creators don't get paid or credited, never feel that these thefts are cinematic homages as when Lucas swipes images from nazi propoganda films to make Star Wars look cool. No, the authors would rather get credit and money, though they'll very often settle for just the money if they can get even that.

One of the side-features of plagiarism in Hollywood is the manner by which two films of identical theme can appear simultaneously. Some directors work under strict secrecy knowing that a duplicate film could be rushed into production by someone hoping to coattail on the advertising of the original, but tending to dilute the boxoffice of either film. Sometimes it turns out that a pair of films did not imitate each other, but do have a common uncredited source as their origin.

A case in point is Volcano & Dante's Peak both released in 1997 (Twister & Tornado! both from 1996 would be similar examples). A case in point is Volcano & Dante's Peak both released in 1997 (Twister & Tornado! both from 1996 would be similar examples).

The two volcano films are widely said to have had their origin in a script called Magma Town by Hollywood outsider Aleksandar Skocajic. He began making the rounds in Hollywood in 1994. One year later nearly identical scripts by Hollywood insiders for Volcano and Dante's Peak were sold to Fox & Universal respectively.

These two films also provide a case study of how difficult it is to prove in court that plagiarism exists if the idea for the film was essentially stupid & cliche. Close comparisons of all three scripts found 250 scenes are identical between Magma Town & Volcano. A less astounding 80 scenes are identical between Magma Town & Dante's Peak. The plagiarism is self-evident, but the obviousness of it won't easily meet a legal burden.

Therefore this would appear to any attorney to be a difficult case, lacking a direct paper trail to the credited authors of the filmed scripts. Therefore this would appear to any attorney to be a difficult case, lacking a direct paper trail to the credited authors of the filmed scripts.

The usual argument of "coincidence" could easily hold up in court, despite that Skocajic was almost certainly copied by readers of his script, which was a little inept because English was not his first language.

And from the Hollywood point of view, who expected a car mechanic in far away Serbia to be able to do anything about the theft. Skocajic's monthly salary was $300, & there was no chance in hell that he could afford even one day of an attorney's time.

An attorney would not be likely to take on a costly case that was difficult to win, unless he were paid up front. Or -- unless the robbed author was an attorney! To whit:

Marie Flaherty, a New York attorney, had been shopping around her screenplay Amoral Dilemma, about the repurcussions of an attorney starting an on-line relationship with a criminal serving time.

Flaherty had the assistance of fellow attorney George N. Tobia & his friend Jason Filardi who claimed to have Hollywood connectons Flaherty lacked. But when Amoral Dilemma made it to the screen starring Queen Latifah & Steve Martin, it was retitled Bringing Down the House (2003) & the author credit went to Tibia & Filardi. Flaherty sued.

It is possible that occasionally the plagiarisms are unintentional when young directors & screenwriters take an idea from someone else & naively believe they turned it into something original, or maybe even forgot that they read that story when they were young science fiction nerds. It is possible that occasionally the plagiarisms are unintentional when young directors & screenwriters take an idea from someone else & naively believe they turned it into something original, or maybe even forgot that they read that story when they were young science fiction nerds.

A case in point would be James Cameron's plagiarism of a story written by Harlan Ellison & adapted by the author as an episode Outer Limits called Soldier (1964), & which Cameron transmuted into the box-office giant The Terminator.

Now some Hollywood moguls when caught in such an error attempt to sue the original creator into bankruptcy (see for examples the companion article on Steven Spielberg & plaigiarism). But when done naively, it should be easy to make it right. Harlan won his court case hands-down. Not only was he belatedly paid a good chunk of change, but he was thereafter fully credited as the original source for the film.

But why was it even necessary to drag into court? Why didn't Cameron just do the right thing with big apologies for naivety? Well, as it turns out, the plagiarism that gave rise to The Terminator was only the first & most famous of Cameron busts, so perhaps we need another example of actual naivety:

Ridley Scott's Alien (1979) was not-so-secretly based on A. E. van Vogt's 1939 short story "Discord in Scarlet" which became part of his novel Voyage of the Space Beagle (1950). Van Vogt sued & quickly won an out of court settlement. I am willing to believe Ridley read that story at such a young age he completely forgot. But how can we ever know if the plagiarism was intentional or naive when so many filmmakers do it with intent?

The crappy film The Omego Code (1999) was plagiarised from Sylvia Fleener's doomsday novel The Omega Syndrome (1997), resulting in a 40 million dollar lawsuit, settled out of court with the proviso that Fleener never again speak publicly about the theft. The crappy film The Omego Code (1999) was plagiarised from Sylvia Fleener's doomsday novel The Omega Syndrome (1997), resulting in a 40 million dollar lawsuit, settled out of court with the proviso that Fleener never again speak publicly about the theft.

Getting the robbed authors to agree to be silenced is commonplace in these kinds of deals. But the filmmakers themselves remain free to continue to say the charge of plagiarism is "flat wrong" as often as they like, while Fleener agreed to be muzzled for a price.

The cutesy-poo working class striptease-boys film The Full Monty (1997) was plagiarized from a New Zealand play, Ladies Night (1987), by Andrew McCarten & Stephen Sinclair.

The producers launched an aggressive public campaign against McCarten & Sinclair. They made such outrageous false claims as the play being as much like the movie as The Beverly Hillbillies was like Gone with the Wind, & that nobody on earth ever saw that dumb play anyway.

So the authors responded by putting the play on-line so that people could see for themselves the similarities, which induced a settlement & the website was removed as part of that settlement. The authors have not spoken of it since, in another muzzling such as contributes to the ease with which works are misappropriated.

The Eddie Murphy vehicle Coming to America (1988) was plagiarized from a manuscript by syndicated columnist Art Buchwald. It took a four-year court case that most authors couldn't have hoped to launch, but Buchwald launched it, & won. The Eddie Murphy vehicle Coming to America (1988) was plagiarized from a manuscript by syndicated columnist Art Buchwald. It took a four-year court case that most authors couldn't have hoped to launch, but Buchwald launched it, & won.

The most repulsive comic ever to score a gig on Saturday Night Live claimed co-authorship of The Animal (2001), which was in reality based on an original screenplay called The Organ Donor, the authors of which having been promised a contract for their script a year before Rob Schneider appropriated the awful story as his own.

News about the suit was cut short, my guess is because the film was so trivial & there was probably an out of court settlement demanding the actual two writers keep their mouths shut forever more, as is frequently the case.

Toby Emmerich's screenplay for the scifi thriller Frequency (2000) turned out to be plagiarized from screenwriter Bill Selby's original script Doubletime.

There was a pretty good paper trail between the two scripts, despite intermediary rewriters before it was handed to Emmerich to rewrite yet again & get the screenplay credit while Selby got nothing. There was a pretty good paper trail between the two scripts, despite intermediary rewriters before it was handed to Emmerich to rewrite yet again & get the screenplay credit while Selby got nothing.

The judge in the case made it clear which side he was coming down on, so New Line hurried up & made a settlement offer complete with the usual non-disclosure agreement.

Emmerich gets to keep his faux credit & his career has continued. Note that it is normal to hire rewriters & often only the last rewriter gets screen credit, or some of these scripts would have ten authors; & thus the plagiarism was New Line's & not Emmerich's who was at least the second rewriter & was just doing a standard hack hireling's job & couldn't've known the original author had never been contracted or paid.

If they'd only paid Selby up front, none of it would be called plagiarism, though it still would not have been original to the credited people! This illustrates the slope that Hollywood's idea of "originality" slips down everyday, when even the "honestly gained" projects are purchased from one author & credited to another author, so no wonder authors get ripped off with cavalier abandon.

Robert Redford's The Sting (1973) was plagiarized from a 1941 nonfiction book, settled out of court in the actual author's favor.

The unintentionally creepy & not at all funny talking-baby film Look Whose Talking (1989) by Amy Heckerling was discovered to have been "borrowed" wholesale from a screenplay shown to her three years before she sold her version.

That too was quickly settled out of court in the author's favor. But injustices persist because there was a sequel for which the original author was not likely payed. The fact that Heckerling has gone on to sell many more film projects indicates how little Hollywood cares if they are dealing with a thief. Birds of a feather!

There's nothing at all new about this Hollywood habit of plagiarism. Val Lewton's evocative, frightening & beautifully filmed low budget thriller The Ghost Ship (1943) was put in a vault for 50 years because it was proven in court to have been plagiarized from a play of the same theme & title that had already been submitted to him by Samuel R. Golding & Norbert Faulkner. There's nothing at all new about this Hollywood habit of plagiarism. Val Lewton's evocative, frightening & beautifully filmed low budget thriller The Ghost Ship (1943) was put in a vault for 50 years because it was proven in court to have been plagiarized from a play of the same theme & title that had already been submitted to him by Samuel R. Golding & Norbert Faulkner.

And it just goes on & on. The mediocre Jennifer Lopez vehicle Enough (2002) issued by Sony Pictures was suspiciously similar to Allyson Turner's script Even Exchange which had been submitted to Sony well before a plagiarism began production.

Turner only became aware of the plagiarism after friends who had read her script began congratulating her after seeing Lopez's film. Sony was sued for five million dollars. Turner only became aware of the plagiarism after friends who had read her script began congratulating her after seeing Lopez's film. Sony was sued for five million dollars.

Or imagine his surprise when John Wrathall saw the Robin Williams vehicle One Hour Photo (2002) & immediately recognized that it was an extended version of his eight minute short subject Magic Moments (1996).

Wrathall's little film had played in film festivals world-wide & even had a theatrical release in England.

Wrathall said he was flattered to have been plagiarised, but would even so like to be paid for the adaptation rights now that the theft had come to light.

If it comes from a Hollywood outsider, a script is assumed to be worthless even if it is apt to be a commercial success. In an article published in 2001 by the Society of Authors, Leon Arden outlined how he sued & lost a fairly obvious case of plagiarism. If it comes from a Hollywood outsider, a script is assumed to be worthless even if it is apt to be a commercial success. In an article published in 2001 by the Society of Authors, Leon Arden outlined how he sued & lost a fairly obvious case of plagiarism.

He had submittted to Columbia Pictures for film adaptation his 1981 novel One Fine Day, about a man pursuing love while caught in a time loop. It was rejected, only to be plagiarised as the Bill Murray vehicle Groundhog Day (1993).

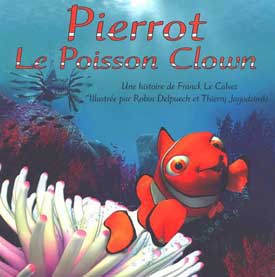

The endearing cartoon Finding Nemo (2003) was awfully well done by Disney, but it unfortunately "borrowed" rather too heavily from the French children's book Pierrot Le Poisson Clown (1995) by Pascal Kamina. The endearing cartoon Finding Nemo (2003) was awfully well done by Disney, but it unfortunately "borrowed" rather too heavily from the French children's book Pierrot Le Poisson Clown (1995) by Pascal Kamina.

The film's central character & supporting cast are the same as in the book, as are several plot elements. A screen treatment of the book had in fact been making the rounds of French film studios, & the connections between French production companies & Hollywood's are pretty greatly ingrained.

Even the art design for the characters was swiped. The picture of Pierrot at right shows that the character is identical to Nemo.

The 1960s tv series Lost in Space revamped as a movie many decades later was credited as the brainchild of Irwin Allen. But it had its uncredited origin in an Ib Melchior pilot script for the unproduced series Space Family Robinson. The scandal is documented in Edward Shifres non-fiction book Lost in Space: The True Story (1998).

Plagiarisms of soundtracks would be a whole additional essay, but here's a representative example. When Huey Lewis turned down the offer to write the themesong to Ghostbusters (1984), the job fell Ray Parker Jr., who "just happened" to write a theme that sounded exactly like "I Want A New Drug" by Huey Lewis & the News.

Obviously Parker had been instructed to copy the sound the filmmakers had been told by the source that they could not use. Lewis won his case, but his sound remains associated forevermore with Ghostbusters which Lewis had never wanted.

The examples could be cited ad infinitum, for theft is the bulwark upon which Hollywood is built.

copyright © by Paghat the Ratgirl

|